Concepts, Definitions and Measures

The common understanding of poverty is that it involves a critical lack of income that interferes with a person’s ability to meet their basic needs. The experience of poverty, however, is much more complex. The Oxford Multi-Dimensional Poverty Index (MPI) includes the following factors, in addition to income, as constitutive of poverty: quality of work; empowerment; physical safety; social connectedness; psychological well-being, and happiness.[i] The multi-dimensional nature of poverty is reflected in the definition of poverty that was recently adopted by the Government of Canada in its national poverty strategy. According to this definition, poverty is: The condition of a person who is deprived of the resources, means, choices and power necessary to acquire and maintain a basic level of living standards and to facilitate integration and participation in society[ii].

Despite the multi-dimensional nature of poverty, poverty measures continue to be based on income. One important measure of poverty is the Low Income Measure (LIM).

This internationally used measure defines a household as poor if it is earning less than 50% of the median income, adjusted for household size.

In Canada, the Market Basket Measure (MBM) has been adopted as the official measure of poverty. The MBM considers a household poor if its income is insufficient to purchase a basket of goods and services deemed essential for basic human functioning. Income thresholds are adjusted for household size and the region in which one lives.

In 2019, the income thresholds for a family of four (2 adults and 2 children) for major Canadian cities were as follows[iii]:

| Halifax – $46,147 | Winnipeg – $45,164 |

| Montreal – $41,090 | Calgary – $49,462 |

| Toronto – $49,304 | Vancouver – $50,055 |

Incidence of Poverty

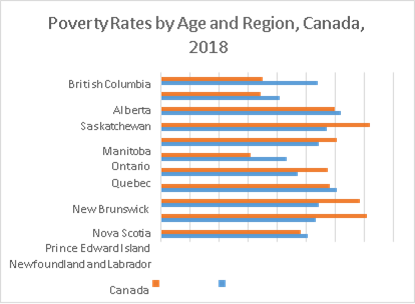

According to Canada’s official measure of poverty, 3.73 million Canadians were living in poverty in 2018, accounting for 10.1% of the population.

Poverty rates vary by region.

Just under 10% of children under the age of 18 were living in poverty that same year[iv].

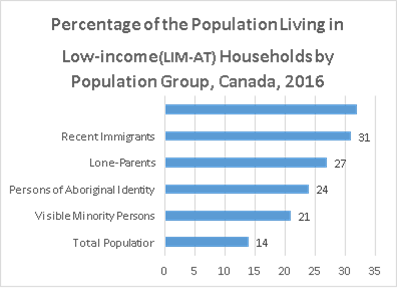

Profile

Certain population groups are at greater risk of poverty. In Canada, populations with a higher incidence of poverty include persons living alone, Indigenous persons, racialized persons, recent immigrants, persons with disabilities, and lone-parent families.[v]

Causes of Poverty

Poverty is often thought to result from the deficits of an individual. Lack of education or skills, poor language proficiency, mental health or addictions challenges, lack of financial literacy and poor life choices are some of the factors that can increase a person’s risk of poverty. While these factors do contribute to poverty, it is also important to understand the social conditions in which a person lives.

Where a person is in their life course is an important contributing factor. Stages of life where there is increased dependency, such as childhood or advanced age, increase the risk of poverty. Also at risk are caregivers who support people in dependent situations. Social connections also matter, as those who are isolated or living alone tend to have above average rates of poverty. The stigma attached to poverty can also limit one’s life choices.

Finally, systemic forces act to increase the risk of poverty. Workers employed in precarious positions that are part-time, insecure, and low-waged are at much greater risk of poverty. The lack of recognition of foreign credentials places many immigrants at an increased risk of poverty. Structural conditions including racism, discrimination, patriarchy, and the impacts of colonization are further factors that greatly increase the risk of poverty for people from particular social groups. The inadequacy of Social Assistance benefits further impacts those whose life circumstances require them to rely on income supports, leaving them in deep poverty.

