It has been more than 30 years since the Satanic Panic gripped popular culture. Millions were convinced there was an epidemic of child abuse stemming from satanic beliefs and rituals. There was no evidence to support these claims. There were TV specials, arrests, prosecutions, and even convictions – all based on something that never happened. Dr Randy Paterson joins Eric to look back at this phenomenon. He draws a parallel to today’s QAnon beliefs, and points out psychology’s role not only in explaining the panic in retrospect, but in fueling the flames in the first place.

Year: 2025

Is my dog angry or scared? Psychology and animal behaviour with Hannah Burrows

In this week’s episode of the Mind Full podcast we talk to Hannah Burrows, a Master’s psychology student specializing in animal behaviour. Specifically, the relationship between dogs and people. We talk about dogs, research, and the incredible things we have learned about animals over the years – crows, cuttlefish, and of course our own furry companions

CPAP Group Benefits Survey

The Council of Professional Associations of Psychology (CPAP), in collaboration with the Canadian Psychological Association (CPA), is seeking input on a potential group benefits plan for psychologists.

We ask that you please complete the brief survey below which asks whether you’re interested in a group benefits plan and if so, the coverage and features you would like offered/implemented.

English – https://web2.cpa.ca/membersurveys/index.php/415456?lang=en

French – https://web2.cpa.ca/membersurveys/index.php/415456?lang=fr

Thank you for taking the time to complete this survey.

PSYCHOLOGY WORKS Fact Sheet: Teens and Screens

Effects of Screen Use

It is well-known that screen use, and social media, are particularly interwoven into the lives of adolescents in modern society. Due to early access to smartphones, design features meant to keep youth on games and sites, and adolescents’ affinity for feedback from their peers, it is difficult to monitor their screen use and the impact on their mental health. Like younger children, teens who spend a great deal of time on screens tend to spend less time doing healthy activities that promote their development, such as socializing in-person, exercising, and reaching their academic potential. While technology provides access to helpful information, tools to get things done, and entertainment, it can also have a negative impact on teens. Here is a sample of some of the most common effects we have discovered so far:

- Social media can support connection and sense of community, particularly for youth who feel marginalized.

- Video game use can provide positive socialization and improve some cognitive skills.

- Excessive, problematic, or passive viewing such as scrolling, is associated with:

- symptoms of depression and/or anxiety

- reduced self-esteem

- sedentary lifestyle and possible weight gain

- distraction from school

- addictive use leading to increased interference with daily functioning such as getting enough sleep, eating well, and getting to school on-time

Recommendations for Use

Here are some recommendations to help reduce the likelihood of the negative effects of screen use. Remember, screen and social media use are developmental skills, like many other tasks of adolescence, your teen will make mistakes and need support to learn and grow in this area.

- First, watch for signs of problematic or excessive use. Examples of signs include:

- inability to put devices away or unplug

- not engaging with others in-person and/or social isolation

- not engaging in physical activities

- grades dropping or other signs of academic difficulties

- lying to get more access

- difficulty sleeping or reduced sleep

- Because of the serious effects of social media on many young adolescents’ mental health, it is critical to monitor their use of social media – protect from harmful and hateful behaviour.

- Due to positive social support and sense of connection, do not completely remove access to devices. Instead work towards setting age-appropriate limits both to content and amount of time on screens.

- As most adolescents are students, it is important to support them in their study habits. For example, teaching them to avoid “digital multi-tasking,” such as surfing while studying by placing their phone away from their study area.

Caregiver Strategies

It can be challenging to know how best to implement screen limits with teens. Here are some parenting strategies that can help:

- Role model healthy screen behaviour: Caregiver screen use is associated with child screen use and more negative effects.

- Have whole family, regular screen-free time: Everybody Unplug!

- Develop proactive structure and limits around screen use. Start when children are young.

- Teach adolescents social media literacy include who is safe to talk to and what is appropriate to post.

- Allow screen time only after completing other necessary tasks, for example, homework, physical activity, social activities.

- As teens display appropriate behaviour, provide intermittent periods of unsupervised access – with time limits and content monitored for young adolescents. Timing and tracking devices may be of use here.

- Do not extend the screen time in response to protests – validate their feelings of sadness and disappointment, coach them through regulating their emotions if upset and stick to the limit.

- Learn and practice emotion self-regulation strategies to cope with teen protests, for example, mindfulness, self-compassionate statements, and calm breathing.

- Teens may need to be reminded that screen and device access is a privilege, not a right and as the adult you are in charge and their well-being in your top priority.

- As older teens show ability to manage their screen use and literacy, more freedom is earned. Caregivers can gradually reduce content surveillance and screen time limit monitoring.

- Even with more freedom, check-in monthly to review the rules and how things are going. Praise youth for appropriate behaviour. If signs of problematic use emerge, time and content limits should be reinstated.

- Make sure to stay calm and approachable around discussing screen use so that teens feel comfortable to come to you if a mistake is made or a rule is broken. It is most helpful if teens come to you so you can problem-solve collaboratively how to move forward in a healthy way.

- Continue to monitor for signs of cyber-bullying as well as social exclusion. These may be similar to the signs of problematic or excessive screen use described above. Additional signs may include more serious mental health symptoms such as sudden changes to participation in activities, mood, and self-care. Similar to other times when your teen needs help, get involved in an active way, seek out mental health supports if needed, and work with your teen to set-up increased safety protocols using other strategies suggested here.

- Establish a safety and support protocol so that if they get into a risky situation or an incident occurs (much like “call home if you or your driver is unsafe to drive”) they will connect with you. This way your teen is able to get the timely support they need and problem-solve for the future, rather than hiding/making things worse due to fear of having phone/social media use removed.

- No screens in the bedroom/overnight (or ensure all notifications are turned off, and overnight usage monitored). Ideally all household electronics (parents too) go to a central location for charging overnight.

Additional Resources

We know that parenting around screen time and digital media use can be hard. Technology and programs are designed to be rewarding and make it hard to stop. Using these strategies will take time and practice but are worth the effort. Below are some additional resources to help. If you are concerned about the mental health and wellbeing of anyone in your family, please seek out additional professional support.

- Canadian Pediatric Society Digital Media Resources

- American Pediatric Society Family Media Plan

- Media Smarts: Canada’s Centre for Digital and Media Literacy

You can consult with a registered psychologist to find out if psychological interventions might be of help to you. Provincial, territorial, and some municipal associations of psychology may make available a referral list of practicing psychologists that can be searched for appropriate services. For the names and coordinates of provincial and territorial associations of psychology, go to https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/PTassociations/.

This fact sheet has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by Dr. Jo Ann Unger, C. Psych. and Dr. Michelle Warren, C. Psych., University of Manitoba.

Revised: May 2025

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the PSYCHOLOGY WORKS Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

References

American Psychological Association. (2023). Health advisory on social media use in adolescence. https://www.apa.org/topics/social-media-internet/health-advisory-adolescent-social-media-use

Boak, A., Elton-Marshall, T., & Hamilton, H.A. (2022). The well-being of Ontario students: Findings from the 2021 Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey (OSDUHS). Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/pdf—osduhs/2021-osduhs-report-pdf.pdf

Boers, E., Afzali, M.H., Newton, N., & Conrod, P. (2019). Association of screen time and depression in adolescence. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(9), 853-859. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1759

Boer, M., Stevens, G. W.J.M., Finkenauer, C., de Looze, M. E., & van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M. (2021). Social media use intensity, social media use problems, and mental health among adolescents: Investigating directionality and mediating processes. Computers in Human Behaviour, 116, Article 106645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106645

Kim, S., Favotto, L., Halladay, J., Wang, L., Boyle, M.H., Georgiades, K. (2020). Differential associations between passive and active forms of screen time and adolescent mood and anxiety disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(11), 1469-1478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01833-9

Li, X., Vanderloo, L.M., Keown-Stoneman, C.D.G., Cost, K.T., Charach, A., Maguire, J.L., Monga, S., Crosbie, J., Burton, C., Anagnostou, E., Georgiades, S., Nicolson, R., Kelley, E., Ayub, M., Korczak, D.J., & Birken, C.S. (2021). Screen use and mental health symptoms in Canadian children and youth during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 4(12), Article e2140875. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40875

