Psychology is rooted in science that seeks to understand our thoughts, feelings and actions. It is also a broad field – some psychology professionals develop and test theories through basic research; while others work to help individuals, organizations, and communities better function; still others are both researchers and practitioners.

Profiles

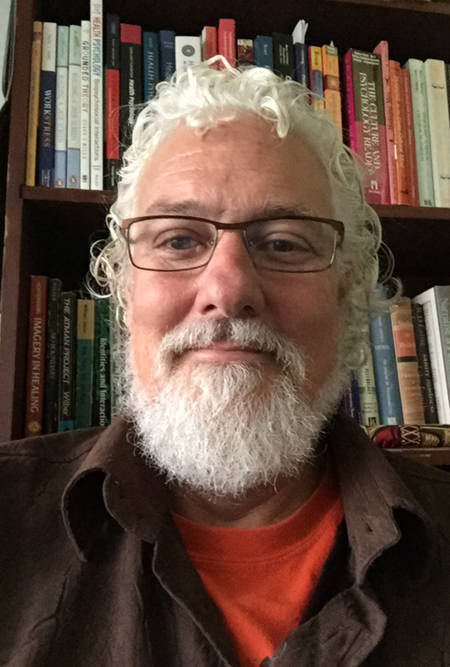

On this week’s Mind Full podcast we’re focused on one way psychology interacts with the healthcare system, specifically in the field of HIV and AIDS. Our guest, Dr. Sean Rourke, just won a major award for his life’s work, the inaugural Eric Jackman award from the Royal Society of Canada. From the days when an HIV diagnosis was seen as a death sentence to today, when early detection can result in a long and full life, he has been helping Canadians in a myriad of ways.

Just about every little kid has accidents from time to time. But more than one poop accident in a month (encopresis) or more than two pee accidents per week (enuresis) might be cause for concern. Dr. Jen Theule helps explain what signs to look for, how best to potty-train kids, and how psychologists help resolve problems that might occur as children get a little bit older.

How do we gather information to store it in our memories? How do we retrieve that information when we need it? And can you actually forget how to ride a bike? Dr. Elena Antoniadis, psychology professor at Red Deer Polytechnic and an adjunct professor at the University of Calgary, joins us for a look at how we form memories, how we can enhance our recollection abilities, and more.

Zaineb Bouhlal, the CPA’s Membership Database and Services Administrator, says she has forgotten how to ride a bike. Is such a thing possible? After all, it’s the most-clichéd thing we’re all supposed to remember as long as we live. “Like riding a bike” is the phrase used to describe most everything we store in our procedural memory. Biking, swimming, typing, driving a car, any skill that involves sensory-motor coordination that we’ve practiced and acquired is one we can re-gain if we’re put back into that same setting.

Dr. Elena Antoniadis is a psychology professor at Red Deer Polytechnic and an adjunct professor at the University of Calgary. She says,

“Once you’ve learned to drive a car it would be very difficult to forget how to carry out all the operations that go into driving a car. But it’s not a memory that our conscious or declarative systems have access to. So, for example, we can’t tell a younger sibling how to ride a bike – it’s not something we can write a manual for. It’s something that the body registers, and then the implicit memory system builds the memory of that skill.”

There are memories that are encoded explicitly – like facts, knowledge, the things you learn in school. You are making a conscious decision to remember those things, and what makes a memory “explicit” is that we can consciously access it and describe its contents, rather than simply showing it through behaviour. Then there are memories that are encoded implicitly – this is how we build habits, conditioned reflexes, and learned responses. The brain registers patterns without us being aware of them. The basal ganglia in the brain helps us build the skills, the habits, and the automatic responses that come from the implicit encoding of memories. Language is often one of those areas that we learn implicitly from a young age.

Before I worked at the CPA, I worked at The Dementia Society of Ottawa & Renfrew County (DSORC). DSORC runs programs for people living with dementia, programs which often make use of deeply encoded memories to recall songs from childhood, or to move and exercise in familiar ways. When I was there we had an Arabic-language program, for people who had grown up in the Middle East but now lived in the Ottawa area. One older man came to that program with his family. They had come to Canada from Saudi Arabia a decade prior, and now their father was living with dementia. Unfortunately, the program wasn’t working very well for him because, although he had spoken Arabic with his family for his entire life, he no longer spoke the language. Instead, he was speaking a language they had never heard before. After a while, the Dementia Care Coaches determined that he was speaking Farsi. He had grown up in Iran, but had never told anyone in his family about his childhood in another country. Now that he was losing his short-term memory, and his longer-term memory was starting to fragment, he was left only with those memories that had been deeply and implicitly encoded in him some 75 years ago.

By contrast, memories that have been explicitly encoded behave differently. We use different methods to retrieve them, and our methods change over time as we experience more of the world from a personal perspective. Says Dr. Antoniadis,

“Children are more emotionally attuned to those around them, their environment, and their primary caregivers. They rely more on the emotional parts of the experience to build their memories. As we age we can rely more on our own lived experiences, the episodes that take place in our lives. I witness this in my own classes. I see mature students who are returning to school, and they can connect something factual with something they’ve experienced in the workplace or in a familial environment. Because they have a broader repertoire of meaningful experiences they can connect with the information they’re receiving.”

That increase in experiences can be a little bit of a double-edged sword when it comes to memory. Think of major events that happened in your life, and the way you remember them now. For me, a good example is 9/11. I know I was in radio school, and that I was with Vicky McKenzie. But when I discuss that moment with Vicky today, we have very different recollections of how we responded, who was around, and what we did next. Either one of us is right and the other wrong or, more likely, we’re both a little bit wrong.

A major event like that one feels like it happens in an instant, and that we have a snapshot in our minds that will be accurate forever. But it doesn’t really happen in an instant. After the event, there is news coverage of it. Your family is going to be talking about it, your co-workers or fellow students or schoolyard friends will also be talking about it. Now, within a few months of the event, you have added untold amounts of information to that first memory, which can distort your recollection of the specific facts.

I am almost certain that we watched, in real time, the second plane hit the World Trade Centre. Vicky says we started watching only after that happened. I remember going, later that afternoon, to donate blood with Jamie Johnston. Partly because we didn’t really know what else to do, and partly to put on our journalist hats to talk to people who were also doing the only thing they could think of in that moment. Jamie tells me we actually did that several days later. Dr. Antoniadis says this is quite common.

“Many times we have factual information about an occurrence. That information comes in separate from the memory itself, but becomes integrated into the memory. This is the reason why sometimes police officers who arrive at an accident or something like that will separate witnesses to make sure their stories don’t impact the other person’s recollection. Hearing another witness describe what they saw can become integrated into our own memory of the event, even one that happened moments earlier.”

In 1994, Chuck Knoblauch of the Minnesota Twins finished the major league baseball season with 45 doubles. That season was shortened by a strike that resulted in no World Series being played, much to the chagrin of Expos fans who thought they had a great chance at their first title, and Blue Jays fans who were denied a chance at a three-peat. Had the season lasted a full 162 games, Knoblauch was on pace to hit 65 doubles and threaten the all-time record of 67 set by Earl Webb in 1931 with the Red Sox.

This is a fact I know. It’s one that has stuck in my brain since my youth, and while there’s no good reason for me to remember, I have never forgotten what might have been in 1994. I find it somewhat interesting. My wife finds it somewhat irritating. “You can remember how many doubles Chuck Knoblauch hit in 1994, but can’t remember that you were supposed to take the garbage out?” she’ll say. And I will respond with “I dunno – that’s just how my brain works, I guess”.

It turns out though, that this is how all of our brains work! Our capacity for short-term memory is finite, but our long-term memory retention is – as far as we know – limitless. Dr. Antoniadis explains more.

“Short-term memory has limited space, but long-term memory is limitless in its storage capacity. We have variety in the mental operations we perform – encoding, storage, and retrieval. But we also have variety in the types of information that we create. Long-term memory is, according to the scientific literature, limitless. We can continuously keep learning and acquiring new information.”

Dr. Antoniadis says that because our short-term memory has a finite capacity, there can be a bottleneck where we are subconsciously deciding whether to commit information to more long-term retention, and deciding what ideas we might discard. I likely won’t need to remember, ten years from now, that I took out the garbage today or shoveled the driveway. It won’t come up in pub trivia. But Shohei Ohtani’s 3-homer 10-strikeout playoff game…that might come up! It’s going in the vault.

So, I’ll remember that for pub trivia purposes, and it may or may not come in handy a decade from now. But what of the people who excel at that kind of memory retrieval? The people like Ken Jennings, Mattea Roach, or Amy Schneider who can get on Jeopardy! and just crush it?