Impacts of Poverty

Poverty comes at a cost. It is estimated that Canada spends between $72.5 and 86.1 billion annually due to the costs associated with poverty[vi] while the annual cost of homelessness is estimated at $7 billion.[vii]

Poverty is associated with reduced levels of trust and social cohesion that affect all of society.[viii]

Poverty also compromises the mental and physical health of adults and children and compromises cognitive functioning.[ix] The developmental impacts on children are particularly important as they can affect future life chances throughout adulthood, affecting biological, cognitive, emotional, and social domains of development. Lack of nutrition, increased experienced stress, decreased maternal supports, increased exposure to trauma and violent neighborhoods interact in a cumulative manner. Noted latent outcomes, resistant to intervention, result from permanent impacts on the developing brain. Specifically, the child is more likely to experience heightened anxiety, emotional difficulties, and difficulties in learning stemming from executive functioning deficits.[x] [xi] These outcomes limit gains in language development, reading and writing and social development. They may also result in problems maintaining healthy relations with parents, peers, and authority figures, such as teachers.[xii] [xiii] [xiv] These cumulative

impacts have been connected to increases in deviant behaviour, early pregnancy, and school dropout, thereby limiting social destinations that increase health and well-being.[xv] [xvi] [xvii]

Policy and Best Practice

Increasingly, poverty is understood as a violation of human rights. Under the international human rights framework of which Canada is a part, people are guaranteed the right to work, fair wages, safe and healthy working conditions, to form or join trade unions, an adequate standard of living, social security, food, clothing, housing, education, health care, and participation in cultural life.[xviii] From this standpoint, addressing poverty involves ensuring that the full array of rights people enjoy are realized. In 2018, Canada adopted a national poverty strategy called Opportunity for All.[xix] This federal strategy has three pillars:

- Dignity: Lifting Canadians out of poverty by ensuring basic needs—such as safe and affordable housing, healthy food, and health care are met

- Opportunity and Inclusion: Helping Canadians join the middle class by promoting full participation in society and equality of opportunity

- Resilience and Security: Supporting the middle class by protecting Canadians from falling into poverty and by supporting income security and resilience

The national strategy acknowledges that freedom from poverty is a human right.

Role of Psychology in Addressing Poverty

Psychology has a critical role to play in addressing poverty, along with homelessness and food insecurity which are often outcomes/consequences of poverty.

In terms of mental health services, unfortunately, many people who are experiencing poverty are unable to care for their basic needs and may subsequently experience in transient circumstances compounded by unmanaged mental health, trauma, or substance use challenges. Economically, people who are experiencing poverty do not have sufficient income to pay for privately provided psychological services, nor may they know where to begin in terms of finding a psychologist. As such, psychologists can work with local housing, shelter, or community services to bring their services to where the impoverished are, and if able, to do so on a sliding scale or pro bono manner. More psychologists should be included in more client-centered, recovery-oriented mental health service delivery at the community level.

Psychology also has a critical role to play in advocacy, particularly as relates to the anti-poverty initiatives, social determinants of health, the need for affordable housing and food security, the need for access to mental health services that are covered under provincial health plans, and the interplay between mental health and the social determinants. Considering different system levels, at the micro-level, psychology can liaise with a client’s wider care team and community organizations to ensure their core health and psychological needs are met. At the macro-level, psychologists can advocate at the community and larger levels for policy change, for funding of affordable and/or rent geared to income housing, food security, increased social assistance, access to mental health services, and coverage of psychological services under provincial health plans.

Within academia, community psychology should be taught as part of introductory psychology courses, and more community psychology faculty and researchers should be hired.

In terms of research, psychology can be used to understand:

- Understand attitudes and behaviours of and towards those who experience poverty. This can include how to increase support and collective action towards combatting poverty, along with identifying possible interventions – both individual and structural.

- Understand social responses to poverty that maintain barriers to addressing this problem.

- Evaluate effectiveness of public health initiatives and education to shift social responses to poverty.

- Employ different research methodologies and approaches, including but not limited to collaborating with those with lived experience and with Indigenous leaders.

- Exploring how poverty impacts individuals of different walks of life.

Psychology can also facilitate forums in which different professions, organizations, and pioneer psychologist leaders in addressing poverty, can come together to have interdisciplinary conversations about solutions to poverty, and then present any findings via consolidated advocacy efforts to relevant government bodies and agencies.