Li, X., Vanderloo, L.M., Maguire, J.L., Keown-Stoneman, C.D.G., Aglipay, M., Andersons, L.N., Cost, K.T., Charach, A., Vanderhout, S.M., & Birken, C.S. (2021). Public health preventive measures and child health behaviours during COVID-19: A cohort study. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 112, 831-842. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-021-00549-w

MediaSmarts. (2022). Young Canadians in a wireless world, phase IV: Life online. https://mediasmarts.ca/sites/default/files/publication-report/full/life-online-report-en-final-11-22.pdf

Ponti, M. (2023). Screen time and preschool children: Promoting health and development in a digital world. Canadian Pediatric Society Digital Health Task Force. https://cps.ca/en/documents/position/screen-time-and-preschool-children#ref14

Toombs, E., Mushquash, C.J., Mah, L., Short, K., Young, H., Cheng, C., Zhu, L., Strudwick, G., Birken, C., Hopkins, J., Korczak, D.J., Perkhun, A., & Born, K.B. (2022). Increased screen time for children and youth during the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. https://doi.org/10.47326/ocsat.2022.03.59.1.0

PSYCHOLOGY WORKS Fact Sheet: Young Kids and Screens

Effects of Screen Use

Children have access to and use technology and electronic devices more than ever before. While technology provides access to helpful information, tools to get things done, and fun entertainment, it can also have negative impacts, particularly for children. This can include replacing other activities needed for healthy growth and development and negatively impacting emotional and social well-being. Here is a sample of some of the most commonly found effects we have discovered so far:

- While live, dynamic interactions with caring adults are best for children’s development, age-appropriate educational media can also support language, reading, cognitive and social development.

- Technologies can be used to encourage and compliment physical activity and motor milestones.

- Although specific uses of digital technology can support some developmental tasks, too much or excessive use is associated with:

- language delays, lower cognitive abilities, and delayed reading skills

- reduced emotional self-regulation ability and behaviour problems

- social skills deficits

- poorer motor development

- poor sleep when viewed before bed

Recommendations for Use

Here are some recommendations to make sure kids are not over-exposed to screens, particularly during the early years of brain development:

- Under 2 Years: No Screen Time.

- 2-5 Years: Less Than 1 Hour per Day.

- Currently there are no specific published guidelines for amount of screen use for children over 5 years of age. It is commonly recommended by clinicians that school-aged children not exceed 1 hour of recreational screen time per school day and not over 2-3 hours per weekend day, with flexibility for age and ability level.

- Some provinces have implemented a “no personal device policy” at school. While research is pending on its effectiveness, this appears to be a useful policy and likely helpful for elementary school-aged children’s overall development and well-being.

- Short periods of use broken up by whole body movement activities.

- Avoid screens after 7pm and at least 1 hour before bed.

- Prioritize educational, age-appropriate, and interactive material – no violent content for younger children. For older children, violent content should be monitored and debriefed with parents.

- Caregivers be present and engaged while young children are using digital media. This allows for active supervision as well as an opportunity to spend time with and get to know the interests of your children.

- Turn off screens when not in use. Passive screen use (e.g., TV’s on in the background) has been found to be associated with more negative effects of screen use as described above.

Caregiver Strategies

It can be challenging to know how best to implement screen limits with children. Here are some parenting strategies that can help:

- Role model healthy screen behaviour: Caregiver screen use is associated with child screen use and more negative effects for children.

- Have whole family, regular screen-free time: Everybody Unplug!

- Develop proactive structure and limits around screen use. Timing and tracking devices may be of use here. Start when children are young.

- Plan ahead for when children will get screen time, so you do not have to decide every time they ask.

- Understand your child’s screen activity so that you can support them in ending well. Can it be saved at certain points? Does a video length go beyond their time limit? Help them chose the screen activity and be specific around the type of media activity they will use, for example, “surfing” is harder to end and supervise.

- Prioritize screen activities that have positive benefits, such as educational apps and video connections with loved ones.

- Allow screen time only after completing other needed tasks, for example, homework, physical activity, social activities.

- Give a time warning before ending screen time so they can prepare to end or save their activity.

- Do not extend the screen time in response to protests – validate their feelings of sadness and disappointment, coach them through regulating their emotions if upset and stick to the limit.

- Learn and practice emotion self-regulation strategies to cope with child protests, for example, mindfulness, self-compassionate statements, and calm breathing.

- Have an activity or task ready to move to after the screen time has ended and gently guide them to it.

- Reward children with praise when they end screen time at the first request.

- If children act out when screen time ends, have a natural consequence prepared which the children know about ahead of time.

- For older children who have been allowed to engage with social media, require that they include you in their “friend” groups and allow you to follow them. This can be explained as part of your job in keeping them safe.

- For older children who have been allowed to participate in group chats, they need to allow random caregiver checks on content to ensure their safety and that they are learning to engage with friends online appropriately. While children may need more teaching, restrictions, and/or supervision if mistakes are made, make sure to stay calm and approachable around these discussions. It is most helpful if your older children come to you so you can problem-solve collaboratively how to move forward in a positive way.

- Additional strategies for monitoring and managing cyber-bulling risk factors for older children can be found on the Teens and Screens Fact Sheet.

Additional Resources

We know that parenting around screen time and digital media use can be hard. Technology and programs are designed to be rewarding and make it hard to stop. Using these strategies will take time and practice but are worth the effort. Below are some additional resources to help. If you are concerned about the mental health and wellbeing of anyone in your family, please seek out additional professional support.

- Canadian Pediatric Society Digital Media Resources

- American Pediatric Society Family Media Plan

- Age-Appropriate Viewing

- Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep: For Children Under 5 Years of Age

- Media Smarts: Canada’s Centre for Digital and Media Literacy

You can consult with a registered psychologist to find out if psychological interventions might be of help to you. Provincial, territorial, and some municipal associations of psychology may make available a referral list of practicing psychologists that can be searched for appropriate services. For the names and coordinates of provincial and territorial associations of psychology, go to https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/PTassociations/.

This fact sheet has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by Dr. Jo Ann Unger, C. Psych. and Dr. Michelle Warren, C. Psych., University of Manitoba.

Revised: May 2025

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the PSYCHOLOGY WORKS Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

References

Cost, K.T., Unternaehrer, E., Tsujimoto, K., Vanderloo, L.L., Birken, C.S., Maguire, J.L., Szatmari, P., Charach, A. (2023). Patterns of parent screen use, child screen time, and child socio-emotional problems at 5 years. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 35(7), Article e13246. https://doi.org/10.1111/jne.13246

Farah, R., Zivan, M., Niv, L., Havron, N., Hutton, J., & Horowitz-Kraus, T. (2021). High screen use by children aged 12-36 months during the first COVID-19 lockdown was associated with parental stress and screen us. Acta Pediatrica, 110(10), 2808-2809. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15979

Mantilla A., & Edwards, S. (2019). Digital technology use by and with young children: A systematic review for the statement on young children and digital technologies. Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 44(2), 182-195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939119832744

Ponti, M. (2023). Screen time and preschool children: Promoting health and development in a digital world. Canadian Pediatric Society Digital Health Task Force. https://cps.ca/en/documents/position/screen-time-and-preschool-children#ref14

Wong, R.S., Tung, K.T.S., Rao, N., Leung, C., Hui, A.N.N., Tso, W.W.Y., Fu, K.-W.Y., Jiang, F., Zhao, J., & Ip. P. (2020). Parent technology use, parent-child interaction, child screen time, and child psychosocial problems among disadvantaged families. The Journal of Pediatrics, 226, 258-265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.07.006

The CPA’s Scientific Affairs Committee is Seeking New Members!

The Canadian Psychological Association’s Scientific Affairs Committee (SAC) is currently recruiting new members. The SAC’s primary aim is to advance psychological science by working on matters of importance to the psychological research community, CPA members and affiliates, and groups of researchers. It is also responsible for the policies and practices of the CPA’s journals and other publications.

