As this year’s Black History Month closes, CPA President Dr. Eleanor Gittens shares her reflections on Black History Month.

Produced by Kate Eggins

CPA President, Dr. Eleanor Gittens, discusses how to be an ally to individuals and groups experiencing marginalizations.

Produced by Kate Eggins

An Alberta psychologist’s tribute to Nelson Mandela

Alberta psychologist Zuraida Dada grew up in Apartheid South Africa, and was a part of the fight against oppression that finally succeeded with the formation of a democratic government in 1994. In this article, she pays tribute to the leader and face of the anti-Apartheid movement, the late icon Nelson Mandela. This article was first published in the College of Alberta Psychologists CAP Monitor Spring 2023 edition, and was re-published in the CPA’s counselling section’s Kaleidoscope newsletter in December 2023.

An Alberta psychologist’s tribute to Nelson Mandela

by Zuraida Dada, R. Psych., C.Psych., CPHR (Ret.)

Apartheid

The term Apartheid is an Afrikaner word which means “separateness.” Apartheid was in place in South Africa from 1948 to 1994. Apartheid was malevolent in its intent, with its goal being the annihilation of the BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Colour) communities. Apartheid was legalised oppression and was socio-economic and political in nature. The Apartheid government used every legal means in pursuit of this goal, including but not limited to:

- Population registration and segregation

- Job reservation and economic apartheid

- Segregation in education

- Land tenure and geographic segregation

- Sexual apartheid

- Pass laws and influx control

- Political representation

- Separate development and Bantustans

- Banning, detention without trial and state security

Apartheid was pervasive and governed every aspect of our lives, from cradle to grave. For BIPOC people living under apartheid, it meant living without freedom and in perpetual fear. Nelson Mandela successfully led the country to freedom peacefully (without a war/formal bloodshed) and was the first Black President of post apartheid, democratic South Africa.

How do I begin to pay tribute to a father figure and someone who has left an indelible mark on me and every aspect of my life? There can never be sufficient words to convey the depth of the impact that Nelson Mandela (or Tata Madiba as he is fondly known), had on me. I will try my best to share a few ideas that Tata Madiba taught me through his words and actions, and that I strive to apply in my personal and professional life.

Lessons from Nelson Mandela (Tata Madiba)

Tata Madiba taught me:

- About “Amandla” meaning power—more specifically, the power of freedom—that freedom is like oxygen; you realize only in its absence how precious it is. Under apartheid, we did not have access to psychologists. This idea underpinned the reason I became a psychologist. It has imbued my life. It is the premise of my advocacy work. It is what I strive for: freedom from oppression, racism, violence, bias, prejudice and discrimination. The idea that striving for freedom from racism and discrimination is as vital as breathing has enabled me to understand my client’s reactions to racism, allowed me to be more empathetic and taught me that freedom from racism is necessary and vital for the survival and thriving of BIPOC people.

- That power comes in many forms, and that with power comes significant responsibility to act with discipline and to accept the consequences of one’s actions. As psychologists, it is critical that we understand the power dynamics in our relationships with our clients. Our clients generally seek therapy when they are at their most vulnerable, and often share aspects of their lives they have never shared before. As psychologists, we need to hold that space sacred and be aware/mindful of the power we have and the role we play vis-a-vis our clients. It is the bedrock of clinical practice to be mindful of the power dynamic and to do all we can to recalibrate it and not abuse that power.

- About the nature of oppression and racism—that racism is a pervasive ideology premised on power, privilege and fear. It is a form of violence. It thrives in silence. It is traumatic to experience. Racism denialism is trauma inducing and to recognise, acknowledge and accept that racism exists is the first step toward healing. This has informed the approach I use when working with clients who have experienced racism/discrimination. I use a compassion-focused, trauma-informed approach and provide psychoeducation regarding racism, power and privilege, along with strategies for managing this. Unfortunately, I have had first-hand professional encounters of racism denialism by fellow psychologists, which, as a BIPOC individual, is trauma-inducing. As psychologists, it is our ethical obligation and professional duty to be objective and to provide professional services free of bias. Given the trauma that racism denial causes, it is my fervent belief that racism denial should be treated in a manner analogous to sexual harassment, and should be grounds for ethical misconduct as well as professional incompetence.

- About the importance of values and the role they play in our lives. Tata Madiba famously said at his Rivonia trial on 20 April 1964: “I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.” I believe that racism (and the fight against oppression) is premised on personal values which then are enshrined in our daily lives, resulting in systemic and internalised racism. It is incumbent on us as psychologists to constantly engage in self-reflection; to be aware of the dynamics of the society in which we live; to understand the nature of racism so we can support, in healthy and meaningful ways, our clients who experience it; to accept and be aware of our limitations; to engage in appropriate activities, such as referring clients to others more competent than ourselves when the situation warrants; to obtain training when necessary; and to engage in client and social justice advocacy.

- About the power of one—how one person's actions can impact millions. As a psychologist I am constantly reminded of the impactful and meaningful work we do. The work we do matters, and is often the turning point in people’s lives that has a ripple effect on communities and societies at large. The key building block of every healthy society is a healthy person. As psychologists, our role is to build healthy communities and societies, one person at a time.

- To choose the pen over the sword. As a psychologist, I am constantly reminded of the power my words have on my clients as well as the power of each person’s own words on their sense of self, their identity and their own life.

- Deeds count over words. As psychologists it is incumbent on us to “be the change we want to see in this world” and to engage in social advocacy and social justice initiatives, not just limiting our advocacy to words alone.

- About the generosity of the human spirit/love over evil/hatred. Tata Madiba famously said, “No one is born hating another person because of the colour of his skin, or his background or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.” This is the basis of the work I do as a psychologist. As psychologists in the context of client advocacy and social justice, it is incumbent upon us to acknowledge this truth and to base our work on this truth if we are to build an equal and just society.

- About the importance of truth and owning your own truth. As psychologists it is critical that we speak and own our own truth, as well as create a safe, judgment-free space in which clients can express and own their own truths.

- The importance of forgiveness over resentment. Forgiveness is a key principle in my work as a psychologist when supporting clients who have experienced racism and discrimination; this is especially so in my social justice work. I believe forgiveness is the antidote to resentment; it is self care; it is self compassion; it is the building block of resiliency and is a necessary first step in healing from trauma.

- The importance of understanding over ignorance. “Seek to understand, rather than to be understood.” This allows for empathy and for the building of a healthy therapeutic alliance. Understanding that racism denialism is a form of ignorance and is trauma inducing is vital to any work we do with clients who experience racism/discrimination.

- The importance of humility over arrogance. Recognising our limitations as psychologists is a form of humility. Racism denial is a form of arrogance. It is critical for us to understand the importance of engaging with clients in humility and renouncing arrogance, to create healthy therapeutic alliances in effective support of our clients.

- The importance of flexibility over rigidity. As a psychologist, the importance of being able to adopt a flexible approach is a key aspect in the provision of effective therapy.

- The importance of action over apathy. As psychologists we need to recognise the important active role we play in the creation of healthy societies—especially in relation to client advocacy and advocacy in society in general. Apathy can be equated to incompetence and unethical conduct.

- The importance of resilience over surrender. Resilience is the key building block of healthy and thriving individuals and healthy societies. It is the cornerstone of the work I do with my clients.

- The importance of courage over cowardice. As psychologists, it is incumbent upon us to have the courage to change things over which we have control, to advocate for our clients, to fight against injustice, to lobby for changes and to do research that allows the science to move forward.

- The importance of fairness over injustice. As psychologists have a vital role in social justice. All social justice is built on the premise of fairness and the creation of fairness in society.

- The importance of kindness over cruelty. Unconditional positive regard is the basis of our work as psychologists. Recognising that racism and racism denial are trauma is a form of kindness. Racism denial is cruelty and traumatic.

- About “Ubuntu”—which means humanness or human kindness, the ties that bind the human spirit. Ubuntu asserts that society, not a transcendent being, gives human beings their humanity. It is the recognition that we are all bound in ways that are invisible to the human eye. Michael Eze said, "We are because you are, and since you are, definitely I am. Humanity is a quality we owe each other. We create each other and need to sustain this otherness creation.” Barack Obama said, “There is a oneness to humanity that we achieve ourselves by sharing ourselves with others and by caring for those around us.." Ubuntu imbues the work I do, recognising we all need one another and that the sum is greater than the parts. We all have a role to play in eradicating injustice, be it as advocate or ally.

