Concepts, Definitions and Measures

It is helpful to first think about what food security is.

The United Nations defines food security as when “all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their food preferences and dietary needs for an active and healthy life”.[i]

Household food insecurity is the inadequate or insecure access to food because of financial constraints.[ii] Food insecurity ranges from marginal to severe.

- Marginal food insecurity exists when households worry about running out of food and / or limit their food selection due to cost.

- Moderate food insecurity occurs when people compromise the quality and / or quantity of food consumed due to cost.

- Severe food insecurity occurs when people miss meals, reduce their food intake or, at the most extreme go for day(s) without food.

Recent Trends in Canada

- 6% of people living in the provinces experienced marginal, moderate, or severe food insecurity in 2019.[iii] This included 7.9% who were moderately food insecure and 3.6% who were severely food insecure.

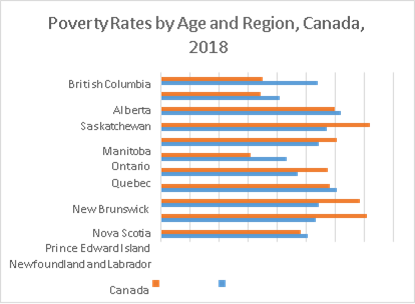

- Food insecurity is highest in the Territories. In 2017/18, almost half (49%) of all households in Nunavut experienced some level of food insecurity, followed by the Northwest Territories (15.9%) and the Yukon (12.6%). Among the provinces, Quebec reported the lowest rate of food insecurity rate (7.4%), and Nova Scotia the highest (10.9%).[iv]

- Although not a perfect indicator of food insecurity, reliance on emergency food assistance can indicate unmet food needs. Between 2019 and 2021, food bank visits in Canada increased by 20.3%, and March 2021 saw 1.3 million visits to food banks.[v]

Who is Food Insecure?

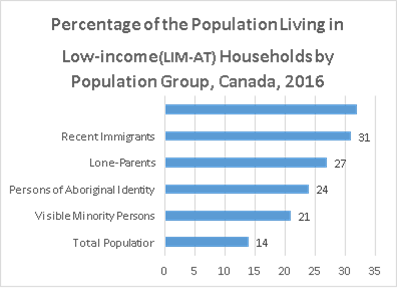

While food insecurity can affect anyone, certain population groups may be more at risk than others.

- In 2019, food insecurity rates were the lowest for persons in senior couples, and highest for persons in female lone-parent families. Single adults and lone-parent families also had a food insecurity rate higher than the national average.5

- Rates of food insecurity are high among post-secondary students, ranging from 42% in 2017[vi] to 57% in 2021.[vii] International students, Indigenous, Latinx, and Black students, 2SLGBTQ+ identifying students, as well as students experiencing precarious housing face a heightened vulnerability to food insecurity.vii

- Indigenous peoples, recent immigrants, and persons with a disability are more likely to face food insecurity; in 2019, the number of Indigenous people moderately or severely food insecure was more than double the overall population.5

- Most food insecure households are in the workforce, and they might be in low-wage jobs and precarious work conditions.

- Households experiencing food insecurity can be both renters and homeowners, though the rate of food insecurity is significantly higher among those living in rental accommodations.[viii]

While there is value in understanding who is more likely to experience food insecurity, it is important to avoid portraying social groups as inherently vulnerable.[ix] The underlying systems that make some people vulnerable must be addressed, such as the legacy of colonization, poverty, and systemic racism. People who experience food insecurity have important perspectives and insights and should be meaningfully included in decision-making processes.

Complex Causes of Food Insecurity

Income Levels

Food insecurity essentially stems from the ability of people to afford the food that they need.[x] Income levels impact food insecurity, including low-wage jobs and precarious work conditions. Insufficient social assistance benefits render households, especially single-person households, at a high risk for being food insecure; in fact, one in five households that rely on government benefits are severely food insecure.4

Cost of Other Basic Needs

Other factors that affect the ability to afford nutritious food include the cost of other basic needs, such as housing, where trade-offs may be made between purchasing food and paying rent or utility bills. Food insecurity is highest among those who rent, with 19% of tenants reported to be moderately or severely food insecure, compared to just 4% of homeowners.[xi]

Unexpected costs or events, such as major repairs or sudden job loss can affect the ability to afford food.