Yearly activities of SAC members include reviewing student research grant applications, providing input on CPA journal matters (e.g., publishing agreements, open-access wording, publishing standards), and reviewing special issue proposals for the journals. Additional activities will come up throughout the term. For more information on the SAC, or to read the SAC Terms of Reference, click here.

If you are interested in joining the important work of the SAC, please send a letter of intent and updated CV to Dr. Lauren Thompson, CPA’s Science Director at science@cpa.ca. In your letter of intent, please specify whether your research falls primarily within the mandate of SSHRC, NSERC, or CIHR.

Celebrate EVERYTHING with Dr. Rehman Abdulrehman

Every time we get to celebrate something, we’re a little happier as a result. A promotion, a birthday, an unusually warm and sunny day in January. The fact is, there are hundreds of reasons for a celebration, but for some reason we don’t lean into them all. Dr. Rehman Abdulrehman has a radical idea – let’s celebrate EVERYTHING!

A virtual reality tour of a residential school with Dr. Iloradanon Efimoff and Dr. Katherine Starzyk

Dr. Katherine Starzyk and Dr. Iloradanon Efimoff created a virtual reality tour of a residential school. They collaborated with Survivors and computer scientists to see if a tour in this manner could change attitudes toward residential schools and reconciliation. Did it work? Well…kind of. But that doesn’t mean the study wasn’t worth doing! On today’s episode of Mind Full we discuss what they learned and how even disappointing results move science and understanding forward.

CPA’s 2025-2030 Strategic Plan

It is with great pleasure that the CPA’s Board of Directors releases the CPA’s 2025-2030 Strategic Plan.

The CPA’s Board wishes to thank all members, affiliates, and associates who took the time, whether as individuals or as part of a collective, to provide input as part of our open consultation and call for feedback. With the new Strategic Plan, we have refreshed the CPA’s Vision, Mission, and Strategic Priorities. More…

2024 Best Article Award, Canadian Psychology / Psychologie canadienne.

Congratulations to Heather K. Gower and Graham Gaine for their article, Ethics of psychotherapy rationing: A review of ethical and regulatory documents in Canadian professional psychology (2024, Vol. 65, Issue 1, pp. 15-27) which was selected as the winner of the 2024 Best Article Award in Canadian Psychology / Psychologie canadienne.

The CP Editorial team nominates articles for this award, and the articles are adjudicated by the CPA Board of Directors representing Science, Practice, and Education.

This article is now Free to Read, to access it, click here.

2024 Best Article Award, Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement

Congratulations to Scott Davies and Angran Li for their article, Effects of summer numeracy interventions among French-language students in Ontario (2024, Vol. 56, Issue 3, pp. 195-204) which was selected as the winner of the 2024 Best Article Award in the Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement.

The CJBS Editorial team nominates and adjudicates articles for this award.

This article is now Free to Read, to access it, click here.

The psychology of anti-trans legislation with Dr. Alison Phillips and Julia Standefer

We’ve spoken on Mind Full before about anti-trans legislation, and the push to sideline the scientists doing work in the sex and gender space. But we’ve always done so from a Canadian perspective. We were curious to know how American psychologists are feeling at the moment. Dr. Alison Phillips and Julia Standefer, researchers at Iowa State University, tell us about their current situation and a recent article.

2024 Best Article Award, Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology / Revue canadienne de psychologie expérimentale

Congratulations to Véronic Delage, Richard J. Daker, Geneviève Trudel, Ian M. Lyons, and Erin A. Maloney for their article, It is a “small world”: Relations between performance on five spatial tasks and five mathematical tasks in undergraduate students (2024, Vol. 78, Issue 4, pp. 256-274) which was selected as the winner of the 2024 Best Article Award in the Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology / Revue canadienne de psychologie expérimentale.

The CJEP Best Article Award is co-sponsored by the CPA and the Canadian Society for Brain, Behaviour and Cognitive Science (CSBBCS). The CJEP Editorial team nominates articles for this award, and the articles are adjudicated by CPA and CSBBCS appointed members.

This article is now Free to Read, to access it, click here.

Psychological Tele-Assessment: Guidelines for Canadian Psychologists

On December 17th, 2024, the CPA’s Board of Directors approved the Psychological Tele-Assessment: Guidelines for Canadian Psychologists.

For more information, or to download a copy of the guidelines, click here. (PDF)

CPA’s Indigenous Student Award: Scholarship in Psychology

The purpose of this program is to encourage and support Indigenous (Inuit, First Nations, or Métis) students in psychology in Canadian universities. This is an academic merit-based award that also takes into consideration life factors such as motivation to excel in the field of psychology and level of need in overcoming barriers to attending university.

Application requirements include official transcript, CV or resume, personal statement, and one letter of support.

This year, the CPA welcome applications for one (1) graduate scholarship. Eligible students must be:

- Indigenous;

- a CPA student affiliate in good standing at time of application, and if successful for the duration of the scholarship length; and

- entering graduate studies or be a current graduate student at a Canadian university.

Value of the scholarship is $4000.00 per year, renewable for up to five additional years.

CLOSED for 2025 – Deadline for applications is May 10th, 2025.

2025 Section Newsletter Award Winner

The Student Section is the winner of the CPA Section Newsletter Award for their Fall 2024 newsletter (PDF).

version francais (PDF)

The CPA recognizes the efforts that the Sections put into creating and maintaining their newsletters. Section newsletters serve as an important communication tool to help keep members informed and involved in the Section and in CPA.

Psychology, mental health, and the federal election with Glenn Brimacombe

Glenn Brimacombe is the CPA’s Director of Policy and Public Affairs, and a registered lobbyist. Glenn advocates for mental health funding and parity (to get mental health coverage on par with physical health coverage), and has some ideas about how to keep mental health at the forefront of the issues as an election looms.

CPA Responds to Canada Health Act Letter of Interpretation (March 2025)

In January 2025, the Federal Minister of Health issued a letter of interpretation on the Canada Health Act that identified certain regulated professions (nurse practitioners, midwives and pharmacists) as providing “physician equivalent services” and should be publicly insured by the provinces and territories. However, psychology was specifically not recognized, see CPA’s response.

The Friendship Guide with Dr. Jillian Roberts

Dr. Jillian Roberts is a Professor at the University of Victoria, a registered psychologist in B.C., and an author who has written a string of successful children’s books in the Just Enough and The World Around Us series. Her latest book, The Friendship Guide, is a book that helps kids learn how to make friends and how to be a good friend.

Release of CPA Policy Primers (February 2025)

Knowing that a federal election is around the corner, the CPA recognizes the importance and need to continue to invest in our collective mental health; which brings with it a number of health, social and economic dividends that benefit individuals, families, communities and the country as a whole. With the objective of contributing to the country’s public policy-making when it comes to mental health, the CPA has developed a policy primer entitled The Federal Government & Mental Health Policy…Preparing for the Next Federal Election. The CPA has focused on a select number of policy issues where the federal government can play a strong leadership role: (1) improving and expanding publicly funded access to psychological services; (2) improving employer-based coverage for psychological services; (3) increasing the number of practicing clinical psychologists, and (4) increasing investment in psychological research.

CAMIMH Releases 3rd Annual Mental Health-Substance Use Health Report Card (January 2025)

The Canadian Alliance on Mental Illness and Mental Health (CAMIMH) released it 3rd annual mental health-substance use health report card. It is clear that there remains a gap between what the people of Canada expect from their governments and what they are delivering. More must be done to ensure people in need of support for their mental health and substance use health get the care they need, when they need it. See news release and survey.

Psychology Month Profile: Liisa Galea

Liisa Galea

Dr. Liisa Galea is a scientific lead for the CAMH (the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health) program womenmind™. It’s a community of philanthropists, thought leaders and scientists dedicated to tackling gender disparities in science, and to put the unique needs and experiences of women at the forefront of mental health research.