- To challenge myself to find this truth within myself—to identify my values, my beliefs and my identity within the context of the greater brotherhood and sisterhood of humanity. To:

- always remember the generosity of the human spirit;

- engage with people at a human level—as human beings first;

- understand my brother and my sister first, before judging them;

- approach life with empathy;

- find opportunities to nurture and care for others; and,

- take accountability for my life and my actions.

Tata Madiba often quoted the poem Invictus: "It matters not how straight the gate, how charged the punishment, the scroll, I am the master of my fate, the captain of my soul."

As Barack Obama said: “Tata Madiba makes me want to be a better human being and speaks to what is best inside all of us. The challenge for all of us is to search for that within ourselves and to make his life's work our own.” Challenge accepted, Tata Madiba, challenge accepted.

Hamba kahle Tata Madiba, Hamba kahle (Go well Tata Madiba, go well).

Ndiyakukhumbula (I will miss you).

Enkosi, Ngiyabonga, (Thank you).

V-TRaC Lab

The Vulnerability, Trauma, Resilience and Culture Research Laboratory (V-TRaC) is based at the University of Ottawa. It studies the connection between vulnerability and trauma and the coping strategies that might be employed to deal with either – or both. Their research is wide-ranging and covers many topics, from child welfare in Ontario to psychosocial interventions related to Ebola Virus Disease in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The Vulnerability, Trauma, Resilience and Culture Research Laboratory (V-TRaC) is based at the University of Ottawa. It studies the connection between vulnerability and trauma and the coping strategies that might be employed to deal with either - or both. Their research is wide-ranging and covers many topics, from child welfare in Ontario to psychosocial interventions related to Ebola Virus Disease in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The V-TRaC lab has authored recommendations to reduce racial disparities in Ontario Child Protective Services, has created the course ‘How To Provide Antiracist Mental Health Care’ (approved for continuing education credits by the CPA) and is currently evaluating mental health problems among immigrant populations.

Their work over the past several years has produced many publications and fact sheets, but their greatest impact might be in advancing the conversation when it comes to the social determinants of mental health. In 2022, the V-TRaC lab organized a conference, the first of its kind geared toward addressing barriers to Black mental health care in Canada. V-TRaC’s founder, Dr. Jude Mary Cénat, has also created the Interdisciplinary Centre for Black Mental Health, the first Canadian research centre entirely dedicated to the study of the biological, social and cultural determinants of health of Black people in Canada.

The resources created by the V-TRaC lab are helping many people right now, and the research they are conducting is filling a void in psychological and mental health research that will help many more people in the years to come.

Read more about the V-TRaC lab’s director, Jude Mary Cénat, in this 2022 Black History Month profile.

Canada Confesses

Canada Confesses started in 2020 as a youth-led platform for Canadians to anonymously share their experiences with racial and social injustice. Since that time, it has expanded a great deal, with more than 40 volunteers working together across Canada, and has become a resource to connect people across the country interested in making changes to the structures and systems that have led to inequality and marginalization.

Canada Confesses started in 2020 as a youth-led platform for Canadians to anonymously share their experiences with racial and social injustice. Since that time, it has expanded a great deal, with more than 40 volunteers working together across Canada. It has become a resource to connect people across the country interested in making changes to the structures and systems that have led to inequality and marginalization. It has built an enormous library of free essential support resources for Canadians. And they have engaged with policy-makers, community leaders, and mental health professionals at dozens of organizations to further their message and advocacy.

The Canada Confesses resource database is remarkable, having collected thousands of resources on a myriad of topics, including – Immigrants and Refugees, Black communities, anti-bullying and anti-racism, sexual and domestic violence – the list goes on. Their activism glossary is almost as extensive, and a significant resource for people who want to understand terms like “white-centering”, “microaggressions”, and “intersectionality”. And their original platform of “confessions” continues to grow as more and more Canadians share their experiences of discrimination – like misogynoir, ableism, and racial profiling.

While these testimonials are labeled as ‘confessions’, it is not really the person writing who is ‘confessing’ – it is Canada. Hence the name Canada Confesses. Many of us like to think of our country as one where racism exists in the margins, and where discrimination has largely been eradicated in our hiring practices, societal structures, and daily lives. It’s important to have a reminder, every now and then, that racism and discriminatory practices remain prevalent in Canada. If we are aware of this, and we want to do something about it, Canada Confesses is a good place to start.

Listen to the Mind Full podcast episode with the Canada Confesses co-founders “Canada Confesses creators Nancy Tangon and Priscilla Ojomu”

Black Mental Health Canada

This week’s Black History Month spotlight is on Black Mental Health Canada. They are an organization that educates Canada’s Black community about mental health, and advocates for culturally-affirming care through training and workshops.

The primary goal of Black Mental Health Canada (BMHC) is to educate Canada’s Black community about mental health - that it’s a real issue, that people struggle with mental health problems, and that supports are available. There have been years of stigma that have prevented many Black Canadians from engaging with mental health professionals. BMHC maintains a list of mental health providers that work with the Black community. Practitioners can register their practice and people seeking help can find a culturally competent professional to provide that help.

BMHC is also committed to being an advocate for culturally-affirming care. Because of the history within Canada, and North America as a whole, the needs of Black people are unique. Past abuses and the way the Black community has been approached by the mental health establishment have eroded the trust between the community and the system. To educate the Black community on mental health, there also have to be specific supports tailored to the specific needs of that community. BMHC provides EDI training and consulting as well as public and custom-built workshops for both mental health professionals and the public.

BMHC is dedicated to education and training, which is currently geared toward clinicians, so they are able to provide racially equitable and culturally affirming care. They also engage in advocacy, where BMHC representatives engage with governments and leaders about dismantling the stigma surrounding Black mental health. This advocacy extends to overall mental health, specifically what that looks like and what that means for the Black community in Canada.

Listen to the Mind Full podcast episode with BMHC Research Lead Shanique Victoria ‘Making connections: Shanique Victoria and Black Mental Health Canada’

Dr. Herman George Canady

Herman George Canady has had a lasting influence on psychology, influencing theories like intergroup anxiety and stereotype threat. He was also one of the very early leaders in organizing a group of Black psychologists.

The current psychological theory of ‘intergroup anxiety’ describes a feeling of discomfort many people feel when interacting with people from groups that are not their own. A lot of that theory owes a great deal to Herman George Canady, whose work looked at Black students interacting with white examiners while taking IQ tests. If the examiner is white, and the Black child has experienced discrimination and prejudice from white people in the past, they are likely to be anxious and perform poorly on the test simply because it is administered by a person whose presence makes them nervous.

Dr. Canady’s study ‘The Effect of ‘Rapport’ on the I.Q.: A New Approach to the Problem of Racial Psychology’ was the first of its kind to look at intelligence tests through this lens and led to many further studies examining the effect of a distrust of White people on the test scores of Black children. In many ways, Canady was one of the first psychologists to focus research on the Black experience in the United States.

This lack of Black inclusion in research, and a lack of psychological knowledge for Black Americans in general, led Dr. Canady to lead a movement organizing Black psychologists. He wrote A Prospectus of an Organization of Negroes Interested in Psychology and Related Fields and sent it to fellow members of the American Teachers Association (formerly the National Association of Teachers in Colored Schools), proposing a psychology section within the ATA.

Canady presented his proposal at the ATA convention, held at the Tuskegee Institute, in 1938. It was unanimously approved – but then quickly derailed by the onset of World War II. In later years the cause would be taken up again when Black psychologists organized at an APA convention in 1968 to discuss their dissatisfaction with "psychology's exploitations and the white definitions for behavior that placed Blacks in a negative light."

Dr. Canady obtained his B.A., his Master’s, and his Ph.D. from Northwestern University. He later served 40 years as the chair of the psychology department at the West Virginia Collegiate Institute (now West Virginia State College) before his retirement in 1968. He died in 1970, but his influence is still felt in intergroup anxiety research, stereotype threat studies, and in the ongoing effort to move psychology out of a white-centric model.

