February is Psychology Month

Psychology is rooted in science that seeks to understand our thoughts, feelings and actions. It is a broad field – some psychology professionals develop and test theories through research while others work to help individuals, organizations, and communities function better. Still others are both researchers and practitioners.

Psychology Month is celebrated every February to highlight the contributions of Canadian psychologists and to show Canadians how psychology works to help – people live healthy and happy lives, their communities flourish, their employers create better workplaces, and their governments develop effective policies.

Want To Get Involved?

- Follow us on Instagram @canadianpsychological where a new spotlight will be posted every week in February.

- Follow @canadianpsychology.bsky.social on Bluesky and LinkedIn or “like” us on Facebook and share the stories and spotlights.

- Download our poster for your office or for use in your Psychology Month activities.

- Follow the CPA podcast Mind Full on SoundCloud, YouTube, or wherever you get your podcasts for a new episode every Thursday during Psychology Month

This is Psychology

Psychology impacts us in obvious ways, but also in more subtle ones. For this year’s Psychology Month, the Canadian Psychological Association is highlighting the areas in our lives that have been shaped and enhanced by psychological science and clinical practices. THIS IS PSYCHOLOGY.

If you have events planned for Psychology Month, let our Communications Specialist, Eric Bollman, know about them – email Psygnature@cpa.ca to have your event included in the CPA’s social media for the month. Please download the poster here: Psychology Month Poster (PDF) and share with your networks! Use the hashtag #PsychologyMonth.

Applying for a new job can be a nerve-wracking endeavour. Industrial/Organizational psychologist Dr. Nicolas Roulin from St. Mary’s University shares some insights into the process, illuminating the ways companies go about recruiting and the contributions of psychology to that exercise. Madeline Springle is a Ph.D. student at the University of Calgary, and she shares some tips for job-seekers about preparing for that important interview.

Most names in the following article have been lifted directly from the 1998 classic Office Space. The real people are Dr. Nicolas Roulin, a professor of Industrial/Organizational (I/O) psychology at Saint Mary’s University, and Madeline Springle, a job interview coach and a Ph.D candidate in I/O psychology at the University of Calgary.

Joanna was dissatisfied with her job. In just five months working there, she had realized how toxic the work environment was, and she realized that continuing to work there would have a detrimental effect on her mind and her soul. People were quitting all around her. Their work was being added to her own, without a raise in salary or so much as an acknowledgement of the increased workload. She knew she had to start exploring new opportunities.

Joanna updated her resumé and started looking on a series of employment sites. Although she felt that most anything would be better than her current workplace, she didn’t want to make the same mistake she had made when she accepted this current job. She was determined to find a company that was not only a good fit for her skills, but one where she could envision herself pursuing a career over the long term.

The first company whose job ad spoke to her was Initech, and they were right up her alley. They were asking for the database management skills she possessed, they were located a reasonable distance from her house, and they offered flexible office hours that would allow her to work from home whenever her kids were under the weather or her wife had to take the car to her own job. She wrote up a cover letter and sent off her application.

At Initech’s head office, HR manager Samir came in after the long weekend and checked his inbox. There were 209 messages, all from people applying for the open position! How on Earth was he going to get through all of these resumés on his own? Ah! He thought. I’m sure artificial intelligence can help here. He quickly pulled up a generative AI program, and plugged in the resumés of the company’s top-performing employees. He then had the program review all 209 resumés that had been sent in, and asked it to choose the top 10.

Although Samir wasn’t aware of it, the AI program had determined that two things, above all others, determined the quality of a Initech employee. Most of the top employees had included their middle names on their resumés. And many of them had been part of their high school bands. Joanna doesn’t play an instrument, and had not considered adding her middle name to anything. No one at Initech ever saw her resumé. Nobody contacted her to let her know they had received it.