Psychology Month 2025: Knowledge mobilization and video interviews with Madeline Springle

Madeline Springle is a second-year Ph.D. student at the University of Calgary, who is winning awards for her ability to mobilize knowledge. Specifically, she is taking the research she has done into one-way video interviews, and using it to help people who might use this knowledge to better prepare for their own job search.

As we close out Psychology Month, we wanted to highlight knowledge translation (explaining the science for a more general audience) and knowledge mobilization (putting new findings into practice such that they help those they were designed to help) because without those, science exists in a vacuum!

Fall 2024 Newsletter of the CPA Section for Students

Dear Students,

We are very happy to distribute the Fall Newsletter of the CPA Section for Students. CPA Student Newsletter, Fall 2024

Kind regards,

The CPA Student Section Executive Team

CPA signs Global Psychology Alliance (GPA) Democratic Systems and Psychological Science Statement and Call to Action

The CPA has signed a statement published by the GPA, Democratic Systems and Psychological Science: A Collective Statement and Call to Action. The members of the GPA have recognized the profound impact of social and political determinants on mental health and call upon psychologists worldwide to advocate for the protection and promotion of democratic systems as a means to enhance health globally.

PSYCHOLOGY WORKS Fact Sheet: Narcissism

What is Narcissism?

Narcissism is part of an individual’s personality organization and is the way people maintain a positive self-image, regulate their self-esteem, and manage their needs for affirmation and validation from others. It is normal for people to possess a healthy amount of self-esteem where they are accepting of their strengths and limitations while maintaining a positive self-image. It is normal and healthy for individuals to seek adaptive and realistic ways to improve their self-concept and feel good about who they are.

Clinical narcissism, on the other hand, reflects unhealthy strategies to cope with disappointments and threats to positive self-image. Persistent difficulty in this area is what typically constitutes a clinical diagnosis of narcissistic personality disorder (NPD). Clinicians diagnose NPD when a person meets 5 or more of the following DSM-5 criteria:

- A grandiose sense of self-importance

- Preoccupation with fantasies of unlimited success, power, brilliance, beauty, or ideal love

- Beliefs of being special and unique

- A need for excessive admiration

- A sense of entitlement

- Taking advantage of others for personal gain

- A lack of empathy

- Arrogant and haughty behaviours or attitudes

How is Clinical Narcissism Expressed?

When we think of narcissism, we usually picture someone who displays narcissistic grandiosity, or a pattern of entitled, domineering, and attention-seeking behaviour. These traits align with certain aspects of NPD, including excessive self-enhancement strategies, diminished empathy, and a disagreeable demeanor. However, impairment in the ability to regulate the emotions and behaviours associated with one’s needs for self-enhancement is at the root of pathological narcissism – understood as narcissistic vulnerability. Narcissistic vulnerability is characterized by a fragile self-image and low self-esteem reliant on external validation. It involves heightened sensitivity to threats to self-concept, leading to anxiety, helplessness, persistent negative emotions, distrust of others, and social withdrawal. Clinical narcissists oscillate between states of grandiosity and vulnerability. As the two occur in tandem, there are no officially recognized subtypes of clinical narcissism or NPD.

The representation of narcissism in the DSM-5 has received scrutiny for describing primarily grandiose and overt manifestations while overlooking the important and inevitable vulnerable aspects. Recent research suggests that vulnerability can be conceptualized as “primary narcissism”, as internalised feelings of shame, low self-worth, and difficulty processing criticism or failure are at the core of all narcissistic behaviours. Genuine grandiosity that is not an attempt to conceal feelings of low self-worth may be better understood as a manifestation of psychopathy.[1]

Moreover, narcissism can be expressed overtly (i.e., behaviours, attitudes, and emotions) or covertly (i.e., internal cognitions, motives, needs, and feelings). People often incorrectly associate overt expressions with grandiosity and covert expressions with vulnerability. However, individuals with NPD tend to exhibit both overt and covert grandiose and vulnerable traits at different times or even simultaneously. For example, overtly arrogant behaviour can mask underlying feelings of inadequacy and vulnerability.

How Can We Identify Narcissism?

Recognizing the signs that someone may have narcissistic tendencies, regardless of severity, can help us understand and address them with empathy and accuracy.

Key characteristics of narcissism include:

- Self-perception and Emotional Regulation Challenges

- An exaggerated sense of self-importance, often coupled with feelings of insecurity, shame, or fear of being exposed as a failure.

- A relentless drive for perfection and external validation to uphold a fragile self-image.

- Extreme sensitivity to criticism or rejection, leading to defensive behaviours like withdrawal, aggression, or projection of blame.

- Interpersonal Challenges

- Decreased social inhibitions, allowing for displays of entitlement and unreasonable expectations for favourable treatment or recognition.

- Difficulty with empathy and valuing the needs and emotions of others, which may manifest as controlling, manipulative, or dismissive behaviours.

- Trouble maintaining friendships and relationships, leading to increased isolation over time.

- Emotional and Behavioural Dysregulation

- Persistent negative affectivity, such as depression, anxiety, or anhedonia, while often denying any feelings of depression or weakness.

- High emotional reactivity, including intense anger, embarrassment, jealousy, or mood instability, especially when self-enhancement and reassurance needs are unmet.

- Poor impulse control and increased thrill-seeking behaviour.

There are some complications that may arise with an NPD diagnosis that are important to be aware of:

- NPD can occur along with other conditions such as substance use disorders, mood and anxiety disorders, and other personality disorders. This can make it difficult to accurately diagnose NPD.

- A higher risk of death by suicide.

- A greater presence of hostility and aggression, increasing interpersonal difficulties and creating challenges with treatment.

What Are the Risk Factors for Developing NPD?

- Early childhood experiences including parental overvaluation, excessive admiration, praise, and beliefs that the child has exceptional abilities have been associated with narcissism in adulthood. Conversely, adverse experiences in early childhood including parental coldness, parental abuse, feeling rejected, and a fragile ego during childhood may also predict narcissism in adulthood.

- Narcissistic individuals may be genetically predisposed to developing the disorder.

- NPD is more likely to occur among individuals experiencing other personality disorders including antisocial personality disorder, histrionic personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, and schizotypal personality disorder.

- Research demonstrates that the prevalence of narcissism tends to be higher among young adults relative to older adults.

- NPD is typically more common among men than women, with research finding a lifetime prevalence of 7.7% in men and 4.8% in women.[2]

How Can You Support a Loved One with NPD?

Supporting a loved one with narcissism is a compassionate goal, but it can also be emotionally challenging. Here are some ways to provide support while prioritizing your own well-being:

- Educate yourself about NPD to understand the nuances of the disorder and possible treatment or symptom management options.

- Communicate to your loved one with NPD that you accept them. Remind yourself that their behaviours are a result of the pain they are experiencing due to their mental illness. Making them feel loved and supported can help guide them towards the proper treatment.

- Encourage your loved one to seek treatment but recognize that you cannot force change. While it can be frustrating if they are resistant to help, remember that their behaviour is their responsibility, not yours.

- Try to set and maintain healthy boundaries. Individuals with NPD may rely on others to meet their needs or expectations in ways that can feel overwhelming. Clearly express what you are willing and able to do and stay consistent in respecting your own limits.

- Make sure to take care of your own needs and mental health. Avoid letting your loved one’s disorder take over your life. Try your best to maintain other social connections and support systems. Consider attending therapy or joining a support group.

- People with NPD have an increased risk of suicide. If you notice signs of withdrawal or suspect your loved one is considering self-harm, address your concerns directly and compassionately. If they are in immediate danger, contact emergency services right away.

How Can Psychology Help?

There is no standardized treatment that exists for narcissism, but psychologists can help individuals with narcissism manage their symptoms with psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, or talk therapy, is a long-term approach to treatment focused on building a strong patient-therapist relationship.

- Transference-focused therapy (TFT) is a twice-weekly approach that focuses on the patient’s feelings towards the therapist. This method proposes that people with narcissism separate positive and negative self-perceptions as a defence mechanism. The goal is to help them understand their emotions and integrate these self-perceptions in a healthy way.