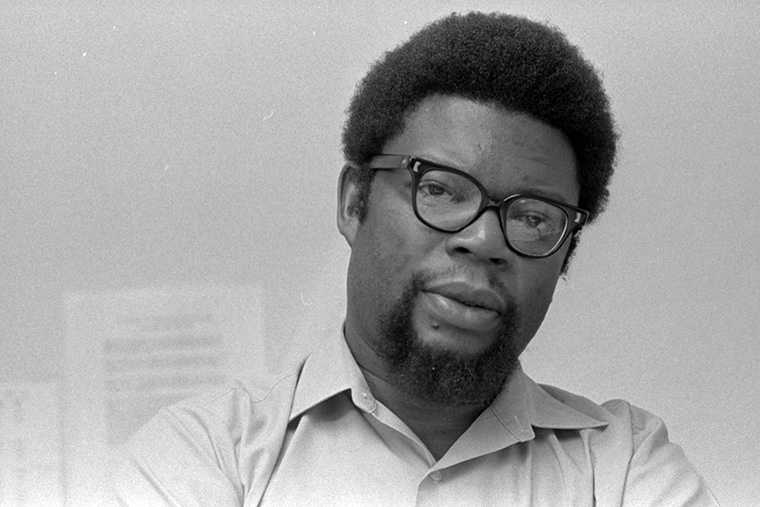

Dr. Robert Lee Williams II

Famous for three important books, and for coining the word ‘Ebonics’, Dr. Robert Lee Williams II spent his long and influential career combatting the racist stereotype that Black people were less intelligent than White people.

“Cars is whips and sneakers is kicks

Money is chips, movies is flicks”

- Big L., ‘Ebonics’

The word ‘Ebonics’ didn’t exist before 1973, when Dr. Robert Lee Williams II took the word ‘ebony’ and the word ‘phonics’, combined the two, and coined a brand new term for “linguistic and paralinguistic features which on a concentric continuum represent the communicative competence of the West African, Caribbean, and United States slave descendants of African origin." His 1975 book Ebonics: The True Language of Black Folks, traced the roots of Ebonics to Africa, arguing against the prevailing prejudiced opinion that Ebonics was just slang, or bad English.

Dr. Williams was born in Arkansas in 1930, and enrolled in Dunbar Junior College at the age of 16. He dropped out after only one year, having become quickly disillusioned upon being asked to take an IQ test. The results of the test suggested he was more suited to manual labour than he was to more intellectual pursuits. While this test had a huge impact on his self-esteem, racial bias in standardized testing later became the driving force behind some of his most important work. In particular, the Black Intelligence Test of Cultural Homogeneity, or BITCH-100, which he created in 1972 to account for the cultural factors affecting Black Americans differently than White Americans.

Dr. Williams obtained his Ph.D in clinical psychology in 1961 from Washington University, and in 1968 was a co-founder of the Association of Black Psychologists, later serving as its second President. The ABP was created as an alternative to the American Psychological Association, which was criticized for intentional and unintentional support of a structurally racist American society. The ABP’s membership saw themselves as “Black people first, psychologists second”.

He went on to found the first department of Black Studies at Washington University, where he worked as a professor of psychology, African studies, and African-American studies from 1970-1992. He continued to maintain a high profile through media appearances supporting his books – 1981’s The Collective Mind: Toward an Afrocentric Theory of Black Personality, 2007’s “Racism Learned at an Early Age through Racial Scripting”, and 2008’s History of the Association of Black Psychologists: Profiles of Outstanding Black Psychologists.

Dr. Williams was married to his wife, Ava Kemp, for 70 years until she died in 2018. He passed away in 2020 at the age of 90. He had eight children, four of whom went on to become psychologists.

Dr. Ruth Winifred Howard

One of the first Black women to earn a Ph.D. in psychology, Ruth Winifred Howard trained Black nurses and worked with children and youth during her long and exemplary career.

There is some debate as to who was the first Black woman to obtain a Ph.D. in psychology. Some say it was Inez Beverly Prosser, who received her Ph.D. in 1933 from the University of Cincinnati. Others think it was Ruth Winifred Howard, since they consider a psychology Ph.D. to count only if it comes from a psychology program – she graduated in 1934 with a doctorate in psychology and child development from the University of Minnesota. There is no record of whether either woman cared at all about the distinction.

Ruth Winifred Howard was born in 1900 in Washington D.C. Her father was the minister at the Zion Baptist Church and was heavily involved in many community initiatives. Ruth would later say this example was what led her to desire a career helping others, and led her on the path to becoming a psychologist. That path began at Simmons College in Boston, where she majored in social work and earned a Bachelor’s Degree in 1921. It ended at the University of Minnesota, where she obtained her psychology Ph.D. 13 years later.

For her doctoral research, Dr. Howard studied triplets. Specifically, she launched the most comprehensive study ever done on triplets, studying more than 200 sets ranging in age from birth to their 70s. For reasons yet unknown, it took more than a decade for that research to be published, in 1946 in the Journal of Psychology and in 1947 in the Journal of Genetic Psychology. By then, she had married fellow psychologist Albert Sidney Beckham and moved to Chicago.

With her husband, Dr. Howard opened a private practice where she worked with children and youth, while working as a psychologist at the dated and terribly-named McKinley Center for Retarded Children. She was also the staff psychologist at the Provident Hospital School of Nursing, training Black nurses, and was a psychologist for the Chicago Board of Health until 1972.

In 1964, Ruth’s husband Albert died. She kept working for a few more years, both in private practice and with the Chicago Board of Health. Dr. Ruth Winifred Howard died in 1997, just a few days shy of her 97th birthday, having left an important legacy. More than just a pioneer, paving the way for others to follow in her footsteps, Dr. Howard’s work made a marked difference in the lives of hundreds of children in Chicago and around the world.