Dr. Nicolas Roulin is an I/O psychology expert who was part of the team that conducted the search for the CPA’s new CEO, the team that chose Dr. Lisa Votta-Bleeker after Dr. Karen Cohen’s retirement. He says,

“AI has pros and cons, broadly speaking. If you use the right AI tools, it can make things faster, cheaper, and easier for an organization. In I/O psychology, recruitment often starts with a job analysis. The person in charge of the hiring will want to talk to the people who are currently doing the job, their supervisors, and maybe their subordinates. This is to figure out what exactly the job is about. What makes those employees effective, or less effective? What are the key issues they’re facing in that job? This might involve speaking with five, six, or even ten employees in order to get a good understanding. This can be quite time-consuming. If you use AI in an effective way, and understand how to implement it, you might be able to get similar results without having to speak with as many people.

The problem is that if you’re using the wrong AI, or the AI you’re using is built on very limited information or data, then you can get a situation where it tells you to look for three-named trombone players. If you have a very limited pool of data to train the AI, then it will do nothing more than replicate the biases that currently exist in that pool. If you are feeding in the data from all your employees, and most of them are middle-aged white men who play beer league hockey, then it’s likely your best performers are middle-aged white men who play beer league hockey. With a larger database, for example one of the large language models that are out there, running into a problem like this is a lot less likely.”

Joanna was ghosted by Initech, but she didn’t sit around to wait. She got right back to work and applied to a job with Initrode, which seemed to be looking for someone with her exact skill set. This job posting included a salary, and it was offering 25% more than she was currently earning. This time, she got a reply!

Initrode’s HR specialist Nina wanted Joanna to provide video answers to a series of questions. This next step was a one-way video interview, something Joanna had never heard of before. She was to record herself answering questions, looking at a camera, but there would be no interviewer there. How would you even go about preparing for that? Why would a company want that?

Madeline Springle is a job interview coach who hosts the Master Your Interview YouTube channel. She says companies do these kind of interviews because they mean every candidate gets the same questions, they all have the same amount of time to prepare and respond, and that this is a tactic that helps streamline the process when a company is conducting a high-volume hiring process.

“Companies likely understand how little candidates like these types of interviews, but they’re here to stay and there must be a reason. The purpose of the one-way video interview is to establish the first line of contact. It usually replaces the phone screening that was once the norm. The HR department would call the candidate to ask a series of screening questions and verify a few details. This would always happen during the work day. So would you rather have someone evaluating your video interview at a time when they’re feeling fresh and on their game, or call you when they’re at the end of a long day and this is the only time slot that could work for them?

The one-way video interview is really about deciding ‘should we move this candidate to the next round?’ You’ve submitted your resumé, then you get that video link. It’s a way to show you’re human, you can do the things you said you could do in your cover letter, and are you able to speak clearly about yourself.”

Dr. Roulin adds,

“One of the advantages of an asynchronous video interview is that the applicant can record their interview from any location, and at a time that’s convenient for them. If you have someone who already has a 9-to-5 job, they would previously have to take an afternoon off from that job to attend the interview. Now, they can record it at 10 pm if they like. That flexibility opens more doors to more people who might otherwise not have been able to do an interview in-person.”

Joanna had never talked directly to a camera to record something like this before. She made sure her background was clear, added a little wall hanging that really tied the room together, removed any distractions, and crafted her answers to the questions. She wrote them out and put them on a board just behind her camera, so she could read them and be sure her answers came out with the right wording. It felt robotic, but she guessed that was to be expected.

Nina sent her a kind, but brief email. Initrode had decided to go in a different direction.

Madeline says,

“There is such a fine line between extensively practicing and preparing, versus over-preparing and feeling like a robot when you deliver. In order to not sound overly rehearsed, try creating novelty in your response – something that will keep even you on your toes. At the core of this is adding variation to your interview response. The reason you’re feeling robotic is because you’re not emotionally connecting to your story. You’re saying the words, but you’re not actually present. You’re not actually experiencing it again as you share it. This is very common, especially when you’re feeling nervous. What you want to do is this – right before you answer the ‘tell me a time when you…’ question, jump back into that workplace environment. Think about how you felt at the time. Maybe it was five years ago. Who were you back then? Connecting to a former version of yourself will reconnect you to your story, and help you be less robotic and stiff when answering questions.”

Joanna was undaunted. She tried again, and after a while she received a response from a company called Chotchkie And Associates. Thankfully, they went with an initial phone interview for screening, and soon she was on her way to an in-person interview.