- Schema-focused therapy aims to help patients identify and adjust cognitive and behavioural patterns (i.e., schemas) that drive narcissistic traits. Narcissistic schemas, such as an inflated sense of self-importance, are enduring beliefs that develop early in life. This approach is especially useful for those who do not respond well to standard cognitive therapies.[3]

There are no medications currently available to treat personality disorders like NPD. However, many NPD patients benefit from the use of medications (e.g., antidepressants) to manage symptoms such as anxiety and depression.

In addition to treating those with NPD, psychologists play a critical role in supporting individuals affected by narcissistic behaviours, such as family members or friends. Psychoeducation can help these individuals understand the complexities of narcissism, set healthy boundaries, and develop effective coping strategies.

Psychologists can also continue to conduct research on narcissism to further our understanding and improve treatment approaches. By studying the underlying mechanisms and various expressions of narcissism, psychologists can refine existing therapeutic methods and develop new, evidence-based interventions tailored to individuals’ needs.

You can consult with a registered psychologist to find out if psychological interventions might be of help to you. Provincial, territorial, and some municipal associations of psychology may make available a referral list of practicing psychologists that can be searched for appropriate services. For the names and coordinates of provincial and territorial associations of psychology, go to https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/PTassociations/.

This fact sheet has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by Erin Vine, MA.

Revised: January 2025

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the PSYCHOLOGY WORKS Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

[1] Kowalchyk, M., Palmieri, H., Conte, E., & Wallisch, P. (2021). Narcissism through the lens of performative self-elevation. Personality and Individual Differences, 177, Article 110780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110780

[2] Stinson, F. S., Dawson, D. A., Goldstein, R. B., Chou, S. P., Huang, B., Smith, S. M., Ruan, W. J., Pulay, A. J., Saha, T. D., Pickering, R. P., & Grant, B. F. (2008). Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV narcissistic personality disorder: Results from the wave 2 national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(7), 1033-1045. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v69n0701

[3] Bernstein, D. P. (2005). Schema therapy for personality disorders. In S. Strack (Ed.), Handbook of personology and psychopathology (pp. 462-477). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=cdde7fb2a0b22decd35971ef82fd4473b1eb8837

Le Mois de la psychologie : la santé sexuelle avec Sophie Bergeron, Ph. D.

Cette semaine, dans le cadre du Mois de la psychologie dont le thème, cette année, est « Les femmes et la science », nous présentons Sophie Bergeron, Ph. D., qui détient une Chaire de recherche du Canada sur les relations intimes et le bien-être sexuel au Département de psychologie de l’Université de Montréal, où elle dirige également le Centre de recherche interdisciplinaire sur les problèmes conjugaux et les agressions sexuelles (CRIPCAS), l’Équipe SCOUP Sexualité et Couple, et le Laboratoire d’étude de la santé sexuelle. Ses travaux portent sur les déterminants psychosociaux de la santé sexuelle des individus et des couples ainsi que sur le traitement des dysfonctions sexuelles.

PSYCHOLOGY WORKS Fact Sheet: Family Building for Gender Diverse Individuals

Gender diverse individuals are those whose gender identity, expression, or experiences differ from traditional societal norms and expectations associated with the sex medical professionals assigned to them at birth (e.g., trans, nonbinary people). Family building for gender diverse individuals can be a complex and empowering journey, often enriched by diverse pathways and thoughtful considerations. Extending beyond traditional understandings of reproductive health, family building in this context encompasses a wide range of options such as biological conception, adoption, surrogacy, and fertility preservation. Gender diverse individuals seeking to build their families may face medical, legal, and social barriers, including access to inclusive healthcare, legal recognition of their gender and parental rights, and societal acceptance. Moreover, the intersection of trans, nonbinary, and gender expansive identities with other identities and societal power structures, such as race and racism, socioeconomic status and poverty, as well as disability and ableism, can further influence family building choices and experiences. It is important that healthcare providers, including psychologists, approach family building for anyone with sensitivity, inclusivity, and an understanding of the specific needs and challenges they may encounter. Approaching this work with humility by listening to the unique experiences and challenges of each person is essential. This approach ensures that gender diverse individuals are supported to make informed decisions about family building and their reproductive health.

What Factors Influence Family Building?

- Desire for Genetic Offspring: This desire varies among individuals. For some, the desire to have children who share their genetic makeup is very important. Having genetic offspring may not always be feasible due to various medical or biological constraints. Discussing these factors with health care providers is often important. Understanding these limitations is a part of the family building process and may involve experiences of loss and grief.

- Partner Factors: The dynamics of family building can vary significantly depending on whether one is planning to conceive alone or with a partner(s). In cases involving a partner(s), their age and reproductive capabilities are important considerations. For instance, a trans man or trans masc person wishing to conceive must consider whether their partner can biologically contribute viable sperm.

- Gender Dysphoria: The process of conceiving, including Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART), can exacerbate feelings of gender dysphoria (if present) for some individuals. Those undergoing Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) may need to temporarily discontinue their hormones for fertility preservation or conception purposes, potentially intensifying feelings of gender dysphoria. Seeking psychological support and engaging in self-reflection can help individuals make informed decisions and navigate complex emotions that may arise.

- Transitioning: Navigating transition may influence family building decisions. For example, if someone undergoes an orchiectomy (i.e., surgery to remove one or both testicles) without prior sperm preservation, their options for having genetically related children may become limited. Understanding and planning for their reproductive options if desired is essential early in someone’s transition.

- Financial Factors: The costs associated with fertility treatments, adoption, and fertility preservation are often substantial and not typically covered by provincial or private healthcare plans. However, some provinces (Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, and British Columbia) offer some government-funded options. Prospective parents are encouraged to research funding that may be available to them in their province. The financial burden can be a significant barrier to family building, necessitating careful planning and exploration of available financial support options.

- Cultural Factors: Cultural beliefs about family, reproduction, and gender roles can influence how individuals approach family-building, including the types of options they pursue or consider. For example, biological parenthood may be valued in a person’s culture, which may create additional pressure to preserve fertility or pursue options like surrogacy. Conversely, cultural norms that stigmatize gender diversity may result in limited family-building support within a person’s community or family of origin. Religious perspectives on reproduction, adoption, and assisted reproductive technologies (ART) can further intersect with gender identity, shaping both opportunities and challenges.

What Are Some Options for Family Building?

- Adoption: All people have the option to adopt, either within Canada or internationally. There can be complex legal and social landscapes to navigate, particularly in international adoption. Prospective parents are encouraged to seek supportive legal and psychological guidance, as well as community support, throughout the adoption process.

- Surrogacy: Surrogacy is an option for those desiring genetically related children who either have viable or preserved sperm or eggs. In surrogacy, an individual with a uterus carries the pregnancy for the intended parent(s). Canadian law permits gestational surrogacy as long as surrogates are reimbursed only for reasonable expenses. This arrangement requires careful legal and ethical considerations to ensure the rights and wellbeing of all parties involved are protected.

- Fertility Preservation: This is an option for those who wish to retain the possibility of having genetically related children in the future. Private fertility clinics typically perform this procedure. Options include:

- Sperm Cryopreservation: Involves collecting and freezing semen samples for future use. Some fertility clinics offer the option for surgical retrieval of sperm.

- Oocyte Cryopreservation: Involves stimulating the ovaries to produce multiple eggs, retrieving these eggs, and freezing them for future use.

- Ovarian Tissue Freezing: A newer technique where medical professionals remove and freeze ovarian tissue for later use. This tissue can potentially be transplanted back into the body to restore fertility, though it is a relatively novel and evolving method.

- Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART): These technologies assist individuals in conceiving a child using their own, their partner’s, or a donor’s reproductive material:

- Intrauterine Insemination (IUI): This procedure involves placing sperm directly into the uterus (of the intended parent or a surrogate) using a catheter, a less invasive and often less expensive option than In Vitro Fertilization (IVF).