“Retrieval depends heavily on cues and context. Individuals who are practicing retrieval and recollection of accurate information may be using retrieval cues that will help them enhance that. Can they use something about where they were at the time they learned it? What they were doing when it happened? They’re focused on matching the cues that were present when that information was presented. This happens in school too – if you’re writing an exam in the classroom where you learned the information, you’re more likely to be able to retrieve that information than you would be if you wrote it in a different classroom.”

So…does that mean that the old adage is true? The one that says if you study under the influence of weed or alcohol you should write the exam in the same state so you can maintain the same frame of mind and to increase the likelihood that certain cues will assist you in retrieving the information you need? Dr. Antoniadis says yes.

“The concept is supported research findings. It’s called ‘state-dependent memory’. When we’re in a certain state – an emotional state for instance – we’re more likely to retrieve memories from that state. When we’re happy, we retrieve joyous memories. When we’re sad, we’re more likely to recollect sad memories. When our physiological or emotional state matches experiences we’ve had with a similar state, we’re more likely to retrieve the memories from that time.”

We hear a lot about scent and memory in popular culture. Perhaps more than any of our other senses, smell triggers memory cues in subtle ways that make it easier for us to recall old events or retrieve information buried deeply in our minds. Dr. Antoniadis says this is because our olfactory sense (smell) is very much connected with the parts of the brain that houses the instinctual parts of our memories.

“Instead of it being something we are consciously aware of, or something we can explain or articulate, it’s a non-declarative memory. That means it’s something we feel, something we can enact or show through our behaviour, without being able to explain it. We might have an emotional reaction to a frightening cue without being able to explain why we responded that way. Other times, emotional reactions can be the impetus to conjure up the conscious memory if it’s there. It can be a gateway to a conscious recollection of a specific memory.”

A lot of memory exists in a place beyond our specific awareness. When we say we can’t remember something, that doesn’t necessarily mean we haven’t stored the memory, but that we’re having trouble retrieving it. Like thinking we have forgotten how to ride a bike, when in fact we might well remember exactly how to do so when we’re put in a situation that is reminiscent of the time when we did ride a bicycle all the time.

At the CPA, we are going to put this to the test. It will be an anecdotal study, and the data will be applicable only to Zaineb. Once the snow has melted, in late May or early June, and Stewart starts riding his very expensive bike in to work again, we are going to perform an experiment in our parking lot to see if Zaineb can, in fact, summon the bike-riding knowledge she once had when put in that situation. It will be one more experience that we can all add to our repertoire of experiences that allow us to draw on our memories.

Stewart’s bike is very nice, and he takes tremendous care of it. We will wait until the day we conduct the experiment to tell him that his bicycle has been volunteered. So don’t tell him before then.

The recipient of a donation from the CPA’s Orange T-shirt sales at our 2025 convention is First Light, an Indigenous-led organization in St. John’s, Newfoundland. First Light has seven locations in St. John’s that assist urban Indigenous and non-Indigenous people who are experiencing homelessness, mental health issues, and who require supports in the St. John’s area.

Just outside the convention centre in St. John’s, Newfoundland, is a bus stop where many locals congregate during the day. While the 2025 CPA convention was being held in St. John’s, there were two Indigenous men who spent the whole day there. They weren’t waiting for a bus but, rather, seemed to be waiting for opportunities to converse with the large number of psychologists who had suddenly come from away. They were quite happy to tell us all about their hometowns, about the most picturesque locations in the province, and to act as de-facto tour guides suggesting the places outside the city we all had to visit.

Over the course of three days, we learned from those two men about some of the Indigenous history of St. John’s, but mostly about the history of the rural parts of the province. They told me about the nine-day hunger strike in 1983 by Mi’kmaq activists – a hunger strike that prompted the Newfoundland government to finally release $800,000 in federal funds that had been supposed to go directly to the community of Miawpukek. The funding had been held back for more than a year because the provincial government wanted to take a significant portion of the money for themselves for “administrative purposes”.

I learned even more about this hunger strike from Stacey Howse, the Executive Director of First Light, when I spoke with her this month. She pointed me to the CBC Gem documentary The Forgotten Warriors, which details the 1983 strike in Conne River and exemplifies the struggles faced by Indigenous people in Newfoundland. Their history is not taught in the school curriculum there. When Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949, the Indigenous population was not only ignored, but specifically excluded, which meant that services and supports that could have helped were not made available. Since then, the province – and organizations like First Light – have been playing catch-up.

Says Stacey, “so many people don’t understand the history of Indigenous people here in Newfoundland and Labrador. It’s not in the school system, and as a matter of fact there was inaccurate information in some of the existing social studies books about the Beothuk and the Mi’kmaw people which differed tremendously from our oral history. We’ve been working very hard to teach the history.”

First Light has seven locations in St. John’s that assist urban Indigenous and non-Indigenous people who are experiencing homelessness, mental health issues, and who require supports in the St. John’s area. The vast majority of Indigenous people in St. John’s who need the supports First Light provides come from the surrounding communities and have deep ties to the land in the rural areas of Newfoundland and Labrador.

First Light is an Indigenous-led “wraparound” agency, meaning it provides many services which all work in concert with one another and which cover, as best they can, all the varied needs a person in St. John’s experiencing homelessness might require. Stacey talks passionately about the ‘Housing First’ model, which suggests that the first thing people experiencing homelessness need is housing. It’s all well and good to provide a host of services – employment, education, mental health, addiction services – but having stable housing is the most important part. With stable housing, accessing those services becomes much easier. Without it, the effectiveness of wraparound services becomes greatly diminished.

During the 2025 CPA convention, there were several presentations that touched on homelessness (Correlates of PTSD Symptom Severity in Homeless-Shelter Support Staff, Experiences of Women and Gender Diverse Individuals At-Risk for Homelessness) and several others that touched on Indigenous issues (Exploring Priorities for, Concerns about, and Definitions of Nature Connection in Curve Lake First Nation, Methods of Weaving Reconciliation Promotion in Psychology Curriculum). When delegates left the convention centre, we could see first-hand the need in downtown St. John’s for the services provided by First Light.

At every convention, the CPA sells orange T-shirts designed by Betty Albert, and chooses a local charity for a donation derived from the sale of those T-shirts. In 2025, we chose First Light. We chose them because they offer the kinds of services that are carefully and pointedly designed to achieve the best results for the urban Indigenous population, and for people experiencing homelessness. We also chose them because they are dedicated to telling the stories, and sharing the history, that led Indigenous people to St. John’s in the first place.

It's the kind of story you’re unlikely to hear without the work of Indigenous knowledge-keepers in Newfoundland and Labrador. That is, unless you have a few days to hang out at the St. John’s convention centre bus stop.

Liisa Galea

Dr. Liisa Galea is a scientific lead for the CAMH (the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health) program womenmind™. It’s a community of philanthropists, thought leaders and scientists dedicated to tackling gender disparities in science, and to put the unique needs and experiences of women at the forefront of mental health research.

Womenmind™ Liisa Galea

“You know how to *take* the reservation, you just don't know how to *hold* the reservation. And that's really the most important part of the reservation: the *holding*.”

- Seinfeld, ‘The Alternate Side’, 1991

The National Institute of Health (NIH) in the US introduced a policy* in 1993 where applications for research that plans to involve human subjects for clinical trials must address the inclusion of women, minorities, and children in the proposed research. As a result, the scientists applying for research grants did exactly that. They included women, minorities, and children in their studies. But to what end?

It’s easy to include women, minorities, gender diverse people, but if you don’t look to see if it’s affecting outcomes for those individuals differently, then you’re doing only half of the work – and missing the part that makes inclusion important. But precious little research, since the introduction of that policy, has made that distinction.

*It should be noted that it is quite difficult, at the moment, to ascertain exactly when the NIH instituted that policy, or what the outcomes have been, since the new American presidential administration has scrubbed their websites and resources of any language involving “minorities”, “disparity”, “bias”, and even “women”.

Dr. Liisa Galea leads the Women’s Health Research Cluster at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) in Toronto. She is the principal editor of Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, the Past President of the Organization for the Study of Sex Differences and co-Vice-President of the Canadian Organization for Gender and Sex Research. She is also the scientific lead for the CAMH initiative womenmind™ and a Seinfeld fan.