Chotchkie And Associate’s hiring manager Bob Porter was looking for a few specific things when he launched the search for their new Senior Database Administrator. Of course, familiarity with database management was essential. But he also wanted to find someone who would be adept at navigating issues that arose over the course of their employment. Specifically, he was thinking about a recent data breach in their customer files that had a catastrophic effect on the company.

Dr. Roulin says it’s quite common now for organizations to seek specific attributes and competencies in their hiring processes based on their own experience with how that role has been handled previously. They identify the most important aspects of the job, and determine what has allowed previous employees to excel there versus those who have been less successful.

“We often use what we call a ‘critical incidence technique’, where we try to identify specific issues that may arise in the role. We then try to understand what makes, say, Anne very effective at dealing with that critical situation, compared to Michael who is struggling to deal with that same situation. From that process we can try to recruit for the characteristics that fit best with the position.”

Bob Porter had determined what the company wanted in their ideal candidate, and prepared for a series of interviews that would be conducted over the course of two weeks. He brought in his colleague Bob Slydell, the manager who would be directly supervising the successful candidate. Some of the interviews would be conducted in-person, some over Zoom. Although Chotchkie & Associates used Teams internally for virtual meetings, Bob was aware that more applicants would be familiar with, and have access to, the Zoom platform.

As Joanna got in the elevator to head up for her interview, she went over some of her work stories in her head. She was nervous. What if they ask why I’m leaving my current job? Am I going to come across as disgruntled if I express how I am…disgruntled? Will I seem like a potentially disloyal employee if I complain about my current employment? And if I come up with a less abrasive version of why I’m leaving, won’t I be lying in my interview?

Madeline says focusing on red flags (your OWN red flags) is a very common mistake job applicants make when they begin an interview.

“Being focused on the negative – why they might not hire you, why they might not like your answer, isn’t helping you. Even worse, the interviewer can pick up on this negativity. Instead, make sure you focus on your ‘green flags’. Why you are qualified, what you bring to the job, and why you want this position. Your mindset going into an interview matters more than you think, so make sure yours is working for you, and not against you.”

Joanna put her doubts out of her head as best she could, and walked into her meeting with the Bobs confident in her ability to describe her past work experiences. It was all going well, and then Bob Slydell asked that dreaded question. “Why do you want to leave your current job?”

Dr. Roulin has studied the way we make impressions in situations like these. He says that while some of the research into making an impression is on the employer side, a lot more has been done on the side of the applicant.

“Some of the work I’ve done is on a topic called ‘impression management’, which has to do with how you can create a good impression in someone else’s mind. An applicant is asked questions, and their goal is to demonstrate that they have the experience and qualifications to perform the job. A good example of this is what we call the ‘STAR method’. For example, when you’re asked a question about an experience you had at work, you can build your answer based on a structure of the Situation, the Task, the Action, and the Result. If an applicant can tell their story with that structure, they can provide more information to the interviewer, and they can make a better impression.”

Joanna gathered herself, and answered. “I want to work somewhere where I can see myself having a career. When I saw your job posting, it looked like there would be good opportunities for advancement. I went on your LinkedIn feed and I saw that Chotchkie & Associates was celebrating Yom Kippur. It reminded me of a time when I was in college, working for the Student Association. There was a program in place that tried to promote inclusivity by adding elements of other religions to the usual celebrations of Christmas, Easter, or St. Patrick’s Day. It wasn’t really working, because it just jumbled up the event and no one really appreciated a nominal inclusion of other symbols in an event that was clearly not meant for them. I started attending celebrations outside the school, like Diwali, Eid, Nawruz. I learned a lot about those events, connected with people and even some of our students in those communities, and with their help I was able to collaborate with them to create specific, distinct events to celebrate their cultures. By the time I left school, many of those events were well-attended by students of all kinds, and I think it helped to build a sense of community. I got the sense that your company had that same sense of community, and that’s why I applied for this position.”

The Bobs looked at each other and nodded. Just the kind of flair they were hoping to see. Joanna got the job.