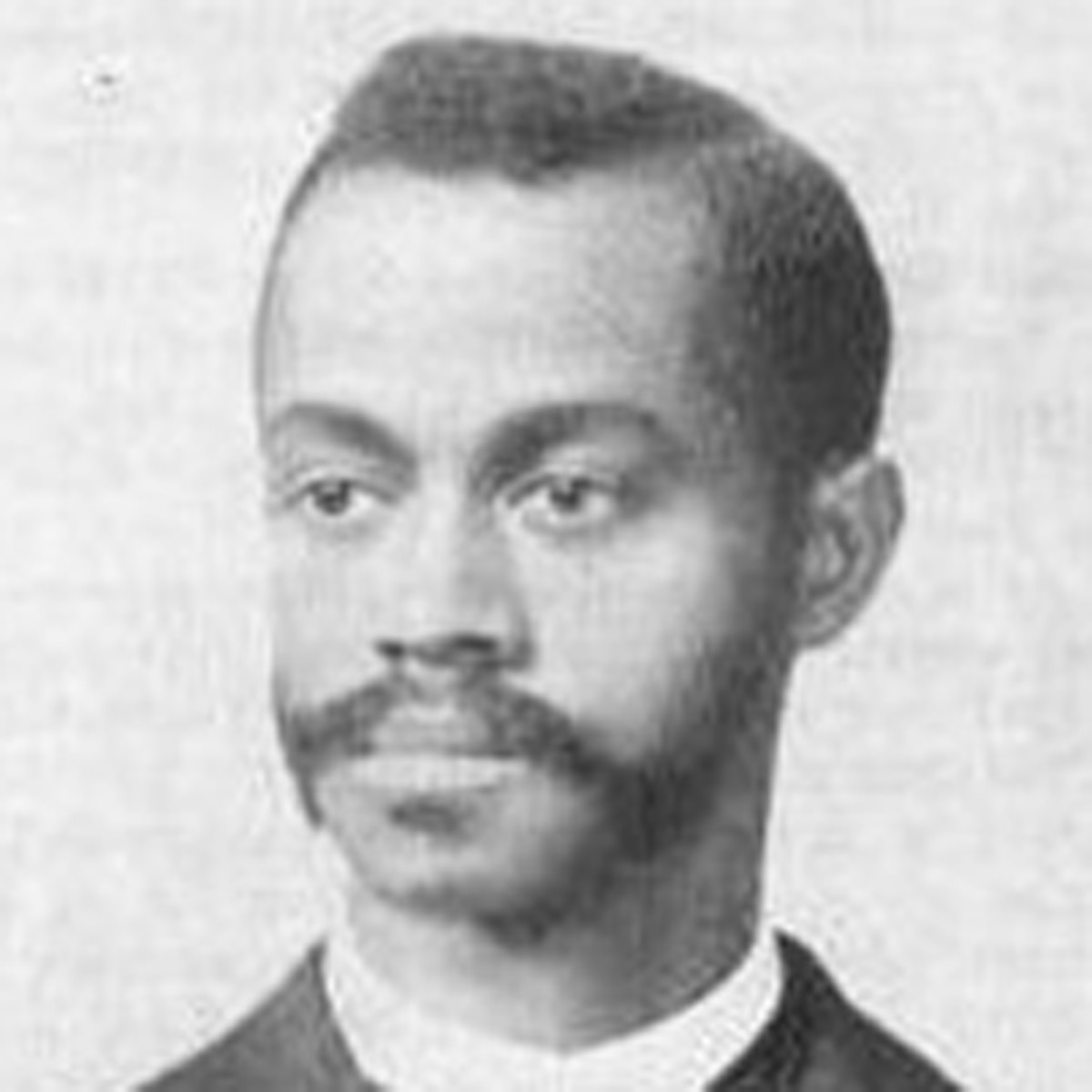

Dr. Francis Cecil Sumner

The first Black person to earn a Ph.D. in psychology, Francis Cecil Sumner spent his career working to elevate African-American education through more funding and more teaching of Black history.

The first Black person to receive a Ph.D in psychology, Francis Sumner was born in Arkansas in 1895. His parents worried about the quality of the education young Francis was receiving at his local elementary school, and so they taught him at home from what books they had available. When he applied to Lincoln College, a historically black university now known as Lincoln University, his application cited ‘private instruction in secondary subjects by father’ as he did not have a high school diploma.

Dr. Sumner passed the entrance exam and began his schooling at Lincoln at the age of 15. At 19, he graduated as valedictorian with a degree in philosophy. He moved on to Clark University for a second bachelor’s degree, where he became part of a mentor-mentee relationship with then-President of Clark, the pioneering psychologist G. Stanley Hall.

Sumner was drafted into the US military in 1918 and served in Germany in World War I before returning to Clark to complete his doctorate in 1920. Then, as now, psychological science was very Eurocentric, and Dr. Sumner focused on dismantling the racism and bias influenced by that Eurocentrism. Specifically, the studies at the time that purported to show intellectual inferiority in African-Americans. He tackled inequality in the judicial system and unequal outcomes in mental health between people of different races.

In 1939, his application for membership in the Southern Society for Philosophy and Psychology was rejected, after the SSPP changed its bylaws for the express purpose of excluding a Black member. Other members of the society threatened to resign if Dr. Sumner was not accepted, and his application was eventually improved, with the leadership of the society blaming a secretary.

From 1928 until his death, Dr. Sumner served as the chair of the psychology department at Howard University, a historically Black research university in Washington D.C. While there, he taught many Black psychology students including Kenneth Bancroft Clark, an influential leader in the civil rights movement and the first Black president of the American Psychological Association.

Dr. Sumner’s legacy endures to this day, as his lifelong efforts to elevate African-American education through more funding and more teaching of Black history and the Black experience have influenced modern education in many ways. Upon his death, he was memorialized with tributes of all kinds, including some that referred to him as ‘Howard’s most stimulating scholar’ and others that called him the ‘Father of Black Psychology’.

Photo: Enje Daniels Photography

Dr. Cranla Warren

Dr. Cranla Warren is the Vice-President of Leadership Development at the Institute for Health and Human Potential. Her professional work focuses on organizational systems, leadership development, and emotional intelligence, and her volunteer work focuses on mentorship for professional women and Black girls.

“You’ve been my therapist since we were 13 years old.”

Dr. Cranla Warren’s lifelong friend reached out to congratulate her on being named one of the Top 100 Accomplished Black Canadian Women for 2022. She said she wasn’t surprised that Dr. Warren was being so honoured, since she had been helping people as long as she could remember. Which included being a de-facto “therapist” for her friends from a very young age. "I never doubted you would be a therapist, as you were mine since I was 13! But now you have helped so many people over the years, whose lives were no doubt changed for having known you."

For Dr. Warren, that passion went beyond simply being a shoulder to cry on, or a sympathetic listening ear. She was the person to whom all her friends came to talk about their struggles or their issues, and she started to actively study what drove and motivated people. She started to read psychology books – there weren’t a lot of them in the 70s, but she read every one she could find. Like books by Dr. Joyce Brothers, one of the very few well-known female psychologists at the time.

“I became a student of human behaviour in my teens, reading everything I could, trying to understand everything that I could. I realized this was the path I wanted to take, but it was a very circuitous route.”

That route started out in social work, moved into psychotherapy, then into business. Through it all, Dr. Warren remained a student of human behaviour, figuring out how to connect with people at every step along the way. She obtained a Ph.D. in Organizational Psychology. She is currently the Vice-President of Leadership Development at the Institute for Health and Human Potential (IHHP), where Dr. Warren specializes in organizational culture and (as the title implies) leadership development.

Much of her success as a psychologist, a professional, and a person has come about as a result of her ability to understand others. But that success was not easy to attain, and got off to something of a rocky start.

“Don’t worry about becoming a psychologist, that it isn’t in the cards for you because you have too many strikes against you. Go for something that’s attainable, like becoming a secretary.”

This was the advice given to a young Cranla Warren by a guidance counselor before she applied to university, before she began to shape her career path, and before she had the “Dr.” in front of her name. The ‘strikes’ were that she was a Black girl – someone for whom academic success was unlikely, and for whom the path to that success was filled with dozens of barriers that did not exist for others. She overcame those barriers thanks, she says, to a very supportive family and series of great mentors. Not only through school, but through her professional life afterward.

“I’m very fortunate, I realize that every day. I’ve had incredible mentors through every step of my professional journey. I think, though, that I was vocal in seeking them out. Not everybody knows how to be proactive in doing this. When I was hired on at a pharmaceutical company I had worked in a hospital, I’d been a clinician, but I’d never worked in a business. I had done a talk, someone had seen it, and they loved what I presented, and they knew I was an advocate for mental health. They wanted someone like me to be in their medical education group. I got connected to the people who were in the seats of power, who said ‘I believe in what I see you doing and I’m going to help you rise in this organization’. Even though it may have been a potential career hazard for them. My advocates, mentors, and sponsors in the business world have always been white men, because that’s where the seat of power has traditionally been held.”

That proactive approach to seeking mentors and sponsors within an organization is one Dr. Warren imparts to many professional women, who seek her out for that very purpose. She mentors so that women and girls can see and work with someone who represents them, knows them, sees them and is also in a position of influence and power to a certain degree. The hope is that in these circumstances, and one day in all circumstances, these women and girls will no longer have to rely on white men to be their sole mentors as more and more women and people of colour assume leadership roles.

“I get sought out quite often by women, women of colour in particular, who say they want to learn how to crack the glass ceiling as it exists in their organization. They want to be leaders in their companies. But they keep bumping up against so many systemic barriers that they don’t quite know how to navigate. I’m trained as a coach, and I help coach them to create a development plan that’s separate from their organization to get them on a leadership path. A lot of it starts with self-awareness, emotional intelligence, how are you showing up? From there it broadens to the organization itself. Who can mentor them? Who might be a potential sponsor? Black women are often overlooked, and are invisible in many organizations.”

Dr. Warren has deconstructed her own path in order to see where the barriers lie, where the seats of power are concentrated, and what is required to break through in organizations for Black women in particular.

“Unless you have someone who has a seat at the table who’s advocating for you, who’s your champion and sponsor, who’s talking about you and your capabilities when you’re not in that room, it’s very, very hard to move forward.”