“I grew up in a time when I had to wear a skirt in school because I was a girl. I’m so grateful to my parents for saying I was smart and could do anything I wanted to do…except perhaps become Pope! I was told I was different because I was a girl, but it didn’t upset me – it just made me curious as to why people thought that. When I started university, I got really interested in the area of female brains vs male brains and I wanted to know all about the differences and what that might mean for our health.”

womenmind™ is a community of philanthropists, thought leaders and scientists dedicated to tackling gender disparities in science, and to put the unique needs and experiences of women at the forefront of mental health research. Dr. Galea and Dr. Daisy Singla, a clinical psychologist who specializes in perinatal mental health, are womenmind™ scientists who do a lot of this important work.

The gender disparities in healthcare are real, and they are significant – particularly in the area of mental health. Diagnoses of mental health issues can take up to two years longer for women compared to men. There is a sense in the public sphere that men don’t talk about their feelings as much as women do, and are less likely to seek help with psychological issues. Despite this, just looking at mental health disorders, there is still a delay in diagnosis of more than two years for women. That delay can interfere with treatment plans – if you’re being misdiagnosed or dismissed with your symptoms you’re not getting the treatment you need, and we all know that earlier interventions lead to better outcomes.

A study done by the World Economic Forum showed that globally, women spend 25% more of their lives in poor health than men do. Dr. Galea thinks this is partly due to health science being historically dominated by men studying males.

“In terms of mental health specifically, there are many reasons for the delays in diagnosis, but one of the major reasons I think is because most of our medical knowledge – including the symptoms on checklists for diagnoses – are based on the experiences of men. So much so, that we often call symptoms for mental health disorders in females ‘atypical’. We use ‘atypical’ a lot in the context of neurodiversity – autism, ADHD, and so on. And there are more males diagnosed with those conditions. We see more females than males diagnosed with depression, but we also see that ‘atypical’ label applied to depression in women. If there are twice as many women diagnosed with depression as men, how are their symptoms ‘atypical’? I think it’s because our scales were developed a long time ago, thinking about findings in males and the experiences of men.”

As a result, healthcare providers don’t acquire enough knowledge about sex and gender disparities in disease presentation and symptoms. This has real consequences for women in the healthcare system, but also for funding bodies. As a researcher that’s been in this field for 28 years, Dr. Galea gets a lot of comments from editors and funding agencies that *this [female-centric subject]* isn’t a really important thing to study because it’s “only in a subset of the population”.

Dr. Galea and her team did a review, looking only at male/female studies in neuroscience and psychiatry. 68% of studies were using both male and female participants, but only 5% of those studies looked to see whether sex made a difference. As Dr. Galea says, “you can have 2 females and 8 males in your control group, but the reverse in the treatment group, and you can’t do the analysis properly because you don’t really have the sample size to see if it made a difference.”

27% of the studies were focused solely on males, and 3% solely on females. Dr. Galea’s team then looked at Canadian grants, which resulted in similar percentages. In 2023, mental health specifically for women made up less than 1% of the funding of the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR), the major federal agency responsible for funding health and medical research in Canada.

Funding for research is, sadly, a hot-button issue at the moment as the new American government tries to shut down funding at the NIH for everything they deem to be “woke”. This has impacted many of Dr. Galea’s colleagues and the work they do, especially since the cuts seem to have been attempted in the most damaging and misguided way possible. The new administration looked for the key words they didn’t like, and cut funding for everything that contained words like “bias” or “diversity” or “environmental”. They also targeted words like “trans”, “non-binary”, “female”, and “woman”.

This could result in the ending of studies into things like the gut microbiome, where one of the measures is alpha-diversity and beta-diversity – referring to the variety of bacteria that live in one’s gut. Electricity studies using vacuum tubes which require a current called “bias”. And studies involving women’s health. Dr. Galea says this is even more dangerous than it seems, because stopping the study of women’s health affects men as well. She gives an example,

“Lazaroids were a drug that was discovered for stroke recovery. It worked miracles for people who had suffered strokes. It was discovered pre-clinically first, where it worked on mice and rats, and then it went to double-blind randomized control clinical trials, our gold standard. It turns out most of the pre-clinical work was done in males. The early clinical trial was done all in men as well, since men are more likely to suffer a stroke earlier in life (but this switches to more women later on in life). It failed phase 3 clinical trials, which included women, and the drug is not on the market. It put the drug company out of business. But when people did secondary analyses, it turns out lazaroids work wonders in men – but not in women. In fact, in women it might have made things worse. But that’s a drug that’s now not on the market that might do wonders for men’s health! Isn’t it in our collective interest to find out what drugs work better in different populations?”

This upheaval could have devastating consequences for the future of women’s health, an area that has critical problems already. Consider menopause. This is something that will happen to 50% of the population. And yet, 0.5 % of all studies in neuroscience, and in the field of brain health in general, are on menopause. Physicians get about 1-3 hours of training on menopause and its effects on health.

When women go through menopause and have significant problems, they get sent to specialists – gynecologists. But – only 30% of American gynecological programs had anything about menopause in them. So well above half the time women get sent to see specialists for this, they’re going to see someone who hasn’t been trained in it, and may have learned very little about it. Says Dr. Galea,

“We have to become our own specialists, but we need informed research to know what we can do to offset our symptoms. Laura Gravelsin (one of my postdocs) and I just had a paper accepted called ‘One Size Does Not Fit All: Type of Menopause and Hormone Therapy Differentially Influence Brain Health’, because there are many hormone therapies and many menopauses, and we have to determine which one works for us individually.”

Not all scientists who study women’s issues are women, and not all women specialize in those issues. But having more girls going into scientific disciplines, and being supported along the way, can’t hurt. This is another of womenmind™’s goals. Dr. Galea points to the fact that there are more female psychologists, and physicians, than there are male. And yet, at the dean level, or director or supervisor level, the proportion of women steadily decreases the higher in rank you go, compared to men. She says,

“Girls are very interested in all scientific fields at a very early age, but as time goes on and we get further and further in our career, the disparity starts to grow. At the university level, you see more women and girls in the sciences, but the gap gets a little wider the further up you go, at the graduate level and then at the assistant professor level.”

With this in mind, womenmind™ has a robust mentorship program for all female and gender-diverse scientists that has seen remarkable results. About 60% of the female and gender-diverse scientists at CAMH have gone through the mentorship program, and there is a staggering 100% approval rate – every single person coming out of the mentorship program has said they would recommend it and they want it to continue.

And continue they will, with the passion and determination of the new scientists and the veterans like Dr. Galea. In addition to womenmind™, she runs her own lab investigating how hormones (mostly estrogens) influence the brain. They focus on stress-related psychiatric disorders like depression, and also Alzheimer's. Dr. Galea also runs the Women’s Health Research Cluster which in the realm of knowledge translation, and seems like a lot of fun! They just had an event in Toronto called ‘Galentine’s Day: Love your Brain’ which was about girls and women and anyone who identified as such loving their brains through hormonal changes like puberty and menopause.

The experiences of women and girls going through hormonal changes are varied and diverse. The path through adolescence, or menopause, is rarely a straight line. Nothing in life is a straight line! Even Dr. Galea’s journey to doing the work she does today (and Parks and Rec fandom) took numerous twists and turns. She says,

“I started in engineering first, and took Psychology 101 with Susan Lederman. She works in perception. She said ‘I’m the first Canadian, the first woman, and the first psychologist to be asked on a NASA panel’. She was there because astronauts were complaining they couldn’t feel anything through their gloves when they were out on a spacewalk. I was hooked. I thought, ‘that’s so interesting, I want to learn that’. It’s not at all what I ended up doing, but I took a lot more psychology as a result. I ended up studying women’s brains, and I’m always going to do it!”

Someone’s got to do it. And someone else entirely has to support them by making it a priority to ensure they continue to get to do it. With initiatives like womenmind™, the Women’s Health Research Cluster, and the research being done by Dr. Galea and her colleagues, the future of gender-inclusive health science looks promising. But if we want to make the most of that promise, the scientific community and policymakers must make it a priority to ensure this research continues.

Madeline Springle is a second-year Ph.D. student at the University of Calgary, who is winning awards for her ability to mobilize knowledge. Specifically, she is taking the research she has done into one-way video interviews, and using it to help people who might use this knowledge to better prepare for their own job search.

As we close out Psychology Month, we wanted to highlight knowledge translation (explaining the science for a more general audience) and knowledge mobilization (putting new findings into practice such that they help those they were designed to help) because without those, science exists in a vacuum!