- In Vitro Fertilization (IVF): IVF is a more complex set of procedures involving the retrieval of eggs (or using previously frozen eggs), fertilizing them with sperm in a laboratory setting, and then transferring the embryo(s) into a uterus (either of the intended parent or a surrogate). This method is often used when other fertility treatments have not been successful.

How Can Psychologists Help?

- Provide support and resources: Psychologists can provide emotional support and resources to their clients throughout the process of starting or expanding a family and help provide information on appropriate medical, legal, and community resources as needed.

- Address reproductive goals and concerns: Psychologists can work with clients to discuss their reproductive goals and concerns, providing support and guidance as they navigate the decision-making process around starting or expanding a family.

- Collaborate with allied professionals: Psychologists can work alongside allied health professionals, such as social workers, to ensure clients receive comprehensive, coordinated care that aligns with their family-building choices.

- Advocate for inclusive reproductive healthcare: Psychologists can advocate for clients’ rights to inclusive and affirming reproductive healthcare, and help clients navigate any discrimination or barriers they may face when accessing reproductive healthcare.

You can consult with a registered psychologist to find out if psychological interventions might be of help to you. Provincial, territorial, and some municipal associations of psychology may make available a referral list of practicing psychologists that can be searched for appropriate services. For the names and coordinates of provincial and territorial associations of psychology, go to https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/PTassociations/.

This fact sheet has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by Olivia Fischer, Lynn Corbett, Jesse Bosse, Keira Stockdale, Anita Shaw, and Jelena King.

Revised: December 2024

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the PSYCHOLOGY WORKS Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

Psychology Month 2025: Anxiety, gender, and leadership with Dr. Winny Shen

There has always been a stereotype that women are “more emotional” than men, and even that they are “too emotional” for leadership roles. Dr. Winny Shen joins Mind Full to discuss the results of her study which suggest that not only is that stereotype untrue, the exact opposite might actually be the case.

Psychology Month Profile: Jessica Strong

Jessica Strong

We all plan to get older. So why do so few of us gravitate toward working with older adults? Dr. Jessica Strong is a Geropsychologist in the department of psychology at the University of PEI. She tells us about cognitive reserve, fights against ageism, and discusses how a passion for music led her toward her current career path.

Psychology Month 2025: Bullying in school and society with Dr. Wendy Craig and Dr. Deinera Exner-Cortens

Psychology Month Profile: Laura Thomas

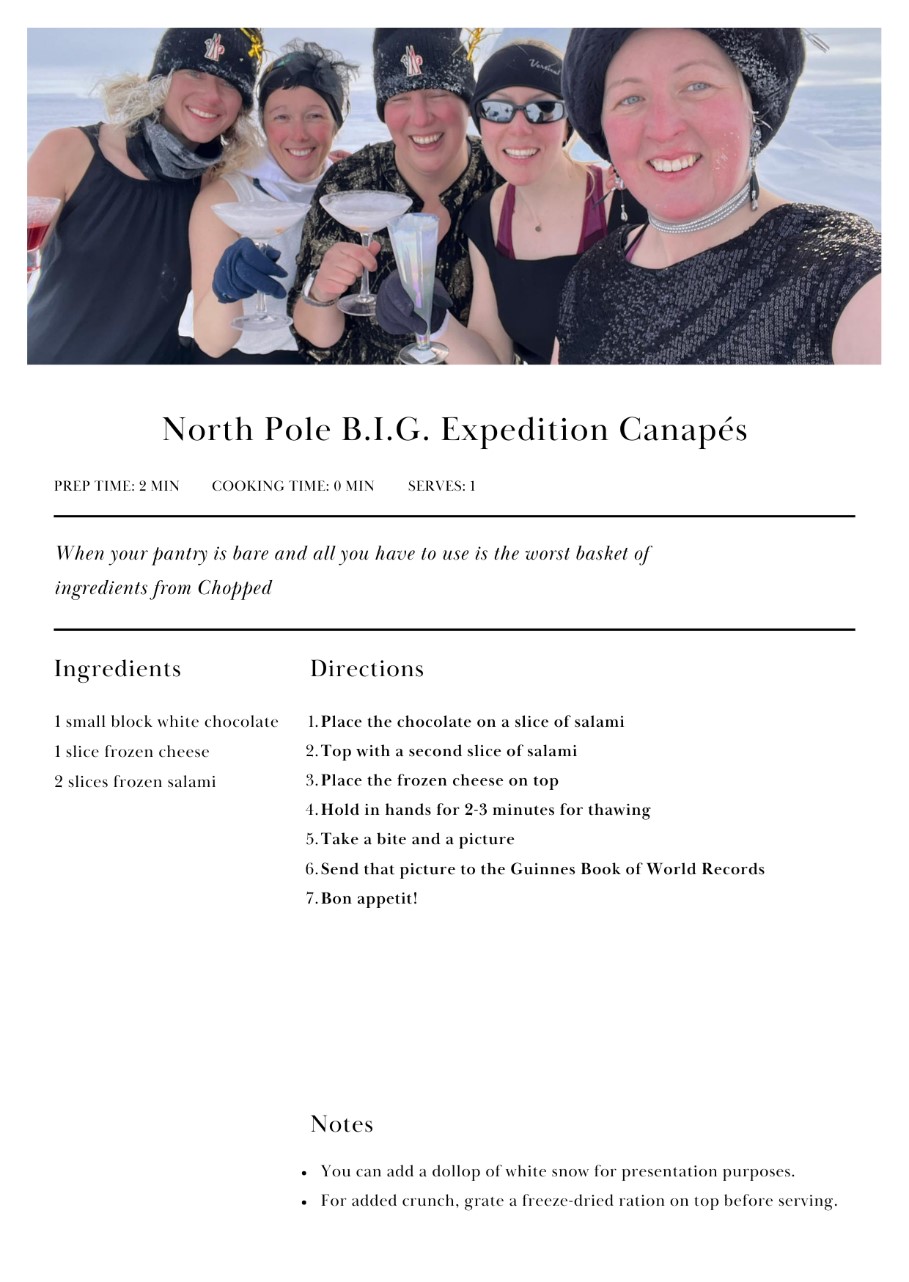

Laura Thomas-photo by Erik McRitchie

B.I.G. at the North Pole photo by Edel Kieran

Training astronauts for space flight requires a huge team, including psychologists who can help to prepare them for the close quarters and isolation for long periods of time. Laura Thomas is not only one of those psychologists, she has also experienced similar close quarters and isolation with all-female expeditions to places like the North Pole.

We kick off 2025’s Psychology Month: Women in Science with a look at Laura’s work, her travels, and the requirements for setting a Guinness World Record!

A PhD, a radio show, and now a children’s book with Sommer Knight

While completing her psychology PhD, Sommer Knight is busy putting everything she learns to use. She co-hosts a radio show and has now written a children’s book to advance the conversation about mental health in Black families and Black communities.

The book is called Today Is a Rainy Day, and if you’re in the Ottawa area Saturday March 1st, join Sommer and her co-authors and illustrator from 1-5pm at Indigo Rideau, 50 Rideau St, for a book signing event!

Why the CPA/CPAP BMS Insurance Liability Program Is Right For You

The CPA/CPAP Professional Liability & Commercial General Liability Insurance Program, brokered by BMS Canada Risk Services Ltd. (BMS), is the largest program of its kind for psychology practitioners in Canada with over 12,000 participants. From its market leading coverage to its broker support to its association advocacy, the program has protected CPA/CPAP members with specialized Liability Insurance for over 30 years. Learn more here.

The CPA/CPAP Professional Liability & Commercial General Liability Insurance Program, brokered by BMS Canada Risk Services Ltd. (BMS), is the largest program of its kind for psychology practitioners in Canada with over 12,000 participants. From its market leading coverage to its broker support to its association advocacy, the program has protected CPA/CPAP members with specialized Liability Insurance for over 30 years. Learn more here.

To purchase coverage, please visit www.psychology.bmsgroup.com, or contact a BMS broker at 1-855-318-6038 or by email at psy.insurance@bmsgroup.com.