The COVID pandemic significantly worsened the impact of Canada’s opioid crisis. Toxic drugs became more dangerous as they were more likely to be laced with synthetic opioids like fentanyl. Stay-at-home measures reduced access to supports, supervised injection sites, and social services. And increased isolation, anxiety, and stress contributed to increased use of opioids. Psychological approaches such as cognitive behavioural therapy, contingency management, and behavioural interventions are effective at treating Opioid Use Disorder, and are almost always combined with medications, like methadone.

On this week’s Mind Full podcast we’re focused on one way psychology interacts with the healthcare system, specifically in the field of HIV and AIDS. Our guest, Dr. Sean Rourke, just won a major award for his life’s work, the inaugural Eric Jackman award from the Royal Society of Canada. From the days when an HIV diagnosis was seen as a death sentence to today, when early detection can result in a long and full life, he has been helping Canadians in a myriad of ways.

A diagnosis of cancer will affect each person who receives one a little differently. But it will affect everyone. Not just the person with the diagnosis, but the people around them. Family, friends, and co-workers need help as well. Psychologists can play a central role at every stage, from diagnosis to treatment to end-of-life care.

This week’s Mind Full podcast guests are friends. Bob Wakeham met Dr. Sheila Garland when he joined her study on insomnia in people who had been diagnosed with cancer. Bob shares his story and experiences with us, and tells us how Sheila’s involvement in his life made an enormous difference.

Remember the COVID-19 pandemic? It wasn’t that long ago, but many of us have kind of memory-holed the entire traumatic experience. That said, just because we don’t think about it any more doesn’t mean that the effects aren’t still being felt today. For example, rates of gender-based violence, including femicide, remain elevated above pre-pandemic levels. This is particularly the case in rural communities, and is evident in the attitudes and behaviours of kids in schools.

Canada legalized single-event sports betting in 2021. In the three years that followed, gambling on sporting events in the country rose tenfold. Today, one in five people who bet on sports do so every single day. Our young people are particularly vulnerable, and have been specifically affected by gambling addictions. Bruce Kidd and Steve Joordens are looking to ban advertising for sports gambling in Canada. Senator Marty Deacon has introduced bills to this effect. And Stanford psychologist Dr. Robert Sapolsky explains just what makes sports gambling so dangerous. All four joined us for this Psychology Month look at the dangers of sports gambling and the possible solutions to the problem.

In the early 60s, Bruce Kidd was preparing to represent Canada at the Olympics. He had just received the Lou Marsh award as Canada’s top athlete, and he was speaking at an event and being critical of the way gambling had infiltrated the sports world. At the head table of that event was Paul Hornung, the then-superstar halfback and kicker of the Green Bay Packers. Bruce remembers,

“[Hornung] passed along a note saying he’d like to meet me in the parking lot after the banquet, that being the traditional invitation to a fight, and I made a quick exit out the other way.”

Two weeks later, Hornung was suspended indefinitely by the NFL for gambling. He and Lions superstar Alex Karras had been betting on NFL games and “associating with undesirable persons” (gamblers). Both players were forthright and contrite, and the NFL felt comfortable allowing them back into the league the following year. Despite betting on NFL games, they were both elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton.

Back then, gamblers were “undesirable persons”. They were the shady characters we imagine being played in a movie by Edward G. Robinson. To place a bet, you had to know where to find the illegal bookmaker, sneak in and out of their establishment, leave behind your money, and take your ticket to watch the game in a few days. It was a process. It also gave you time to anticipate your possible win when the Baltimore Colts covered the spread against the St. Louis Cardinals.

Today, things are much different. Handheld devices make it possible to bet not only up to kickoff, but on the distance of the return, whether the next play will be a running play, how many yards the backup tight end will have by the end of the first quarter. As that first quarter ends, you have TV commentators deviating from analysis of the play to analysis of the betting lines. They make suggestions for bets you might want to place before halftime. By the time the game is over, you might have placed eleven bets. You’re unlikely to have won all eleven.