Cette semaine, dans le cadre du Mois de la psychologie dont le thème, cette année, est « Les femmes et la science », nous présentons Sophie Bergeron, Ph. D., qui détient une Chaire de recherche du Canada sur les relations intimes et le bien-être sexuel au Département de psychologie de l’Université de Montréal, où elle dirige également le Centre de recherche interdisciplinaire sur les problèmes conjugaux et les agressions sexuelles (CRIPCAS), l’Équipe SCOUP Sexualité et Couple, et le Laboratoire d’étude de la santé sexuelle. Ses travaux portent sur les déterminants psychosociaux de la santé sexuelle des individus et des couples ainsi que sur le traitement des dysfonctions sexuelles.

There has always been a stereotype that women are “more emotional” than men, and even that they are “too emotional” for leadership roles. Dr. Winny Shen joins Mind Full to discuss the results of her study which suggest that not only is that stereotype untrue, the exact opposite might actually be the case.

Jessica Strong

We all plan to get older. So why do so few of us gravitate toward working with older adults? Dr. Jessica Strong is a Geropsychologist in the department of psychology at the University of PEI. She tells us about cognitive reserve, fights against ageism, and discusses how a passion for music led her toward her current career path.

“You see the hood's been good to me, ever since I was a lowercase g. But now I’m a Big G.”

- Montell Jordan

In his monster 1995 hit ‘This Is How We Do It’, Montell Jordan makes the distinction between a “lowercase g” and a “Big G”. In his case, he’s making reference to being a young child, understanding and evincing the gangsta part before he grew to adulthood and achieved proper, professional gangsta status by releasing a staggeringly popular debut single.

Like Montell Jordan, it was music that led Dr. Jessica Strong to her eventual career path, one where she too makes a distinction between lowercase gs and Big Gs. ‘Big Gs’ are the expert specialties, Geriatrics, Gerontology, Geropsychologists like Dr. Strong. ‘Lowercase g’ refers to the little competencies everyone needs to have. Social workers, family doctors, personal support workers at retirement residences, caregivers, or retail workers. Anyone who deals with an older population in their day-to-day lives. Says Dr. Strong,

“I have a lot of students who aren’t necessarily interested in Geropsychology (big G), but we work on developing this ‘lowercase g’ workforce, which is not working with older adults exclusively. They may be a generalist psychologist, but one who has the competency to work with older adults. They understand the cohort issues and generational differences, and know how to modify an intervention or screen for mild cognitive impairment.

I tell all our clinical students ‘you want to work in paediatrics, great! How many grandparents are raising children these days? For your paediatric client, if you’re noticing something off with their grandparent, you’re going to want to figure out whether this is anxiety and stress because they’re raising a nine-year-old, or could this be a mild cognitive impairment? And how am I going to figure that out in a way that serves the interests of my paediatric patient?’”

Dr. Strong is an assistant professor in the department of psychology at UPEI, and a registered clinical psychologist who specializes in Geropsychology. Geropsychology is a subsection of gerontology – the broad study of aging, lifespan, development and identity in late life. It’s a discipline that focuses on relationships, mental health, cognition and more generally the psychology of aging.

It was music that led her toward this career path, as she started playing piano at the age of 9 and soon picked up more instruments, playing alto sax in the high school marching band. It was in high school that she started thinking about music therapy as a career. But music therapy is a pretty specialized occupation, and Jessica is someone who likes to keep as many options open as possible.

In her final year of high school, right around the time we were all learning that “southcentral does it like nobody does”, she shadowed the music therapy program at her local university. She quickly realized that there was a way to get into this while keeping more doors open, and she ended up doing two simultaneous undergraduate degrees – one in music performance, and one in psychology. The idea was that from there she could get a Master’s in music therapy if she chose that path.

But psychology research really spoke to Jessica, who started to become far more interested in the mechanisms of why music makes a difference for people, rather than just using it as a tool. She had done a little bit of work with older adults at an occupational therapy lab at Washington University in St. Louis. Then she moved to Germany, where she worked at a mental health institute for older adults, the Central Institute for Mental Health in Mannheim. She had become a lowercase g.

Soon, she realized that what she really wanted to do was work with older adults. She had never heard the term “Geropsychology” before, but she lucked into a program at the University of Louisville in Kentucky, and was accepted into their Clinical Psychology program, working under the mentorship and supervision of two Geropsychologists. She earned her Ph.D., became a Big G, and says she has never looked back.

“One of the most rewarding things about working with older adults is that they are some of the more complex human beings in the world. They’re such a heterogeneous population because they have all of the demographic differences that any of the rest of us have – gender and race and so on – but they also have all their lived experiences and the changes that have come with those. Physiological aging, emotional aging, cognitive aging. It’s really intellectually stimulating and exciting for me because they’re so much more complex than any of the other groups I’ve worked with who haven’t done as many things.”

Soon, Dr. Strong was working in Boston at a rehab facility in the Veteran’s Health Administration. She studied how integrating music into a mental health group could destigmatize talking about mental health for older male veterans. They got some great feedback, the veterans felt like this group was different from others they’d been in before, and that the use of music made it easier for them to talk about things that both as men and as veterans they’d been conditioned to avoid. Music gave them a way to feel it without necessarily having to find the words.

One of the sessions Dr. Strong did with this group used “a bit of a music therapy technique”. They would start the group session by reading the lyrics to a song aloud, like a poem. They’d talk about the imagery, and what they thought the artist was trying to convey. Then they would listen to the song to see if it felt different than just reading through it. Did the addition of music take away from the message, or did it add something? The veterans in the group, men whose gender and military service compounded a reticence to speak vulnerably, went to deep places dissecting the music.

Dr. Strong says ‘What A Wonderful World’ was a group favourite. Given the age of the participants (some Vietnam veterans, others Korean War veterans, and some survivors of World War II) it makes sense that a song from the 60s resonated as much as it did. Music is often associated with memory and nostalgia, most particularly the music we heard around major life events in our adolescence and in early adulthood. Like a wedding song, a graduation song, or one you heard while you were heading off to war.

When similar sessions are held forty years from now, there’s a good chance a psychologist like Dr. Strong will be integrating much different music into this kind of group therapy. They will discuss what Mr. Jordan is trying to convey when he suggests we “flip the track, bring the old school back”. Dementia support groups that connect people through sing-a-long music will sound like one of those Pitch Perfect mashups. “I reach for my 40 and I turn it up / designated driver take the keys to my truck”.

Music not only triggers memories, it shapes our brains as we age. Dr. Strong is specifically interested in the brains of musicians, and the effect a lifetime of playing music has on the aging process. She talks about something called Cognitive Reserve. This is the idea that everything we do in our lives builds up a reserve in our brains. Dr. Strong describes it like a battery you can charge. Having a formal education, speaking a second or third language, having strong social connections, these are factors that charge our battery and make us more resilient against cognitive impairment later in life.

“If someone has a really high cognitive reserve, a scan of their brain might look awful, with disease, or vascular damage. But they might still function okay because they’ve built up this reserve over time that allows their brain to circumnavigate those damaged pathways. Someone with a lower cognitive reserve might have a brain that looks relatively okay on a brain scan, but they might be showing signs of mild or moderate dementia in their functioning.”

According to Dr. Strong’s studies, and similar studies by her peers, musicians tend to do better in some things as they get older, like in executive functioning and language, but not in all areas. One of the areas where they don’t tend to do better than non-musicians is in memory. Some have suggested that the tests for memory are flawed, and this may be the reason we don’t see a correlation between that and musicianship. When Dr. Strong takes a sabbatical next year, this is one of the things she’s hoping to learn from a longitudinal data set she has collected. But she has learned a lot already from her research up to this point.

“I’ve compared people who retired from playing versus those who continued to play. That was an interesting study, where I found that people who stopped playing lost the benefit they had in some of the more fluid abilities like executive functioning, but maintained the benefits they got in crystallized abilities, things like language. People who continued to play continue to have both benefits.”

There are many challenges to working with older populations, in particular defining what those populations are. The general (Dr. Strong says arbitrary) line at which Geropsychologists and Gerontologists start looking at people as “older” is the age of 65. But they’re also working with people who are much older than that.

“What gets complicated about using 65 as the arbitrary cutoff is that you’re still including people who are 80, 90, even over 100. There are people over 100 participating in research, and you get into this really interesting scientific conundrum of having people who span 30 or 40 years in a scientific sample. Which is absurd – never would we put 10-year-olds and 50-year-olds in the same sample, and this is somewhat of the same construct.

So this is a problem when we work with older adults, and a lot of Gerontology and Geropsychology splits those groups up into the ‘young old’ (65-74), ‘old old’ (75-84) and ‘oldest old’ (85 and up), trying to get a little more nuanced perspective. These people grew up in completely different ways and in completely different cohorts. And a 65-year-old shouldn’t and wouldn’t be expected to be in the same life place as a 95-year-old.