The cost of food itself can also pose a barrier, and recent increases in the price of food may affect lower-income households more severely.[xii]

Social Factors

Social factors such as the lack of transportation to access healthy food, the cultural appropriateness of available and affordable food lack of storage for healthy food, and a lack of time for the preparation of healthy food can also affect food security.

Impacts of Food Insecurity

Food insecurity can cause negative impacts to children’s long-term physical and mental health. It can increase their risk of conditions such as depression and asthma, increase the risk of suicidal ideation, and impact school performance and development.[xiii]

The impacts of food insecurity are experienced by adults as well; they are linked to overall poorer health and chronic conditions (such as depression, diabetes, and heart disease), and can lead to higher medical costs as existing medical conditions are difficult to manage.[xiv]

At its most extreme, food insecurity is also associated with premature mortality, with the average lifespan of adults from severely food insecure households being nine years shorter than those from food secure households.[xv]

Food insecurity also has important social impacts. The inability to provide adequate food can be associated with feelings of shame and a fear of blame. This may lead people to detach themselves from social life. Further, food is often an important form of socializing and the inability to offer food can lead to reduced socialization, particularly for children when parents cannot afford to offer food to childhood friends.[xvi]

Policy and Best Practice in Addressing Food Insecurity

Access to food is a basic human right. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights to which Canada is a signatory states: “The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions.” Article 11 (1). Looking at food insecurity with a human rights approach means that you understand that there are “certain rights that everyone is entitled to, regardless of who they are or where they come from”.[xvii] This approach views the lack of adequate food as a human rights violation, rather than simply the decisions made by individuals, or policies and programs not working.

One important approach to affecting the root causes of food insecurity is to address the link between income and food insecurity. This can be done by improving the financial resources of households with low incomes through specific policy interventions. Policies that increase wages and the quality of employment will reduce the risk of food insecurity among those who are employed. Enhancing Canada’s social protections through appropriate levels of income assistance would further ensure that those requiring income supports are not at risk of food insecurity. In particular, the introduction of a Universal Basic Income would address the problem of food insecurity broadly as food insecurity impacts a diversity of households, and a Basic Income Guarantee can universally reach any household with an inadequate income.[xviii]

Role of Psychology in Addressing Food Insecurity

Psychology has a critical role to play in food insecurity, along with poverty and homelessness, which are closely related.

In terms of mental health services, unfortunately, many people who are food insecure are unable to care for their basic needs. Economically, people who are food insecure are less likely to have sufficient income to pay for privately provided psychological services and are less likely to seek out psychological services. As such, psychologists can work with local housing services, shelter services, community organizations, and food banks – to name a few – to bring their services to these individuals on a sliding scale or pro bono manner. More psychologists should be included in more client-centered, recovery-oriented mental health service delivery at the community level.

Psychology also has a critical role to play in advocacy, particularly as relates to: 1) food availability (a reliable and consistent source of quality food); 2) food access (people have sufficient resources to produce and/or purchase food); 3) food utilization (people have sufficient food and cooking knowledge, and basic sanitary conditions to choose, prepare, and distribute healthy food to their families; and 4) stability (a stable and sustained environment to access and use healthy foods)[xix]. It also has a role to play in advocacy as relates to the, the social determinants of health, the need for affordable housing, the need for access to mental health services, and the interplay between mental health and the social determinants, which are often connected to food insecurity. Considering different system levels, at the micro-level, psychology can liaise with a client’s wider care team and community organizations to advocate for available, accessible, stable, and nutritious food sources. At the macro-level, psychologists can advocate at the community and larger levels for policy change, for the right to food security, universal basic income, funding of affordable and/or rent geared to income housing, increased social assistance, and access to mental health services.

Within academia, community psychology should be taught as part of introductory psychology courses, and more community psychology faculty and researchers should be hired.

In terms of research, psychology can be used to understand:

- Understand attitudes and behaviours of and towards those who experience food insecurity. This can include how to increase support and collective action towards food insecurity, along with identifying possible interventions – both individual and structural.

- Understand social responses to food insecurity that maintain barriers to addressing this problem.