- Why the CPA/CPAP Program Is Right For You (PDF)

- Comparing Professional Liability Insurance Policies (PDF)

- Frequently Asked Questions about the CPA/CPAP Program (PDF)

- What to do in the Event of a Claim (PDF)

- Professional Liability & Commercial General Liability Coverage Video

For more information about your Insurance Broker, BMS, and Insurance Regulatory Principles of Conduct, please click here.

“Psychology Works” Fact Sheet: Irritable Bowel Syndrome

What is Irritable Bowel Syndrome?

Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) include pain or discomfort in the lower abdomen (below the belly button area) and changes in bowel habit that involve frequent, urgent diarrhea or constipation. Bloating is another common symptom. IBS is a medical disorder primarily affecting the lower ‘gut’ (the small and large intestine) which is one part of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

IBS is a disorder of gut-brain interaction, meaning there are communication disruptions between the brain and the gut. IBS is understood to be a problem of the functioning of the gut. Research suggests that people with IBS experience abnormal gut motility (changes in the rate of contractions of the gut muscles), enhanced visceral sensitivity (an increased sensitivity to gas or sensations from routine activities that occur in the bowel), and changes in the gut microbiome (communities of microbes in the digestive tract, made up of bacteria, fungi, and viruses that, when balanced, help with digestion, nutrient absorption, and immune function).

It is not clearly understood what causes IBS. For some people it begins in childhood with a ‘sensitive stomach’ that develops into more intense symptoms as an adult; for others, the GI problems start suddenly during a period of stress or persist after an infection in the bowel. IBS is diagnosed based on the presence of the symptoms described above in combination with the absence of other ‘red flag’ symptoms (such as weight loss or bleeding).

IBS is very common. It is estimated to affect up to one in five Canadians. It often starts in young adulthood and occurs much more frequently in women than men. It is the second most common reason for missing work and is one of the most common reasons that people visit their doctor. In Canada, IBS has been estimated to cost over $350 million in direct and over $1 billion in indirect health care and productivity costs each year.

While the impact on society is quite significant, IBS can be very challenging for the individual. Pain, cramping, or urgent trips to the washroom may interfere with work and home activities. The bloating, gas, and urgency can be embarrassing, so people often suffer in silence.

Many people think certain foods must be the culprit but there is no evidence to support the idea that IBS is directly related to food allergies or food sensitivity. Once IBS develops, however, the bowel is over-reactive to or easily disrupted by a variety of potential triggers including diet, stress, emotional state, and even hormone fluctuations.

Stress does not cause IBS, but it does appear to play a particularly important role in triggering IBS symptoms, likely because of the close communication via nerves and chemical pathways between the brain and the gut. In fact, two-thirds of healthy individuals without IBS report GI symptoms of pain or bowel upset in response to stress and the numbers are even higher for people with IBS.

Research suggests that both ‘acute stressors’ such as deadlines, exams, job interviews, or conflict with others as well as ‘chronic stressors’ such as financial concerns, time pressures, or family issues can aggravate the gut.

How Can Psychology Help?

For those with milder IBS symptoms, use of over-the-counter medications and changes in lifestyle that ensure more regular eating and sleep routines, a healthier diet with increased fibre and water intake, as well as more regular moderate intensity exercise such as walking, swimming, or cycling, are usually sufficient to provide some relief.

However, for those with moderate to severe IBS symptoms, medical and psychological treatments are recommended. These treatments usually target specific symptoms, like pain, diarrhea, or constipation, or aim to decrease the triggers, such as stress, that aggravate the symptoms. Further, there is evidence that for some, implementing a special diet such as the low FODMAP diet for a focused period of time can improve aspects like abdominal pain and bloating, and provide direction for potential aggravating foods.

Conventional medical treatment has included fibre supplements, antispasmodics, gut motility agents, and medications that act on biochemicals such as serotonin in the GI tract and central nervous system. Medication decisions are usually guided by the predominant IBS symptoms. At this point, reviews of the effectiveness of the medication treatments have concluded that they are helpful for small subsets of people with IBS but have been disappointing overall in their impact. Newer medications in development are focusing on brain-gut pathways and the microbiome. For the most up-to-date information on medication treatments as they apply to your situation, you are encouraged to discuss the use of these medications with your family doctor.

Psychological treatments, which also target brain-gut connections, have been found to be effective in providing relief of IBS symptoms and reducing the distress and coping difficulties that often occur when dealing with a chronic illness. These psychological therapies focus on ways to decrease stress and cope differently so that the stress does not ‘go to the gut’.

What Psychological Treatments are Effective?

Psychological approaches have been carefully evaluated over the past number of years; Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and related therapies, as well as gut-directed hypnotherapy have specifically demonstrated well-established and lasting benefits. These brain gut behaviour therapies are provided by professionals trained in psychological interventions for health problems and can be delivered effectively in person or online. Medication, in contrast, tends to cease to have an effect when patients stop taking the medicine. Some research suggests that the amount of improvement in psychological treatment relates in part to the effort and time the individual contributes to working with the strategies.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) incorporates a number of steps aimed at changing behaviour to improve health and coping. It often involves providing information to ensure a better understanding of the illness (to help with fears and worries), teaching strategies to change thinking patterns that can contribute to strong emotional and physical reactions, teaching skills to deal with challenging or stressful situations that can trigger the gut, and goal setting to establish optimal health habits. CBT typically includes relaxation training.

Mindfulness and Acceptance-based therapies (ACT) are variations of CBT and emphasize learning ways to relate differently to symptoms, find meaning, and engage in valued activities despite the illness, broadening day to day functioning and overall wellness. These therapies may be offered on their own, or strategies from these therapies may be incorporated into CBT for IBS. Emerging evidence shows good effectiveness for those with severe and refractory IBS symptoms.

Gut-Directed Hypnotherapy uses mental imagery and deep relaxation to alter gut-brain communication, reduce unpleasant gut sensations, and reduce stress-related gut activity.

These psychological therapies are recommended by North American and European gastroenterology treatment guidelines for IBS. Cognitive behavioural therapy is the most commonly available type of psychological treatment for IBS in Canada and the United States, although medical hypnotherapy has become more accessible through scientifically evaluated online programs as well as digital apps.

Where Can I Go for More Information?

For more information about irritable bowel syndrome and steps you can take based on these psychological therapies:

- Scarlata, K., & Riehl, M. (2024). Mind your gut: The science based, whole-body guide to living well with IBS. Hachette Book Group.

- Hunt, M. G. (2022). Reclaim your life from IBS: A scientifically proven CBT plan for relief without restrictive diets (2nd ed.). Routledge.

For general information about IBS and similar gastrointestinal disorders please visit the International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders at http://www.iffgd.org or the Canadian Society of Gastrointestinal Research at https://badgut.org/.

You can consult with a registered psychologist to find out if psychological interventions might be of help to you. Provincial, territorial, and some municipal associations of psychology may make available a referral list of practicing psychologists that can be searched for appropriate services. For the names and coordinates of provincial and territorial associations of psychology, go to https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/PTassociations/.

This fact sheet has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by Dr. Lesley Graff, Professor and Head, and Dr. Maia Kredentser, Assistant Professor, Department of Clinical Health Psychology, Max Rady College of Medicine, University of Manitoba. Drs. Graff and Kredentser are registered clinical psychologists who work at Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba and whose research focuses on gastrointestinal disorders and behavioural medicine.

Revised: October 2025

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the PSYCHOLOGY WORKS Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

“Psychology Works” Fact Sheet: Autism Spectrum Disorder

What is Autism Spectrum Disorder?

Autism spectrum disorder (autism) is a neurological (brain-based) condition that influences the development of social and communication abilities, as well as other aspects of behaviour, in characteristic ways. The term “autism spectrum disorder” (ASD) reflects the current view that how autism affects learning and behaviour ranges from relatively mild to more significant in these areas of development. For example, the pattern of social and behavioural differences that defines autism co-exists with all levels of intellectual ability, although a substantial minority of autistic people have an intellectual disability.