It's a lot easier to get access to research participants who are in that young-old group, so they tend to be overrepresented in research. It’s a lot harder to get a representative sample for the older groups.“

Another challenge is ageism. This is something that matters a great deal to Dr. Strong, and she gets impassioned when she talks about the ways we neglect our older population. Age is a diversity factor that is often overlooked, and Geropsychologists are constantly reminding their organizations, and anyone who will listen, that age must be thought of and included as a diversity factor. Not valuing older adults, the negative attitudes we have about getting old, looking old, and acting old, create real-world harms. Dr. Strong says these are some of the reasons we have a lack of action in overhauling Canada’s long-term care system.

“We know what works in long-term care, it’s just a matter of putting it in place. It wasn’t necessarily intended to be this medical-type institutional facility. People don’t want move there because it signals the beginning of the end, and they think that because of how those facilities work. They’re understaffed, underprioritized. Some of the most amazing models of long-term and dementia care are in Scandinavia. There are enclosed ‘dementia villages’ where people live in their apartments, but they can go shopping and go wander in the park. The person cutting the grass is a trained dementia nurse, as is the barista at the coffee shop. But many of us don’t see older adults, and particularly older adults with dementia, as important enough to care.”

We’re all going to get older. As Dr. Strong tells her students, “if you’re not aging you’re dead – we are privileged to grow older”. So why are there difficulties in recruiting young people, and students in particular, to work with older populations? Ageism, like negative attitudes or death anxiety, are big factors. So is exposure. Young people who have grown up around older adults, or who have teachers or parents who work with older populations, tend to be a lot more receptive.

“I attribute a lot of my interest in aging to my great-aunt Lila. My mom was her primary caregiver when I was growing up, so she spent a lot of time at our house and I spent a lot of time with her. I found her to be fascinating. She wore a wig and I saw her without a wig which was fascinating when I was nine. She told me stories about having a pet rat when she was my age and it was amazing to think about her having ever been my age. I had good relationships with my grandmothers and I had older adults in my life a lot when I was growing up.”

Geropsychology, as a relatively new field, is an exciting one. There is an enormous breadth of research that has yet to be done, and there are countless opportunities to work with people whose life experiences, wisdom, and stories are both fascinating and instructional. They represent a living history of a time the rest of us did not experience, and have lived lives we can’t imagine. Dr. Strong says it’s impossible to overestimate how rewarding this work can be.

“This is a group that has been marginalized, that doesn’t have much of a voice, and when you take the time to interact with them they are so grateful. They have so much wisdom and so many experiences that I can’t help but learn from them. They’ve lived in times and done things that will never be available to me.

The community of Geropsychology and gerontology is such a welcoming one, because we want people to work with older adults. And because the people who end up in that field are warm and welcoming by nature. It’s just a wonderful professional home.”

We need the Big G experts to learn more about aging and about creating a welcoming, flourishing, and healthy society for people as they get older. We also need everyone else to develop lowercase g competencies, so we too can be part of the solution. As each of us gets older, we will want the world around us to change so that we can continue to build community and live meaningful, impactful lives for as long as we are around. This is how we do it.

Research papers:

Mental health and music group development and evaluation (with manual published in the appendices)

Two articles on cognition in older adult musicians

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0278262622000410

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0305735618785020

And one recent on attitudes towards older adults

Laura Thomas-photo by Erik McRitchie

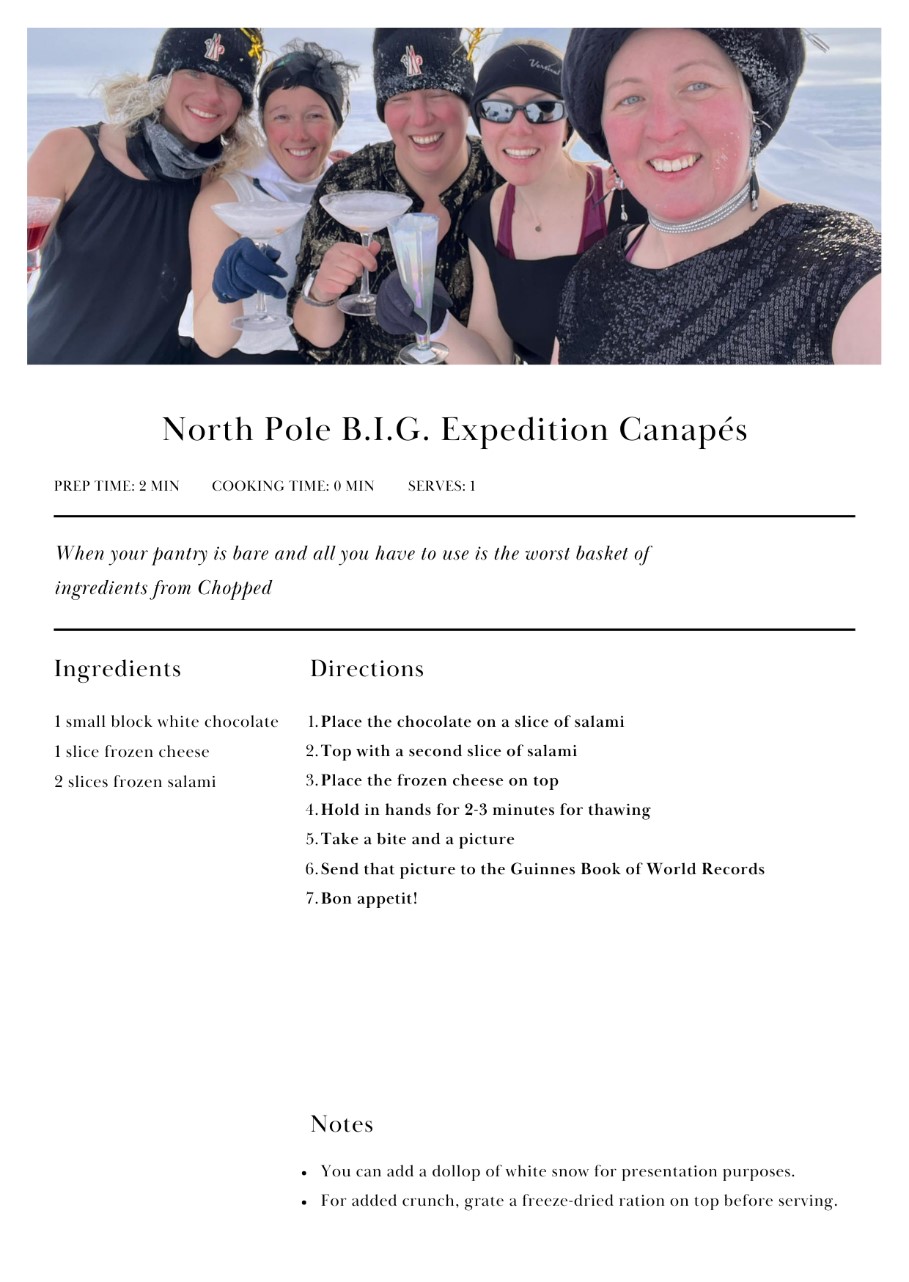

B.I.G. at the North Pole photo by Edel Kieran

Training astronauts for space flight requires a huge team, including psychologists who can help to prepare them for the close quarters and isolation for long periods of time. Laura Thomas is not only one of those psychologists, she has also experienced similar close quarters and isolation with all-female expeditions to places like the North Pole.

We kick off 2025’s Psychology Month: Women in Science with a look at Laura’s work, her travels, and the requirements for setting a Guinness World Record!

I am often in awe of the people I interview, many of whom are remarkably accomplished and doing work that matters to the world. At times, I’m even a little bit envious, in that I would love to have been a part of some of those projects. I confided as much in Laura Thomas toward the end of our Zoom meeting, but told her she is an exception. Not that I’m not in awe of everything she does – I certainly am. But I am not the least bit envious. I would love to have been a part of the World’s Most Northerly Cocktail Party (scroll down for canapé recipe). But very few forces on Earth could have convinced me to be part of the intrepid group that skied, camped, and braved the shifting ice of the North Pole for days in order to get there.

Laura Thomas, on the other hand, couldn’t wait. In 2016, she was a counseling psychologist in the UK and an afficionado of adventure tourism. She began to take an interest in extreme environments, and attended a lecture by British explorer Felicity Aston, MBE. They chatted, and before long Laura was joining her on a trekking trip to Ethiopia. A few years later, she was headed to the North Pole, living in Calgary, and going in a whole new direction with her career.