- Evaluate effectiveness of public health initiatives and education to shift social responses to food security.

- Employ different research methodologies and approaches, including but not limited to collaborating with individuals with lived experiences and with Indigenous leaders.

- Exploring the different components of food insecurity, and how they in turn impact individuals of different walks of life.

Psychology can also facilitate forums in which different professions, organizations, and pioneer psychologist leaders in addressing food insecurity, can come together to have interdisciplinary conversations about solutions to food insecurity, and then present any findings via consolidated advocacy efforts to relevant government bodies and agencies.

For Additional Information

Additional information and resources about food insecurity in Canada are available from the following sources.

- PROOF (Food Insecurity Policy Research)

- Food Banks Canada

- Dieticians of Canada

- Community Food Centers Canada

- Food Secure Canada

You can consult with a registered psychologist to find out if psychological interventions might be of help to you. Provincial, territorial and some municipal associations of psychology often maintain referral services. For the names and coordinates of provincial and territorial associations of psychology, go to https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/PTassociations/.

This fact sheet has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by:

The Canadian Poverty Institute

Ambrose University

150 Ambrose Circle SW

Calgary, Alberta T3H 0L5

www.povertyinstitute.ca; povertyinstitute@ambrose.edu

Date: May 2023

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the Psychology Works Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

Canadian Psychological Association

Tel: 613-237-2144

Toll free (in Canada): 1-888-472-0657

hr

References

[i] FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2021. Transforming food systems for food security, improved nutrition and affordable healthy diets for all. Rome: FAO, 2021.

[ii] Tarasuk, V. & Mitchell, A., Household food insecurity in Canada, 2017-18. Toronto: PROOF, 2020.

[iii] PROOF Food Insecurity Policy Research, New food insecurity data for 2019 from Statistics Canada. Toronto: PROOF, 2022.

[iv] Caron, N. & Plunkett-Latimer, J. Canadian Income Survey: Food insecurity and unmet health care needs, 2018 and 2019. Statistics Canada: 2022.

[v] Food Banks Canada, HungerCount 2021. Mississauga: Food Banks Canada, 2021.

[vi] Hamilton, Taylor, D., Huisken, A., & Bottorff, J. L. (2020). Correlates of food insecurity among undergraduate students. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 50(2), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v50i2.188699

[vii] Meal Exchange. (2021). 2021 National Student Food Insecurity Report. Retrieved from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5fa8521696a5fd2ab92d32e6/t/6318b24f068ccf1571675884/1662562897883/2021+National+Student+Food+Insecurity+Report+-3.pdf

[viii] Tarasuk, V. & Mitchell, A., Household food insecurity in Canada, 2017-18. Toronto: PROOF, 2020.

[ix] Sauchyn, D., Davidson, D., & Johnston, M., Prairie Provinces; Chapter 4 in Canada in a Changing Climate: Regional Perspectives Report, Government of Canada: 2020.

[x] Tarasuk, V., Implications of a basic income guarantee for household food insecurity, Thunder Bay: Northern Policy Institute: 2017.

[xi] Statistics Canada. Household Food Insecurity in Canada. Ottawa: Government of Canada: 2020.

[xii] Agri-Food Analytics Lab, Canada’s food price report: 2022. Dalhousie University, University of Guelph, University of Saskatchewan, & The University of British Columbia: 2022.

[xiii] PROOF. Household food insecurity in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto. Available [online] https://proof.utoronto.ca/food-insecurity/. Accessed 18-03-2022.

[xiv] Tarasuk, V., Mitchell, A., & Dachner, N., Household food insecurity in Canada, 2014. Toronto: PROOF: 2016.

[xv] PROOF. Ibid.

[xvi] Purdam, K., E. Garratt and A. Esmail. “Hungry? Food Insecurity, Social Stigma and Embarrassment in the UK.” Sociology. Vol 50, No. 6: 1072-1088. December 2016.

[xvii] Canada Without Poverty, Human rights and poverty reduction strategies. Ottawa: Canada Without Poverty: 2015.

[xviii] Tarasuk, V., Implications of a Basic Income Guarantee for household food insecurity, Thunder Bay: Northern Policy Institute: 2017.