For Additional Information

- National Advisory Council on Poverty https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/poverty-reduction/national-advisory-council.html

- Canadian Poverty Hub povertyhub.ca

- Canada Without Poverty cwp-csp.ca

- Tamarack Institute for Community Engagement tamarackcommunity.ca

You can consult with a registered psychologist to find out if psychological interventions might be of help to you. Provincial, territorial and some municipal associations of psychology often maintain referral services. For the names and coordinates of provincial and territorial associations of psychology, go to https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/PTassociations/.

This fact sheet has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by:

The Canadian Poverty Institute

Ambrose University

150 Ambrose Circle SW

Calgary, Alberta T3H 0L5

www.povertyinstitute.ca; povertyinstitute@ambrose.edu

Date: May 2023

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the Psychology Works Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

Canadian Psychological Association

Tel: 613-237-2144

Toll free (in Canada): 1-888-472-0657

References

[i] Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative. https://ophi.org.uk/research/multidimensional- poverty/ Accessed 19 January 2022.

[ii] Government of Canada. 2018. Opportunity for All: Canada’s First Poverty Reduction Strategy Ottawa: Government of Canada.

[iii] Statistics Canada. Table 11-10-0066-01 Market Basket Measure (MBM) thresholds for the reference family by Market Basket Measure region, component, and base year. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1110006601

[iv] Statistics Canada. Table 11-10-0135-01 Low-income statistics by age, sex, and economic family type. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1110013501

[v] Statistics Canada. 2016. Census of Canada.

[vi] Government of Canada. 2010. Federal Poverty Reduction Plan: Working In Partnership Towards Reducing Poverty In Canada. Report of the Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities. Ottawa: Government of Canada.

[vii] Gaetz, S., J. Donaldson, T. Richter and T. Gulliver-Garcia. 2013. The State of Homelessness in Canada 2013. Toronto: The Canadian Observatory on Homelessness and the Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness.

[viii] Ross, C. 2011. “Collective Threat, Trust and the Sense of Personal Control.” Journal of Health and Social Behaviour 52, no. 3 (September).

[ix] Mikkonen, J., & Raphael, D. 2010. Social Determinants of Health: The Canadian Facts. Toronto: York University School of Health Policy and Management.

[x] Anasuri, S. 2017. Children living in poverty: Exploring and understanding its developmental impact. Journal Humanities and Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) 22, (6), Ver. 9 (June. 2017) PP 07-16.

[xi] Barch, D., Pagliaccio, D., Belden, A., Harms, M. P., Gaffrey, M., Sylvester, C. M., Tillman, R., & Luby, J. (2016). Effect of Hippocampal and Amygdala Connectivity on the Relationship Between Preschool Poverty and School-Age Depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(6), 625–634.

[xii] Anasuri. 2017. Ibid.

[xiii] Chaudry, A., & Wimer, C. 2016. Poverty is Not Just an Indicator: The Relationship Between Income, Poverty, and Child Well-Being. Academic Pediatrics, 16 (3 Suppl), S23–S29.

[xiv] Hyde, L. W., Gard, A. M., Tomlinson, R. C., Burt, S. A., Mitchell, C., & Monk, C. S. 2020. An ecological approach to understanding the developing brain: Examples linking poverty, parenting, neighborhoods, and the brain. American Psychologist, 75(9), 1245–1259.

[xv] Anasuri. 2017. Ibid.

[xvi] Larson C. P. (2007). Poverty during pregnancy: Its effects on child health outcomes. Paediatrics & Child Health, 12(8), 673–677.

[xvii] Maggi, S., Irwin, L. J., Siddiqi, A., & Hertzman, C. (2010). The social determinants of early child development: an overview. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 46(11), 627–635.

[xviii] Canada Without Poverty. n.d. Human Rights and Poverty Reduction Strategies: A Guide to International Human Rights Law and its Domestic Application in Poverty Reduction Strategies. Ottawa: Canada Without Poverty.

[xix] Government of Canada. 2018. Ibid.