Trekking to the North Pole seems like a long way to go…because it is. Consider this – the distance to the current magnetic North Pole from Alert, Nunavut, the northernmost inhabited place on Earth, is a little over 800 km. The distance from the Earth to the International Space Station is only 400 km.

Do you ever look up at the ISS as it passes over us, and wonder what the astronauts are doing? Some kind of science, one assumes, and lots of freeze-dried cuisine? Some kind of exercise that looks like that scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey? As Canadians, we know that some of them practice David Bowie tunes on guitars, since there’s no way Chris Hadfield was able to do that performance without practice.

Laura knows what the astronauts are doing. Or, at least, what they could do. And how they can do it, what with the long months of isolation, the forced intimacy of close quarters, and the physical changes one undergoes while in those conditions. Laura studies people, and their behaviour, in extreme isolation.

Laura is the co-founder of PARSEC Space, a new company that exists to train commercial space operators. She works alongside scientists, pilots, and engineers from the likes of NASA, ESA, and the military to select, train, and develop the next generation of astronauts. These will not necessarily be space travelers who will be going to the ISS. There are many other plans for space exploration. Says Laura,

“Rather than space tourism, per se, we’re focused more on research and payload specialists. People who are going to go up and offer their expertise for various projects and research that’s being done in space. The thing about government agency astronauts is that it takes a huge amount of time and money to train them. And they’re generalists. They’re not necessarily the experts in the kinds of technology they’re trialing or the experiments they’re running up there. In the future there will be a lot more space research.”

Pharmaceutical companies, for example, want to test new medications in space. Things act differently in space because of the conditions. In microgravity, bacteria grows differently. There could be a lot of benefits from observing how things grow in the absence of gravity. Manufacturing companies are also leaning toward testing their products and systems in space. NASA is looking to build a permanent base on the moon, which would undoubtedly include a significant research facility.

When that happens, PARSEC will be there to train the astronauts who will go there, and Laura will be assessing the mental fitness of participants and training them to handle the rigours of space travel.

“The qualities that are desirable in an astronaut have changed a little over the years. We call it the ‘new right stuff’. Previously, missions were relatively short, so you needed people with the technical skills to get the job done. But if you’re looking at people surviving and thriving in space over the longer term, with that level of extreme isolation and confinement, you need to look at how people cope. Their innate resilience, their capacity to cope with different types of stressors, how well they get on with other people, how well they function within a team. The so-called softer side, the personality-related traits, become much more important.”

Laura can’t just go up to space to watch people and guide them in that exact environment, at least not yet, so analogue environments on Earth (those with the most similarities to conditions in space) will have to do. Subterranean cave systems, remote jungles and mountains, and of course polar regions. Laura, for example, was the crew psychological officer on one such “analogue” in the Mojave Desert where they were isolated for ten days.

“It was really interesting, we were in this habitat, which was a series of pods, basically. Eight women by ourselves, isolated in the Mojave and living like astronauts. We had a medical officer, an engineering officer, a crew commander. Our daily routine involved exercises and activities that we would need to do as astronauts.”

While there, Laura observed and assisted her crewmates to ensure everyone was coping well, identifying the best interventions and adaptations in that setting. It was the first ever analogue that was all-female, attracting scientists from all over the world. There were crew members from Jordan, New Zealand, the U.S. and elsewhere. It enabled Laura to further her research into salutogenesis in analogue environments. Salutogenesis refers to a focus on the factors that promote health, well-being, and positive outcomes for people.

A lot of people have very positive experiences in these kind of environments. Often, astronauts who go into space can look back on the Earth through the Cupola windows, which can create a profound feeling of transcendence. They come back to Earth with a different sense of the planet’s beauty and it’s fragility and develop more compassion for humanity. This is called the ‘overview effect’, and it lasts much longer than just the moment an astronaut looks out the window of a spacecraft. States of extreme awe and transcendence have also been seen in terrestrial-based analogues.

“You can see from a distance that the Earth is all landmass and water. We can’t tell where the border to one country begins and another ends. It gives you a real conviction that we’re all part of the same thing.”

There have also been reports of increases in feelings of personal strength, better stress resilience, and long-term physical health outcomes. Sometimes, the more stressful the situation is for the participants, the more profound the changes to their psyche. Laura says it’s almost like there’s a threshold of stress that must be met for the more positive benefits to take effect.

It’s hard to imagine an expedition more stressful than one to the North Pole. In 2024, Laura and her fellow explorers, all women, set out to take ice, snow and water samples at the 1996 position of the magnetic North Pole. The B.I.G. (Before It’s Gone) expedition had been planned since 2020, but delays caused by COVID and the Russian invasion of Ukraine meant that some team members had to drop out and Laura could step in.

Their team, led by British explorer Felicity Aston, MBE, trained in cross-country skiing in Norway and Iceland for weeks. Then they flew into Iqaluit, then to Resolute Bay, then to Isachsen – an abandoned weather station from the 70s which was the closest landing strip to the magnetic pole. Each of those plane flights was delayed by severe weather, which truncated the time they had to set off. On skis, pulling their equipment in their sleds, they headed toward the pole.

There were more delays along the way. Terrible weather had them stuck in their tents for almost three days. Despite being physically exhausted and seriously dehydrated, they had to push forward anyway to get ahead of an incoming storm. The team was always on lookout, for both shifting ice and polar bears. Says Laura,

“It’s an experience, but it’s hard. Being in those environments, anyone will tell you it’s hard. You need to have the right gear, but even then it’s brutal. You’re basically out there where everything’s trying to kill you. The cold, the sea ice, and even polar bears. When we got to Resolute Bay, the locals told us it was polar bear mating season and we’d definitely have an encounter with them.”

Along the way, the team collected data. They showed that all kinds of different microplastics have made their way into the North Pole ice, as have heavy metals like lead, and, importantly, black carbon. Black carbon is what is produced when we drive cars, run industrial plants, and experience wildfires. Its presence in the arctic ice is quite serious – the small black particulates make the ice melt faster than it already is, and this speeds up the effects of climate change.

Laura gathered data as well, for her salutogenesis project as she learned even more about how people respond when pushed to such extremes. Sadly, they didn’t quite make it to the magnetic north pole, thanks to the weather delays and shortened time frame for the trip. But they did stop to set a Guinness world record!

World records, at least as adjudicated by Guinness, are kind of a funny process. You have to contact them directly ahead of time, laying out your intention to break some previous world record, or create a new one (hi Guinness, it’s me! I plan to make the world’s largest Build-A-Bear, would that qualify for inclusion?) Then they have specific criteria that must be met in order for you to lay claim to that record.

And so it was that the B.I.G. team, in addition to their scientific equipment and survival gear, carried cocktail glasses, cocktail dresses, and a device to play music all the way to the North Pole with them. One of the trip’s sponsors was an alcoholic beverage company (Axia Spirit), and this was a tip-of-the-hat to them. But according to Guinness, it is not a cocktail party without tunes, a table, cocktail attire, and canapés.

An adventurous spirit, a quest for knowledge and experience, and a determined toughness made Laura Thomas an ideal candidate for a skiing trip to the North Pole. A dedication to comfort, a lack of physical fitness, and a penchant for variety in my cuisine made me the ideal person to sit at home and write about it. And it’s fun to write about a “space psychologist”. Several years ago, there might have been a handful of those on Earth. Now, as space is opening up, so are the opportunities for a vast array of experts to ensure the safety and effectiveness of this new enterprise.

Laura’s training as a psychologist and passion for research have served her well here on Earth. She is working on projects that shed light on some of the world’s most serious problems. And it is those qualities and qualifications that will serve the next generation of explorers. The ones who will head into the most unexplored regions of our world – those beyond our world. They will be in a position to succeed, thanks to a dedicated team of experts to help them with their work, and Laura to help them with their minds. Who better than someone with her kind of experience to accomplish B.I.G. things?

Maureen Plante was the recipient of a 2024 CPA Indigenous Psychology Student Award for her work at the University of Calgary studying disrupted orders of eating from an Indigenous perspective.

Maureen Plante est Iroquoise-Crie-Métisse du côté de son père, tandis que sa mère est d’origine allemande. Ayant souffert d’un trouble de l’alimentation à l’adolescence, elle a été amenée à faire une recherche de maîtrise à l’Université de Calgary, qui portait sur les troubles de l’alimentation dans une perspective autochtone. Elle a grandi en s’identifiant avant tout comme Crie, une communauté autochtone qui se souvient encore de l’époque où les bisons parcouraient les plaines canadiennes en vastes troupeaux quasi infinis.