Having deconstructed her own path, and helped to create a path for many Black women to succeed in organizations across North America, Dr. Warren doesn’t stop there. The idea of mentorship, and the value that it imparts, is core to her philosophy in every way. She extends that idea to women and girls in her area as well.

“I’ve been a mentor for Black women and girls for probably 20 years. In the last decade, very formally, under the umbrella of a group called Trust 15, where I worked with their founder Marcia Brown to help provide very different experiences for the people in their programs Girls on the Rise and Ladies on the Rise. They hadn’t met anybody who had my level of education before, and I was driving into Toronto to be a role model, to be a mentor, to support them to effectively create their dreams and then to make a plan to achieve them.”

Dr. Warren created a program that brings young inner city Black youth she mentors to Stratford, where she lives, to take in the famous Stratford Festival. The young people get to tour the warehouse area and meet all kinds of people involved with the theatrical productions from actors to set designers. They come out of the experience with a newfound sense of what is possible. You can get work designing costumes, creating props, or making wigs? You mean those could be actual jobs?

“That advice I got [not to aim too high] from my guidance counselor was in the 70s, and here we are in the 2020s and young black girls are still receiving that same message. So, we bring them by bus to Stratford, partner with the festival, and provide a whole new lens for them to see the world through. It’s an incredible experience just to walk by the river and have lunch outside – things these girls don’t typically get to enjoy in their own neighbourhood.”

Dr. Donna Ferguson

Dr. Donna FergusonFebruary is Black History Month, and the CPA is spotlighting contemporary Black psychologists throughout the month. Dr. Donna Ferguson is a clinical psychologist in CAMH’s Work Stress and Health Program and also runs a private practice where, among other things, she does refugee and humanitarian assessments.

“It’s nice when we hear back from some lawyers who say our report really made a difference in this case.”

It’s rare that a lawyer will reach out to Dr. Donna Ferguson to give her an update of any kind. But when they do it’s a great feeling because she knows she’s made a difference for a refugee seeking asylum in Canada. Dr. Ferguson is a clinical psychologist in CAMH's Work Stress and Health Program and also runs a private practice where, among other things, she does refugee and humanitarian assessments. She says,

“A lawyer may have a client who’s here from their country of origin, where they may have experienced trauma. Sometimes at the hands of a spouse or partner, or it could be bigger than that – it could be political violence. They might be fearful for their lives. Part of their refugee claim might be to have a psychological assessment to establish a diagnosis.”

The diagnosis from Dr. Ferguson and her team is not deciding whether or not a person stays in Canada, or whether their claim of refugee status is legitimate. They are not functioning as some kind of lie-detector test that one might see in the movies. Rather, they’re assessing a person and making recommendations based on what that person has been through, and what they might experience in the future.

“If there is a diagnosis of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) for example, we would build a case to say how it happened and if possible, get them into treatment here. And we can say that if they were to be sent back to their country of origin, they would have an exacerbation of those symptoms, and we would make recommendations around that.”

During the pandemic, these assessments are happening more rarely – doing them over virtual platforms has proven to be difficult, especially when a translator has to be added to the mix. During this time, Dr. Ferguson has found herself focused more on her job at CAMH, where she has found herself moving away from her original speciality, gambling addiction, and more into the space of workplace mental health.

“I do a lot of panels for CAMH as the Workplace Mental Health Person, giving advice to business leaders. We do Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) work, and those are the primary clients we see. Over the past 20 years I’ve got to know a lot about the workplace! The dos and the don’ts in terms of what business leaders should be doing for their employees, and how to keep people well at work.”

Again though, the pandemic has thrown a bit of a wrench into that. Years of learning the ins and outs of business culture, the best practices, and crunching the data from all kinds of studies has not prepared anyone for the sudden shift to a virtual business operation.

“A lot of this is a work in progress. People had to get creative really quick when it came to the pandemic, to build a virtual environment. CAMH has done it in a lot of ways – our program is fully virtually functional. We rebuilt our assessment tools to be virtual, our individual and group treatment programs, and all of our meetings became virtual. CAMH as a whole, and not just our program, has really done a lot virtually, and that knowledge has been instrumental in helping other organizations.”

Whether helping businesses with a longstanding culture adjust to pandemic life while looking after the mental health of their employees, or helping people from a vastly different culture find assistance here in Canada, Dr. Ferguson’s plate remains full. And the work, no matter what form it takes, remains rewarding!

Dr. Kofi-Len Belfon

Dr. Kofi-Len BelfonFebruary is Black History Month, and the CPA is spotlighting contemporary Black psychologists throughout the month. Dr. Kofi-Len Belfon is a clinical psychologist who works with children, adolescents and families. He wears many hats, one of them being as the Associate Clinical Director at Kinark Child and Family Services.

“Are we actually thinking about programming itself in an anti-oppressive way? Are we considering the content?”

Dr. Kofi Belfon is a clinical psychologist who works with children, adolescents and families. He’s the Associate Clinical Director at Kinark Child and Family Services, has a private practice called Belfon Psychological Services, is a member of the board of trustees for Strong Minds Strong Kids (formerly the Psychology Foundation of Canada), and sits on the Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) Committee at the College of Psychologists of Ontario. He is a measured speaker, and thinks carefully about his answers to every question. The theme of “thinking” comes up quite often in our conversation.

Born in St. Lucia, Dr. Belfon immigrated to Canada when he was about five years old. His family moved to live in the Caribbean when he was about 15, and he stayed with friends of the family to finish high school in Canada. His parents emphasized education, and encouraged him to go to university. His brother is a physician, and at first he went to McMaster for his undergrad intending to follow the same path and become a medical doctor. Soon though, he discovered that not only did he do extremely well in his psychology classes, he really enjoyed them. A new career path beckoned.

After his undergrad, Dr. Belfon went to work at a paint factory. While there, he wrote his GRE test (Graduate Records Examination – a general, standardized test to measure graduates’ academic abilities) and applied to grad school for psychology. What he didn’t do, which may have made a difference, was take the specific GRE exam for psychology. Every grad school rejected his application – every school but one.

“The only place I got in was Guelph. I had a really great supportive, nurturing supervisor in Dr. Michael Grand. But I always had this sort of impostor syndrome, doubting myself. ‘I didn’t get in anywhere else, why did I get in here, are they just trying to fill a quota? Am I getting in because I’m Black and male and they want to increase the diversity in their program?’ I had all these doubts about myself and they lingered for a long time. It was a fairly small cohort, maybe five or six of us, and I was the only one without a scholarship. I applied year after year, and never got a scholarship, and that fueled some of that imposter syndrome and the feeling I didn’t belong.

The silver lining for me was a couple of things – one, it forced me to work because I didn’t have a lot of money! I worked a ton in the field. I worked at the Toronto District School Board throughout my PhD and I got a lot of experience doing that. I worked at a private practice, I worked at Syl Apps Youth Centre, and I got lots of really neat clinical experience. I was also always really happy about my research. One of the things I appreciated about Dr. Grand was that he didn’t get in the way of me doing what I wanted to do.

My research was in chronic community violence in the Scarborough region, and then for my PhD it was about the mental health needs of kids in custody and detention. At the time at least 50% of those kids I was working with were BIPOC. Some of that research was because in university I had a close friend who died as a result of gun violence. That was the impetus for me starting that research, and even today I wish I had more time to do research and that sort of thing because it really means a lot to me.”

With all the different positions Dr. Belfon holds, and all the hats he wears, there is precious little time for research – or anything else for that matter. Especially now, when he says the pandemic has increased the workload significantly. Wait lists are getting longer and longer, and more and more children, youth, and families are reaching out for mental health help. He says this increase in demand predates the pandemic. Anecdotally, he says he’s seen more young people seeking help for depression, anxiety, and mental health disorders over the past five years. It’s not clear whether that is because more youth are suffering, or because work to destigmatize these conditions has made them more willing to reach out for help.

Those who reach out to Dr. Belfon are often Black families who are looking to connect with a psychologist who looks like them, and presumably shares many of their experiences. Often, they are willing to wait for a very long time, more than eight months on occasion, in order to see a Black psychologist. He thinks this is not ideal – it’s a really long time to wait when you’re having serious difficulties, and there’s no guarantee that you will connect with a professional. As Dr. Belfon says, “we confound race and culture all the time”.