Autistic people face challenges in understanding and relating to other people in typical reciprocal ways. For example, someone with autism may lack a natural grasp of interpersonal skills such as the ability to take another person’s point of view even when interested in social interactions and relationships. Non-autistic people may also find it hard to relate to the perspectives of autistic people. For some autistic people, language difficulties may make it harder to express their ideas. Even when language skills are strong, other differences in communication may affect social situations. An autistic person might have difficulty beginning a conversation or keeping one going in a fluent, two-sided manner. Autism may also be associated with reduced flexibility in thinking and behaviour. Their interests and activities may be intense or focused, which can be either a strength or a liability. For some autistic individuals, differences in sensory responsivity may include over- and/or under-reaction to lights, sounds, touch, tastes, odours, or pain.

Research shows that autism is a complex condition in which genetic, environmental, and societal factors interact; the specific causes are not yet known. The likelihood of developing autism is increased for children born to families who already have a diagnosed family member, and more boys/men than girls/women are affected by autism (although autism is also less often diagnosed accurately in girls and women). In its more severe form, autism is usually recognized by about age 2 years – often because the child is not yet speaking and shows limited interest in people. However, more subtle signs of autism may not be recognized until much later, often during the school years as differences from peers are noticed.

How is Autism Diagnosed?

Autism is diagnosed by an experienced clinician (usually a clinical child psychologist or a specialist physician) based on observed and reported patterns of behaviour. There is no medical test for autism. The diagnosis is made using in-depth information from parents and others about specific aspects of the individual’s development and behaviour, and the clinician’s systematic direct observations of behaviour. These observations cover both what the person does that may be characteristic of autism and doesn’t do that would be expected of a typically developing individual at that age or level of development. A comprehensive evaluation also considers the possibility of other conditions, such as intellectual disability, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or social anxiety disorder, that often lead to a suspicion of autism or co-occur with autism.

With earlier recognition in young children and a better understanding of both milder and more severe forms in people of all ages, the diagnosis of autism is becoming far more common. A recent Canadian estimate suggests that at least 1 in every 50 children is affected (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2022). The impact of autism varies, but autistic individuals and their families require health, education, and community services and supports. Many communities are trying to keep pace with the increasing need for autism-related services.

What Do We Do About ASD? Can Psychology Help?

Outcomes for many autistic people are far more positive than in past decades. Factors such as an individual’s levels of ability, presence of other health or mental health conditions, and importantly challenges accessing appropriate supports all contribute to highly variable long-term outcomes for autistic people. Some autistic individuals attain social, academic, and vocational success, as well as independent living, especially as communities become more accepting of neurodivergence.

Advances in psychological research have improved our understanding of the fundamental developmental differences as well as the strengths and challenges of autistic people. Psychologists have contributed to improved methods of recognizing, assessing, and intervening to support those with autism. Psychological assessment of children’s ability profiles – areas of relative strength and weakness – as well as evaluation of both autism characteristics and symptoms of co-occurring conditions can guide the development of appropriate education and therapies for autistic children. Treatments based on psychological principles are at the leading edge of autism intervention.

Early intervention can improve the quality of many young autistic children’s lives when strategies are used that capitalize on natural teaching opportunities in the home and community. Strategies based on the principles of learning can be used within the child’s daily routines with parents as partners in supporting their children’s development. Key areas for intervention usually include language/communication and social skills, daily living skills, self-regulation or coping skills, and family support. Peer-mediated interventions, in which autistic children and their nonautistic peers learn to play and communicate effectively, can promote more positive social opportunities. For older, able autistic individuals, cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) strategies can help manage common difficulties with anxiety or self-regulation.

Better access to evidence-based treatment for the mental health needs of autistic adults is needed in most communities. Psychologists and other mental health professionals are increasingly able to customize mental health care for autistic and other neurodivergent people. Community-based supports such as job coaching, recreational opportunities, and supported housing services are beneficial for many autistic people.

Where Can I Go for More Information?

- Autism Alliance of Canada: https://autismalliance.ca/

- National Autistic Society (UK): http://www.autism.org.uk

- Provincial associations of psychology: https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/PTassociations

- Psychology Foundation of Canada: http://www.psychologyfoundation.org

- American Psychological Association (APA): http://www.apa.org/helpcenter

You can consult with a registered psychologist to find out if psychological interventions might be of help to you. Provincial, territorial, and some municipal associations of psychology may make available a referral list of practicing psychologists that can be searched for appropriate services. For the names and coordinates of provincial and territorial associations of psychology, go to https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/PTassociations/.

This fact sheet has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by Isabel M. Smith, PhD. Dr. Smith is a registered Clinical Psychologist, Professor and former Joan and Jack Craig Chair in Autism Research, Departments of Pediatrics and Psychology & Neuroscience, Dalhousie University. Dr. Smith’s work at the Autism Research Centre at the IWK Health Centre in Halifax NS is focused on children and adolescents with ASD and their families.

Revised: October 2025

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the PSYCHOLOGY WORKS Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

“Psychology Works” Fact Sheet: Bipolar Disorder

What Is Bipolar Disorder?

We all experience changes in moods from time to time depending on events we go through in life. But when these mood swings become more dramatic and severe and impair a person’s ability to function as usual at work, school, or in relationships, it may indicate the presence of a serious mood disorder. Bipolar disorder, previously known as Manic-Depressive Illness, is a mental disorder that is characterized by severe mood swings cycling between periods of intense “highs” (mania or hypomania) and periods of intense “downs” (depression).

In mania, the individual experiences elevated perhaps extremely good mood, elation, or highly irritable mood that lasts for at least one week. This considerable increase in mood is accompanied by high levels of energy, combined with a noticeable decreased need for sleep. The individual usually has a boost in self-esteem, tends to talk more and faster, experiences racing thoughts, and is easily distracted. Mania is also characterized by an increase in goal-oriented activities and often leads to excessive involvement in pleasurable activities that have a high potential for painful consequences (e.g., excessive and irrational spending, sexual indiscretions, reckless driving). In more severe forms, mania can be accompanied by psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations or delusions and almost always requires hospitalisation. Hypomania, a milder form of mania, causes less impairment but can often go unnoticed for several years before receiving appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

In the depressive phase of bipolar disorder, symptoms of clinical depression (or Major Depressive Episode) need to be present for at least two weeks and are like symptoms of unipolar depression (see the Canadian Psychological Association’s fact sheet on Depression). These symptoms include depressed mood or sadness, loss of interest in most activities, decreased activities or social withdrawal, changes in appetite, increased or disturbed sleep, fatigue or low energy, decreased sexual desire, difficulties in concentration or making decisions, feelings of worthlessness and suicidal thoughts or plans. In more severe forms, clinical depression can be life threatening and require hospitalisation as suicide is a significant threat in bipolar disorder.

In Canada, around 2% of individuals will experience bipolar disorder at some point in their lifetime. Bipolar disorder usually starts in late adolescence or early adulthood, but it can also begin as early as childhood. It affects both men and women equally. Bipolar disorder is a highly recurrent disorder, meaning that most individuals with bipolar disorder will experience several episodes during their lifetime. Significant mood symptoms between episodes, problems with being able to get back to work, as well as relationship difficulties and break-ups are common in bipolar disorder.

Although we don’t know exactly what causes bipolar disorder, we do know that genes and chemicals in the brain play a strong role in making people vulnerable to developing the disorder. Stress alone does not cause bipolar disorder, but episodes of mania or depression are often triggered by stressful life events. Risk factors for relapse in bipolar disorder include abusing alcohol or drugs, not taking psychiatric medication as prescribed, and changes in routine leading to a lack of sleep or irregular sleeping habits.

What Psychological Approaches Are Used to Manage Bipolar Disorder?

Pharmacotherapy, or drug therapy, is essential for the treatment of bipolar disorder. It usually involves the use of one or more mood stabilizers, such as Lithium, combined with other medications. Though, there is now strong evidence that psychological interventions can be added to drug therapy to help people better manage their illness and reduce repeated experiences of mood episodes.