L’éradication des bisons des plaines occidentales de l’Amérique du Nord au cours des 18e et 19e siècles est une illustration frappante du conflit entre les traditions autochtones et la philosophie coloniale européenne. À la fin des années 1700, on estimait à 30 millions le nombre de bisons vivant dans les grandes plaines nord-américaines.

Jusqu’à cette époque, les peuples autochtones de l’Ouest canadien vivaient aux côtés des bisons, qu’ils chassaient pour leurs fourrures et leur viande. La terre était un partenaire partagé qui assurait la subsistance de la population. Lorsque les colons sont arrivés, ils ont introduit une mentalité différente, celle de l’exploitation des ressources et du capitalisme. L’abondance de bisons des plaines et de bisons des bois permettait de réaliser d’énormes bénéfices sans grand effort, et la chasse a commencé sérieusement.

Pour les populations autochtones, cela signifiait qu’elles devaient elles-mêmes s’adapter à la nouvelle réalité. Elles devaient désormais entrer en concurrence avec les chasseurs blancs pour le moindre animal et étaient contraints, pour survivre, de passer d’une relation de coopération à une relation d’exploitation des ressources. Beaucoup sont devenus des chasseurs de bisons nomades, vendant des peaux et d’autres objets en échange des nécessités de l’existence. La nourriture n’était plus une partie évidente et intégrante de la vie, comme l’air et l’eau, mais une marchandise.

Il serait exagéré d’établir un lien direct entre l’éradication du bison et les troubles de l’alimentation qu’a connus Maureen Plante quelque 200 ans plus tard. Mais en même temps, il ne faut pas négliger ce lien. Ces dernières années, les traumatismes historiques ont fait couler beaucoup d’encre, notamment en ce qui concerne les souffrances subies au fil des siècles par les peuples autochtones du Canada. Mais nous commençons à peine à effleurer la surface de ce que cela signifie vraiment, et la façon dont les traumatismes historiques nourrissent les problèmes que nous observons aujourd’hui.

Maureen a grandi dans une très petite collectivité située à l’extérieur d’Edmonton, où l’accès aux services était très limité. Lorsqu’elle a développé un trouble de l’alimentation à l’adolescence, il y avait très peu de ressources dans sa région immédiate, et même dans les centres urbains voisins, il n’y avait guère de soutien centré sur les Autochtones. À l’âge de 16 ans, Maureen s’est juré d’aider d’autres personnes qui avaient le même type de comportements alimentaires perturbés, et elle n’a jamais cessé de poursuivre cet objectif depuis.

Elle a obtenu son baccalauréat avec spécialisation en psychologie à l’Université MacEwan d’Edmonton, sa maîtrise à l’Université de Calgary et elle prépare actuellement un doctorat en psychologie du counseling à l’Université de l’Alberta. Au cours de cette période, elle a travaillé au Eating Disorder Support Network of Alberta de différentes manières, notamment comme bénévole. Bien que Maureen ait toujours parlé ouvertement et avec vigueur des comportements alimentaires perturbés, ce n’est que lorsqu’elle a obtenu sa maîtrise qu’elle a pu commencer à explorer les points de vue autochtones dans le cadre de son travail.

À cette fin, Maureen a travaillé avec des femmes autochtones – thérapeutes, psychologues, travailleuses sociales – qui proposaient des thérapies fondées sur le modèle IFOT. L’Indigenous Focusing-Oriented Therapy (thérapie autochtone axée sur l’individu) est une modalité thérapeutique historiquement pertinente et adaptée, qui adopte une approche de la guérison basée sur les forces. Elle correspond à ce que font les chercheurs et les praticiens autochtones lorsqu’ils travaillent avec des Autochtones. La « grand-mère de l’IFOT », Shirley Turcotte, a travaillé avec Eugene Gendlin, créateur de la FOT, pour créer cette approche, estimant que les points de vue autochtones étaient négligés, en particulier la relation que nous entretenons avec nos ancêtres et toutes nos relations.

Maureen, qui prépare actuellement son doctorat, a déjà reçu le Prix pour les étudiants autochtones 2023 de la SCP pour le travail qu’elle accomplit et qui cherche à approfondir tout ce qu’elle a fait jusqu’à présent.

« J’ai entendu les praticiens qui dispensent l’IFOT, je veux entendre dorénavant les Autochtones. Certaines femmes vivant dans des centres urbains m’ont raconté qu’elles avaient vécu des perturbations des comportements alimentaires et qu’elles s’étaient parfois rendues à l’hôpital pour y recevoir des soins. Cela ne les avait pas aidées. Je souhaite également comprendre le rôle que jouent les traumatismes historiques dans le développement de comportements alimentaires perturbés chez les Autochtones, car j’ai l’impression que cet aspect a été négligé.

Les troupeaux de bisons n’ont jamais été près de se reconstituer complètement, et on estime aujourd’hui à 20 000 le nombre de bisons sauvages vivant en Amérique du Nord, soit 0,0007 % de ce qu’il était il y a 200 ans. Pendant ce temps, les communautés autochtones qui pratiquaient l’agriculture depuis des centaines d’années ont dû modifier leurs pratiques, car l’accent était mis désormais sur les monocultures.

Autrefois, les arêtes des poissons de la rivière fertilisaient les haricots qui fournissaient de l’azote au maïs. Les gens se nourrissaient de poissons, de haricots, de maïs et de courges qui étaient cultivées autour des cultures pour les protéger des animaux affamés. Lorsque le gouvernement canadien a commencé à construire un chemin de fer à travers le pays, la marchandisation de l’agriculture a été l’un des moyens qu’il a utilisés pour priver les populations autochtones de leurs droits. Dans cette région, on cultivait désormais de l’orge, et uniquement de l’orge. Dans cette autre région, c’était du lin, dans la région voisine, c’était du canola, tout cela dans le but d’expédier et de vendre le produit.

Les communautés autochtones agraires ont dû soit modifier leurs pratiques pour participer à ce nouveau paradigme, soit se déplacer vers des zones moins fertiles pour essayer de pratiquer une agriculture de subsistance, en espérant pouvoir cultiver suffisamment pour faire vivre leurs familles d’un hiver rigoureux à l’autre. Toutes n’ont pas pu le faire.

L’une des notions centrales de l’IFOT c’est qu’en se concentrant sur soi-même, on peut trouver son propre « remède », c’est-à-dire ce qui fonctionnera pour soi pour traiter ses problèmes de santé mentale. Lorsque Maureen a fait sa maîtrise, elle a été initiée à cette pratique. Pour elle, cela a fait remonter beaucoup d’herbe et de blé, et elle a découvert que le blé était son remède. C’était une prise de conscience étrange, car son trouble de l’alimentation faisait que son cerveau lui disait que le blé était mauvais. Cette révélation a changé son point de vue sur sa relation avec la nourriture et l’a éclairée sur le croisement entre l’identité autochtone et les comportements alimentaires perturbés.

« L’une des choses les plus importantes qui ont été partagées par les aînés et les porteurs de connaissances est la suivante : “Le DSM-5 [Manuel diagnostique et statistique des troubles mentaux, la classification standard des troubles mentaux utilisée par les professionnels de la santé mentale] est basé sur des catégories dans lesquelles on retrouve différents types de troubles du comportement alimentaire (anorexie, boulimie, etc.).” Les gardiens du savoir autochtone affirment que ce type de pensée eurocentrique rompt l’interconnexion. Ma recherche de maîtrise soulignait vraiment l’interconnexion et l’enracinement dans le contexte du colonialisme. Depuis le contact avec les Européens et tout au long de l’histoire, l’accès des peuples autochtones aux aliments traditionnels et aux droits de chasse, entre autres, a été très controversé. Beaucoup de choses se sont passées ici, qui ont modifié notre relation avec la nourriture et notre lien avec la terre. Comme la Loi sur les Indiens, des lois qui ont des répercussions sur notre relation. Un aspect sur lequel j’ai vraiment insisté dans ma recherche de maîtrise était la nécessité de commencer à changer notre relation avec le terme « troubles de l’alimentation » afin de ne pas les pathologiser, mais plutôt de les situer dans le contexte du colonialisme ».