The rarity of Black psychologists remains a difficulty in communities of colour, and is keenly felt in Southern Ontario. At one point, Dr. Belfon says, he thinks Belfon Psychological Services employed 60% of the Black psychologists in the region – there were three of them. Another reason EDI is so important going forward in the field of psychology.

He brings an EDI lens to all his ventures, working to make programming more inclusive at Strong Minds Strong Kids, at Kinark, and in his own practice. Dr. Belfon says that it’s good to make an effort to use more inclusive language, and to choose images and examples that feature a more diverse group of people. These things are helpful in terms of access, and get more people through the door. But doing those things are still ‘on the surface’. Once you get people through the door, is the programming itself delivering for their needs? Is the program they’re accessing as inclusive as the messaging that brought them there in the first place?

“I don’t necessarily know what the answers to that are going to be. These are still early days for psychology in thinking this way. But we need to evaluate these things while thinking about diversity, and how different families might think about these things differently. For example, a parenting program where we’re talking about parenting practices and what we view in North America as healthy practices. That might be totally different for a family whose parents didn’t grow up in North American society and maybe don’t hold the same types of values.”

This is when Dr. Belfon comes back to the theme of ‘thinking’ – what matters most in Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion efforts is that they are top of mind when a program is designed, a committee is set up, or a policy is implemented. If we all start to look at those things through an EDI lens, and start from that place, it is more likely that the end result will be truly inclusive and more than window-dressing.

“We think systematically in agencies, about all the inward-facing things. Executive structures, hiring practices, policies and procedures, thinking about how we treat one another. Maybe we’ve changed some language, and done a better job with basic stuff like not having binary language related to gender on our forms. Once we establish a framework with those sorts of things – and we’re doing some of that work at Kinark right now – the next step should be getting down to the actual clinical practice, and thinking about that more carefully. That will take some time, and maybe nothing changes! Maybe we look at a program and decide ‘the content is what the content is’. But did we think about it? Did we think about whether the content is relevant or not, instead of assuming that all these constructs are culture-neutral? I think that matters a lot.”

With the College of Psychologists of Ontario, the EDI committee is not on an island, but is rather a group of people who are there to influence all the other groups that can benefit from their input. Dr. Donna Ferguson is the Chair of the committee, and Dr. Belfon is working with her and the others to make EDI part of the overall culture at the College.

“We’ve done some work learning about the experiences our membership has had with EDI and the college, starting off with some questionnaires and collecting some data from the membership. We’ve done some training in EDI with the other committees – like discipline, quality assurance, my own committee which is Client Relations – so we have some language with which to think about EDI as a starting point. What we’ve asked is that following that training, members on those committees are challenged to think about how EDI might be related to their work.”

Dr. Belfon, Dr. Ferguson and the rest of the EDI committee are going to each other committee, one by one, to discuss how EDI is related to their work.

“For example, if the registration committee is responsible for our oral exams, in the oral exams are there things we have to be thinking about from an anti-oppression or inclusion perspective that might have to be rethought?”

Thinking. It is the central theme of everything Dr. Belfon does – and it is the key to moving organizations, companies, groups, and even psychology itself in a more inclusive direction. It’s all well and good to do something – but before you did, did you think about it? Did you consider it through the lens of inclusion? And how are you ensuring that your programming is inclusive, rather than just looking inclusive?

It’s something worth thinking about.

Dr. Monnica Williams

Dr. Monnica WilliamsFebruary is Black History Month, and the CPA is spotlighting contemporary Black psychologists throughout the month. Dr. Monnica Williams is a researcher at the University of Ottawa, dedicated to making research more inclusive for people of colour. In particular, at the moment, research into psychedelic medicine.

Dr. Monnica Williams is a therapist, author, and researcher at the University of Ottawa (among many others in a very long list of credentials). She has a long history of advocacy, activism, and social justice work, and has specialized in racial disparities in health, research, and elsewhere. An expert in anxiety disorders, she is currently one of very few researchers focused on the inclusion of people of color in psychedelic medicine.

“A lot of my research has been around the experience of trauma, and particularly trauma for racialized people – trauma that comes about from experiences of racism, and how we can best help people who are suffering. When it came to my attention 6 or 7 years ago that this research was going on into MDMA for the treatment of PTSD, I was really interested. Number one – does it work? Looking at the clinical trials and the research that was coming out it seemed to be very effective. And number two – will it work for people of colour? It was quite clear that while the research was promising, it was not inclusive.

Seeing millions and millions of dollars being poured into this novel treatment approach, which I think is really going to be a game-changer for mental health, and at the same time realizing that people a colour aren’t a part of it, that made me concerned – a little angry, actually. This is good enough for white people, why aren’t we getting any of it?

So I set out to research this so we could quantify the degree of exclusion we were experiencing. I was also hoping this could act as a call to action – to bring awareness to the fact that we need to be included and our voices need to be heard, and that treatment approaches have to be tailored to our communities. Not just what we might think of as a generic white middle class client, but there’s a whole spectrum of people who might benefit from these treatments.

It’s also important to note that not only have a lot of these psychedelic medicines been stolen from Indigenous cultures, and some of the methods have been stolen from Indigenous cultures as well. So we have to be cognizant of that when we approach this research.”

Dr. Williams has long been an advocate for inclusivity in research. For too long, people of colour have been excluded from research of all kinds, notably in a variety of psychological fields.

“So much of the research we see is exclusionary, and it not only perpetuates the problem but it’s also a symptom of the problem. Part of the issue is that we don’t have enough researchers of colour to do the research for people of colour. Certainly, there are a lot of white people who do research on these populations, but we have to be included too. As the saying goes, ‘nothing about us without us’. So the research community has to represent us, and we have to be included in it.

One of the big things that I’m advocating is more inclusion – opening the doors to our educational establishments to therapists of colour, and underscoring the need for us to be included. I also do a lot of research bringing these issues to light – how treatments might need to be adapted for people of colour, how therapists who are getting trained now can learn more about how to treat people with a more inclusive lens. Even the few therapists of colour who are coming through are being taught how to treat white people. So everybody needs to understand best practices when working with race, ethnicity, and across cultures.”

Dr. Williams says that through school and afterward she was unable to find a Black mentor in her institution, and for this reason it’s very important to her to mentor as many students as she can who find themselves in the same position as she was in school.

“I do a lot of mentoring of students of colour, because I have not had that kind of mentorship. When I was a junior psychologist, when I was first starting out, the person who was supposed to be mentoring me was actually quite abusive. So I went outside the institution and found my own mentors in the Delaware Valley Association of Black Psychologists. I worked with someone there, and it was good – it wasn’t exactly a fit in terms of the work that I did and the things they did – but I was just so happy to have Black people who were supporting me, encouraging me, and who believed in me. It was so different from my actual environment, and that made a big difference.”

Unfortunately, to this day not every institution has an environment that is inclusive of Black students or professionals. This is why Monnica turned elsewhere when she was a junior psychologist, and it’s why people of colour often look to turn elsewhere today. Creating those inclusive spaces is part of her life’s work, and something toward which the rest of Canada – in institutions and out – can strive.

Dr. Jude Mary Cénat

Dr. Jude Mary CénatFebruary is Black History Month, and the CPA is spotlighting contemporary Black psychologists throughout the month. Dr. Jude Mary Cénat is the director of the Vulnerability, Trauma, Resilience and Culture Research Laboratory (V-TRaC Lab), and the director of the Interdisciplinary Centre for Black Health.

“What field can be more anti-racist than psychology? We are here to promote human beings, human development, and human well-being! There is no field that can address racial issues better than psychology.”

Dr. Jude Mary Cénat is passionate about making psychology anti-racist, and inviting his colleagues in the mental health field to join the movement. Dr. Cénat is an Associate Professor in the school of Psychology at the University of Ottawa, the director of the Vulnerability, Trauma, Resilience and Culture Research Laboratory (V-TRaC Lab), and the director of the Interdisciplinary Centre for Black Health.