Dans le cas des comportements alimentaires perturbés, le poids, la forme du corps et l’idéalisation de la minceur sont des préoccupations très présentes, du moins, en Amérique du Nord où le DSM-5 est le plus utilisé. Maureen est curieuse de savoir si cette idéalisation de la minceur est un phénomène qui touche toutes les cultures. Il est difficile d’obtenir des données sur les taux de comportements alimentaires perturbés chez les Autochtones et sur la répartition entre zones rurales et urbaines, car la plupart de ces données proviennent des programmes de traitement, auxquels très peu d’Autochtones sont inscrits. Certains chercheurs non autochtones affirment qu’il faut que les Autochtones s’expriment davantage sur le sujet.

« Beaucoup d’articles que j’ai trouvés parlent encore du DSM-5, du taux de prévalence, etc. La dimension narrative fait défaut, et nous ignorons un grand nombre de choses, ce qui, je le crains, nous amène par inadvertance à mettre des étiquettes sur les Autochtones (ou même sur les non-Autochtones). »

Maureen est en passe de devenir une voix autochtone forte sur le thème de la perturbation des comportements alimentaires. Son histoire se nourrit de son expérience personnelle, mais aussi de la décimation de la population de bisons, du passage à l’agriculture de subsistance, de la famine qui régnait dans les pensionnats et de toutes les autres indignités qui ont bouleversé la relation des peuples autochtones avec la terre et leur nourriture. Son avenir se nourrit de cette histoire, mais aussi de l’IFOT, du DSM-5 et d’un parcours universitaire remarquable et primé dans certains des meilleurs établissements d’enseignement supérieur de l’Alberta. Nous sommes impatients de découvrir les enseignements précieux que cet avenir radieux nous apportera!

Questions pour faire connaissance

Avez-vous un livre préféré?Je crois que oui… Les Méditations de Marc Aurèle. Il y a quelque chose dans ce livre qui fait vraiment réfléchir, qui est philosophique et qui donne de bonnes leçons de vie. Je suis quelqu’un sur les médias sociaux qui en parle beaucoup, et cela m’a donné envie de m’y plonger. Je l’ai lu entre ma maîtrise et mon doctorat, et je me concentrais vraiment sur la psychologie. J’ai trouvé que la TCC comportait un élément de questionnement socratique, et ce livre semblait intéressant à lire dans cette perspective. Lors du congrès de la SCP de 2022, j’ai assisté à une présentation donnée par deux messieurs sur le stoïcisme et la TCC, qui m’a fait penser aux Méditations et m’a donné l’impression d’une certaine convergence de vues avec les miennes!

Si vous pouviez être une experte dans un autre domaine que la psychologie, quel serait-il?

Quand j’étais plus jeune, je voulais devenir biologiste marine. J’aime les animaux, et je suis folle des raies. Récemment, j’ai beaucoup lu sur le comportement des loutres. Je sais que des recherches sont en cours sur les loutres et que les chercheurs travaillent avec les communautés autochtones pour savoir comment favoriser les relations entre humains et loutres.

J’ai lu une étude sur les loutres et les dauphins, car les loutres et les dauphins peuvent tous deux utiliser des outils, mais les loutres ont précédé les dauphins en ce qui concerne l’utilisation d’outils.

Avez-vous un sport préféré?

Non, pas vraiment, mais j’ai commencé récemment à regarder le hockey avec mon copain. J’aime aller au centre d’entraînement physique et être active, alors je fais de la musculation et d’autres choses de ce genre.

Si vous pouviez passer une journée dans la tête de quelqu’un d’autre, ce serait qui?

Je pense que c’est parce que je suis à ce stade de ma vie, mais je dirais mon conjoint. C’est un charpentier certifié Sceau rouge et son travail est complètement différent du mien. Il travaille de ses mains, c’est un as des mathématiques, et il est capable de visualiser un espace et de savoir comment y configurer les choses. C’est un travail difficile, et j’aimerais vraiment passer une journée dans son cerveau pour comprendre son univers et sa façon de voir les choses. J’admire les gens de métier, qui font des tas de choses extraordinaires, et je reconnais que je ne suis pas très douée pour tout ça! En outre, en tant qu’êtres humains, nous ne savons pas vraiment comment nous sommes reçus par les autres!

Quel est le concept psychologique qui vous a le plus surprise lorsque vous en avez entendu parler pour la première fois?

J’ai fait un baccalauréat en psychologie sociale, et j’aime encore beaucoup cette discipline. Je pense à l’étude de la prison de Stanford, l’expérience de Asch, qui font ressortir, en quelque sorte, le côté sombre de l’expérience humaine, et je trouve tout cela vraiment fascinant. Aussi, tout ce qui a trait à la personnalité me fascine, comme le modèle de personnalité à cinq facteurs. En ce moment, je lis des travaux de chercheurs qui parlent de cela dans le contexte du travail, des études, etc.

Si vous ne pouviez écouter qu’un seul musicien ou chanteur jusqu’à la fin de votre vie, ce serait qui?

J’aime beaucoup la musique classique, alors je répondrai Bach.

Trinity Stephens was the recipient of a 2024 CPA Indigenous Psychology Student Award for her unconventional work as an undergrad at UBC.

There are certain things we expect from other people in terms of their behaviour. We expect people to turn right when their right turn signal is on. We expect that when we order a coffee that the barista will put it in a cup, and that fellow bus riders will refrain from doing chin-ups on the hand-hold bars. Or, that when we get on an elevator, everyone will face the door and the buttons, avoid eye contact, and ride up to their floor in silence. And these expectations are mostly confirmed by others. Unless, perhaps, you get on an elevator with Trinity Stephens.

“Even when I was a child I never did what other people did, but it was when I became a psychology student that I realized how odd it is. We had this one social psych class where the prof sent us on missions. Like, go into society and break social norms. So for a week straight, I would go into the elevator and face everyone. While everyone faces the one direction, I was looking the other way. Just forcing myself to overcome the idea that I had to do what everyone else was doing. People hated it, especially if I was with my friends. They got really annoyed with it, and I could see the anxiety it provoked in people.”

Trinity is going into her final year of her undergrad at UBC. She’s Mi'kmaq, Métis, and Jamaican, and recently received a CPA Indigenous Psychology Student Award for her work in school – where she is doing a bachelor of arts with a psychology major, and also a minor in law & society and a minor in education.

Ever since she was a child, she had an instinct to help other people. A psychology course in high school intrigued her, and she became rapt with the idea of learning about the actions of people, and the motivations for those actions that often go unnoticed. Soon, she was looking to start an undergrad in psychology, with the goal of one day becoming a counselor for people in her community.

Trinity visited the UBC campus and immediately fell in love. Coming from the chaotic, bustling environment of Toronto, the feel of a community network, in close proximity to nature was appealing – and something far different from her familiar hometown feel. She says she feels peaceful while she’s there.

“There are actual forests on campus, and there are cherry blossoms all over, and there’s even our own Zen garden that’s really well kept up. I thought if I’m going to spend any time anywhere doing anything, I want it to be for psychology and I want it to be here.”

While at UBC, Trinity has been working at the Alpine Counseling Clinic in Vancouver as a neurofeedback technician. She works on weekends, where she sees anywhere from 4-12 clients a day, ranging in age from 4-80 years old. As Director of Feedback, she’s providing what she calls a Western form of healing, a dynamic she finds very interesting. She has 30-minute sessions with clients helping them “connect with themselves”, honing in on how they’re feeling inside and what’s causing stress and anxiety in their lives.

The connection between Western ways of healing and traditional ways is a subject of particular interest for Trinity. She is enthusiastic about both and believes that the one can enhance the other and vice versa.

“My main goal was to be a counsellor for BIPOC people, specifically in Black and Indigenous communities. There’s a lot of stigma around therapy because it’s something we’re not really used to, but it is something all our ancestors have done. So I thought that by being able to study the Western side would give me an advantage because I already have a lot of my ancestral and holistic knowledge. Even while studying psychology, I’ve noticed there’s a lot of overlap with traditional medicine and traditional ways of healing. It made it a natural thing for me to learn.”

Her love for UBC and the campus community led Trinity to apply for her Master’s program there – and only there. She was not accepted, so for the time being she is considering some other options before once again trying for her Master’s. One option might be becoming a life coach for post-grads, recognizing how much of a whirlwind it is for them right now. Another option is to become a doula.

Doulas help mothers through their pregnancies. They work with them up to the point of giving birth, and also work with them after the birth to help with things like feeding and support. Says, Trinity, “it’s especially helpful in Black and Indigenous communities to help mothers with their birthing journeys, reducing trauma for both the mother and the child. I think that would be a really nice accent to my resume when I do apply for the Master’s in the future. It can also be really expensive so I want to have a sliding scale for people who might not otherwise be able to afford it.”