The V-TRaC Lab has three axes. The first is working on family, social, and cultural aspects of trauma and resilience. The second axis is global mental health – the lab has a project on different countries in Africa to document mental health problems related to infectious diseases like the Ebola virus and COVID-19. This axis also looks at gender-based violence and mental health in the Caribbean. The third concerns racial disparities in health and social services.

“We have some projects on Black mental health, and we conducted the first survey on Black mental health in Canada, as part of a major project funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada to document Black mental health and to develop and implement programs related to that. We are looking at the over-representation of Black children in the child welfare system to try to understand all the factors that create that situation and propose solutions.” In December 2021, The V-TRaC Lab revealed 13 recommendations to reduce the over-representation of Black children in the Child welfare system.

Involvement with child welfare is the number one predictor of youth ending up homeless, as well as for a multitude of other problems later on such as poverty and poor education. The over-representation of Black youth in that system means that they experience those outcomes more often than other groups, leading to a perpetual cycle

“The first factor is that professionals in the child welfare system are not trained to take into account the cultural aspects of Black families. We gather a lot of focus groups with stakeholders, and one of the things they point out is that they’re not trained enough to address cultural issues. We conducted a study that showed that more than 48% of social work programs in Universities and colleges in Ontario did not have a mandatory culture related course in 2020. There are also systemic factors such as poverty related to Black communities, and racial discrimination experienced by many in the child welfare system.

But it’s not just the child welfare system itself, it’s also the larger society. In schools, for example, teachers are more likely to call childrens’ protection services for an issue with a Black kid than they are with a white one. In Canada we have a ‘colourblind’ society, where we say ‘I don’t see your skin colour, I see your problems and I try to address those’. When you have a child with a problem in school, you can call the parents to address that. But often for white kids, teachers will address a problem directly with the parents, whereas they might call child welfare directly for a Black child.”

The idea of a ‘colourblind’ society is akin to having a ‘non-racist’ society. It is a passive way to approach race, where just not laughing at the racist joke, or not participating in a discriminatory hiring practice, is enough. But this does not go far enough in terms of redressing the racial inequities that already exist. Dr. Cénat hopes we can move beyond ‘non-racist’ and ‘colourblind’ to becoming a truly anti-racist society in Canada.

“As Ibram Kendi said, there is no ‘racist’ and ‘non-racist’. There is ‘racist’ and ‘anti-racist’. Because if you are just ‘non-racist’, you can see someone be racist, and you can satisfy yourself by telling yourself you’re not a part of it. You haven’t taken an action that can push back against racism. And only by taking action against racism can we create an anti-racist society.”

It is with this ethos in mind that Dr. Cénat and his team have created the course ‘How To Provide Antiracist Mental Health Care’, approved for Continuing Education credits by the CPA. If mental health practitioners, academics in higher learning institutions, and leaders across the country can embrace the principals of anti-racism, then we can truly start to move toward an inclusive Canada where everyone feels welcome, discrimination and profiling are not tolerated, and all of us share in the same opportunities on a level playing field.

Dr. Cénat published an article in The Lancet where he explained that anti-racist mental health care is proactive – in the sense that it addresses racial issues without waiting for clients or patients to bring these issues forward. Anti-racist care goes beyond cross-cultural care. It incorporates both cultural aspects and elements that provide a way to account for the damage caused by racial discrimination, racial profiling, and racial microaggressions. It is a way to create spaces in a society free of racism.

“The problem with the ‘colourblind’ approach is this. You might have someone in your office who is Black, but you say ‘I don’t see his skin colour, I assess him and provide care without seeing his skin colour.’ But the fact is that his skin colour might be a part of his problem. You might have a Black man who’s depressed, and one of the factors which explains that depression is the racial discrimination he experiences at work. Or because his children are experiencing discrimination and he does not have enough power to stand up for his children and that reminds him of the fact that as a kid he experienced the same discrimination from other children and teachers. When you say you don’t see his skin colour, you are not addressing his problem, because the colour of his skin is very much part of his problem.”

This is not just a hypothetical situation that might confront a mental health professional, it is backed up by data. Dr. Cénat’s team published an article that shows Black Canadians between the ages of 15-40 who experience high levels of racial discrimination are thirty-six times more likely to present with severe symptoms of depression than those who experience lower levels of discrimination.

“If you receive someone from the Black communities with depressive symptoms, you have to ask them about their experience with racial discrimination and trauma. So that is what our training ‘how to provide anti-racist mental health care’ provides to clinicians. To know how they can first learn about themselves and their own biases, then also how they can assess racial issues and trauma in a clinical practice. And how they can provide anti-racist care to children, adolescents, and families.”

From October 26-28 this year, Dr. Cénat and his team will be organizing the first conference dedicated solely to Black mental health. It will be called “Black Mental Health in Canada: Overcoming Obstacles, Bridging the Gap”. As Dr. Cénat says, no profession has greater tools to address racism than does psychology. And he’s committed to putting as many tools in that toolbox as he can.

Dr. Eleanor Gittens

Dr. Eleanor GittensDr. Eleanor Gittens is a professor at Georgian College in the Police Studies degree program. She helps students confront their biases before they graduate and go on to become police officers – by taking them to Barbados!

The national dish of Barbados is fried flying fish (try saying that six times fast) and cou-cou (a cornmeal-okra concoction) with a spiced gravy. Barbadian cuisine is also known as “Bajan” cuisine, and the fish cakes and fried delights have influenced food all over the globe. As with food, Barbados itself has had an outsized cultural impact compared to its tiny size. Barbados has a population of fewer than 300,000 people.

The town of Barrie, Ontario is, on its own, half the size of Barbados. It counts a little over 150,000 inhabitants, one of whom is Dr. Eleanor Gittens. Dr. Gittens was born in Barbados, and is now a professor at Georgian College in the Police Studies degree program. The key courses she teaches at the moment are in research methods, cyber crime, mental health issues in policing, and contemporary social movements. She says,

“My passion is research. I love to do research with policing agencies – especially if they have a question or concern but are unsure how to go about getting the evidence or the data from what they have already. I can help them answer those questions.”

One of those questions was regarding calls from local long-term care facilities in Orillia. The OPP service in the area approached Dr. Gittens because they were concerned that they were getting too many calls for service from those facilities that didn’t require police presence. Because research opportunities are also teaching opportunities, Dr. Gittens and a few of her students created a research team to examine the issue. They looked at all the calls over a period of time to determine what the evidence showed.

They found that the OPP were correct – that 60-70% of the calls they were getting from long-term care facilities did not require police presence. In many of the cases it was residents calling 9-1-1 directly from their rooms for something trivial like having misplaced their remote. Dr. Gittens and her students presented their findings to both the police service and to the long-term care facilities (and at the CPA Convention that year).

Their recommendations led to changes at both the police service and the care homes themselves. The long-term care organizations made changes to how their residents accessed telephones, and the processes by which staff contacted emergency services. The police changed policies beyond just when to respond, but also altered the way they responded to calls at these facilities to ensure the response was appropriate for the situation.

Most of the students who go through Dr. Gittens classes go on to become police officers. In recent years, a much greater focus has been placed on implicit bias in policing, and the ramifications that result from that implicit bias – most particularly, for communities of colour. Says Dr. Gittens,

“Often, police officers have a view of who the criminals are, and where the criminal activity takes place, based on their own personal biases and the feelings you’ve developed over time from working in the field. One of the things we’re trying to do when it comes to human rights and social justice is to break down some of those biases so that people can start to see things for what they are rather than seeing them through the lens of their bias.”

So how, then, to deconstruct some of that bias before these students graduate and go on to become police officers throughout Canada, serving vastly different communities with very different needs and systemic issues? Dr. Gittens says that although it is impossible to get rid of bias entirely, she figured the best way to move future officers in that direction would be to take her students – who are predominantly white – to a place where they would be the minority, removed from their current social environment. The students are in Orillia, a city with very little diversity. Dr. Gittens is the only Black professor at Georgian College. So where to take those students?

Barbados. She takes them to Barbados.

“Barbados is 95% Black. They get to explore the food, and the culture, and also to tour police stations and the prison. [Yes, there is only one prison in Barbados.] We’ve done a Supreme Court tour, where they got to sit in on a case. They got a chance to see some of the intricacies of how culture plays into peoples’ behaviour, how people think, and also how they are percieved. It’s only one opportunity for them, but I think it’s better than no opportunity at all.”

It’s hard to understand the impact of culture and heritage until you’re smack in the middle of one that is not your own. The students, of course, love these trips.

“Not only does every student love it, it’s one of the things police services are looking for now. When I have to do a reference for students going into policing, one of the questions they ask is ‘what do you know about their views on diversity?’ For the students I take on trips, I can speak to how they behaved during their visit. What set them apart from some of the other students? How did they embrace, for example, the food? There are people who refuse to try new food, simply because they don’t know it or understand it! Fear is an emotion that can really debilitate people.”

Dr. Gittens loves helping her students reach a higher level of cultural competency in her professional life, and loves to travel in her personal life. Unfortunately, the student trips, and her travel, have had to be put on hold to a large degree during the pandemic. One day, these things will be possible again. When they are, Dr. Gittens looks forward to bringing more students to Barbados to experience the culture, the atmosphere, and – of course – the cuisine. One word of advice to anyone who goes.

“Try the fish.”

Dr. Helen Ofosu

Dr. Helen OfosuDr. Helen Ofosu helps businesses move toward equity, diversity and inclusion as an Industrial/Organizational Psychologist. She says that employees of colour who are staying at home during the pandemic are realizing that their workplace may not have been a very welcoming one when they were there in person.

Dr. Helen Ofosu is an Industrial/Organizational psychologist, an Executive Coach and HR Consultant who founded I/O Advisory Services Inc. in Ottawa. She has extensive experience working with organizations and tackling structural racism at many levels.

“Generally speaking, I work with organizations – it could be government departments, private sector companies, or non-profits – often they bring me in to help with more inclusive hiring or to help improve their workplace culture. Over the past couple of years, I’ve done a lot more training in terms of equity, diversity, and inclusion with a splash of anti-racism and anti-oppression mixed in.

This winter what has me most excited is doing some work with a large government department on a mentorship program that’s quite different. We’re doing some training upfront with the mentors to make sure they understand some of the issues the racialized employees they’re trying to mentor have been experiencing. The idea is that with better awareness and understanding, mentors won’t be contributing to some of the issues with which racialized employees have been struggling. Equally important, with a more realistic perspective, the mentors can focus their interventions more effectively. It’s training for the mentors, but also offering some coaching for mentees above and beyond the support the mentors are providing.

Speaking more broadly, it’s all about supporting individuals and even organizations that are grappling with issues related to bullying, harassment, and of course various forms of discrimination.”

Dr. Ofosu has recently written and spoken about the “Great Resignation.” Over the past two years, during the pandemic, she has noticed a lot of racialized employees choosing to find work elsewhere, as they are realizing that while working from home, they are no longer subjected to the everyday indignities they experienced in the physical workplace.

“These things have been happening for years, but now people are removed from that environment, and they have the peace of mind that comes from doing their work without worrying about microaggressions, or getting the side-eye, or being excluded from coffees, lunches and conversations. When all of that is gone, people feel so much more relaxed because they can just focus on doing their work.

I think the real trigger was in the summer of 2022, when a lot of organizations were planning their return to work. It was only when people started to realize ‘oh my goodness – I might have to go back to the office’ that they started thinking ‘wait a second – I don’t think I can go back to the office. I don’t want to go back to the office! I don’t want to go back to the way things were.’

During all that reconsideration, a lot of people figured it was a smart time for them to find a different place to work, where there’s more representation, more inclusion, more diversity, and just a better workplace culture. From what I’ve seen, people are reflecting on a lot of things during the pandemic. So, they’re looking for a way to find employment where they can just be themselves, and focus on work instead of focusing on self-protection from all these emotional assaults.”

To some extent, Dr. Ofosu is shielded from this kind of thing, personally, by being self-employed. It is a good thing that she will be continuing to do her job, as she is one of very few Black psychologists doing this work in this space – work that is more top of mind than ever, and is more important and impactful now than it has ever been.

Charles Henry Turner

Charles Henry TurnerCharles Henry Turner was a zoologist, one of the first 3 Black men to earn a PhD from Chicago University. Despite being denied access to laboratories, research libraries, and more, his extensive research was part of a movement that became the field of comparative psychology.

Dr. Turner was a civil rights advocate in St. Louis, publishing papers on the subject beginning in 1897. He suggested education as the best means of combatting racism, and believed in what would now be called a ‘comparative psychology’ approach.

Charles Henry Turner was a zoologist, one of the first 3 Black men to earn a PhD from Chicago University. He became the first person to determine insects can distinguish pitch. He also determined that social insects, like cockroaches, can learn by trial and error.

Despite an impressive academic record, Dr. Turner was unable to find work at major American universities. He published dozens of papers, including three in the journal 'Science', while working as a high school science teacher in St. Louis.

Despite being denied access to laboratories, research libraries, and more, his extensive research was part of a movement that became the field of comparative psychology.

Dr. Turner was a civil rights advocate in St. Louis, publishing papers on the subject beginning in 1897. He suggested education as the best means of combatting racism, and believed in what would now be called a 'comparative psychology' approach. He retired from teaching in 1922, and died at the age of 56 on Valentine's Day in 1923.

Photo: biography.com

Keturah Whitehurst

Keturah WhitehurstA mentor to countless black psychologists, Keturah Whitehurst’s contributions to psychology extend beyond her own work to the work of her protégés that continues today.

Keturah Whitehurst was the first African-American woman to intern at the Harvard Psychological Clinic, and the first Black psychologist to be licensed in Virginia. She created the first counseling service at Virginia State College.

She received her Master's from the historically Black research university Howard in the 40s, and a PhD from Radcliffe in the 50s. She was a mentor to many future leaders in Black psychology - notably Aubrey Perry, who was the first Black person to graduate with a PhD in psychology from Florida State.

Dr. Whitehurst died in 2000, at the age of 88.

Photo from Kirsten's Psychology Blog

Dr. Olivia Hooker

Dr. Olivia HookerAs a psychologist, Dr. Olivia Hooker worked to change the unfair treatment inflicted upon inmates at a New York State women’s correctional facility. In 1963 she went to work at Fordham University as an APA Honours Psychology professor, and was an early director at the Kennedy Child Study Center in New York City.

Olivia Hooker was six years old when she lived through the 1921 Tulsa race massacre in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma. She went on to become the first Black woman in the US Coast Guard, joining during World War II in February of 1945. She later went back to the Coast Guard, joining the Auxiliary in Yonkers, NY at the age of 95 in 2010.

Her GI benefits allowed her to get a Masters from Columbia University, followed by a PhD in psychology at the University of Rochester.

As a psychologist, Hooker worked to change the unfair treatment inflicted upon inmates at a New York State women's correctional facility. In 1963 she went to work at Fordham University as an APA Honours Psychology professor, and was an early director at the Kennedy Child Study Center in New York City.

Honoured by the American Psychological Association, the Coast Guard, President Obama, and a Google Doodle, Olivia Hooker died in 2018 at the age of 103.

#BlackHistoryMonth

Inez Beverly Prosser

Inez Beverly ProsserInez Beverly Prosser was a Texas native who taught in segregated schools in the early 1900s. She travelled to the University of Cincinnati to obtain her doctorate in 1933, making her the first Black woman with a PhD in psychology.

Very little is known about Inez Beverly Prosser, a Texas native who taught in segregated schools in the early 1900s. Her state's universities were segregated, so she travelled to the University of Cincinnati to obtain her doctorate in 1933, making her the first Black woman with a PhD in psychology.

Sadly, Dr. Prosser was killed in a car accident a year after earning her PhD, but her dissertation was widely discussed for years afterward. She found that Black students in segregated schools had better mental health and social skills than those in integrated schools - in large part because of the prejudicial attitudes of the white teachers in those integrated schools. https://feministvoices.com/profiles/inez-beverly-prosser

Kenneth & Mamie Phipps Clark

Kenneth & Mamie Phipps ClarkFebruary is Black History Month and to celebrate and acknowledge the contributions that Black Psychologists have made to the discipline and the world, the CPA will be highlighting historically significant Black Psychologists throughout the month (#BlackHistoryMonth).