The passion Dr. Bruce Kidd brought to the argument against sports gambling back in the 60s has not abated. Today, as a professor emeritus in Sport & Public Policy and a university Ombudsperson at the University of Toronto, he is doing everything he can to combat the dangers posed by the modern gambling landscape. He has created the website Ban Ads for Gambling to inform and energize the public to fight against the way sports gambling is marketed, in particular to teenagers.

Dr. Robert Sapolsky is a professor of biology, neurology, and neurosurgery at Stanford University. He agrees with Bruce that children are particularly vulnerable to gambling ads and apps.

“Children are absolutely more susceptible to this. We’ve got this very fancy part of the brain called the frontal cortex. It’s the most recently-evolved part of the human brain. We have more of it, and in a more complex way, than any other species. And what it does is things like self-regulation, impulse control, long-term planning, and executive function. The job of the frontal cortex is to calm the more emotive parts of your brain, like the dopamine system, or the parts having to do with aggression or sexual arousal. It tells those other brain areas ‘I wouldn’t do that if I were you. Trust me, I know it seems like a good idea right now, but don’t do it’.

The frontal cortex is the thing that keeps you from doing hideously impulsive things that seem like a good idea at the time, but that you will regret for the rest of your life. So why isn’t the frontal cortex keeping young people from making rash decisions? It’s because the frontal cortex is the last thing to develop. Most of your brain is fully developed around the time you’re getting toilet trained or learning how to walk up and down a flight of stairs. But the frontal cortex isn’t fully online until you’re about a quarter of a century old.

By contrast, the dopamine system is pretty much up-to-speed around the time you’re reaching puberty. This means a dopaminergic engine of disordered and distortive anticipation is there in you, while your frontal cortex is firing on only one cylinder. It can’t regulate it. It’s why adolescents behave in adolescent ways – impulsiveness, sensation-seeking, novelty-seeking, being slow to habituate to negative feedback, that’s what adolescence is about, and it’s mostly because your frontal cortex is still sort of percolating.”

It’s during that time of adolescence when young people, boys in particular, start paying more attention to both sports and their phones. When they watch a hockey game and between periods they see the play-by-play announcer and colour commentator debating what player will score the next goal, adolescents don’t have the same mechanism the rest of us do to slow down the impulse to place a bet based on the seemingly expert advice being dished out by the sportscaster.

Dr. Steve Joordens is a professor of psychology at the University of Toronto. He saw his old friend (and former boss) Bruce on TV, speaking as the Chair of the Campaign to Ban Ads for Gambling, and jumped on board immediately. For Steve, the most insidious thing about ads that encourage sports gambling is not just that they target young people, but that they use psychology to do so. The marketers, the app designers, and the promoters of gambling are all well-versed in methods of persuasion that are derived from psychological principles. Steve wrote an article about it, ‘Sports Gambling and the Weaponization of Psychology’, where he said,

“Society needs to restrict the marketing of sports gambling as soon as possible. It reflects a weaponization of psychology that is designed to create addictions. This is not hyperbole. A headline for The Hill reads ‘Sports betting has risen tenfold in three years. Addiction experts fear the next opioid crisis.’ A Harris Poll from November 2022 reported that 71% of those who bet on sports did so at least once a week with 20% betting once per day! The website suicide.ca has an entire page dedicated to helping those with gambling addictions.

Sports gambling is so dangerous because of the psychological power of random rewards. When players gamble, they lose more often than they win, However, the random nature of wins means they never know when that next win is coming. They start chasing that next win. At the neuroscientific level, the hormone dopamine is released when one is chasing a desired outcome and this release feels good, literally the thrill of the chase. Each loss can make the player feel one step closer to that next win, which always feels like it’s just around the corner. This makes the player ‘resistant to extinction’. Once they start, they don’t want to stop, especially after a string of losses.”

Dr. Sapolsky describes the mechanism by which dopamine encourages certain behaviours. Dopamine is the neurotransmitter that regulates pleasure, and many of us are familiar with dopamine experiments done with animals like rats or monkeys. For example – a light goes on, which is the signal to press a lever, and that pressing of the lever distributes a treat of some kind. But the dopamine isn’t released when the treat is revealed, or when it is consumed. And it isn’t triggered when the lever is pressed. Instead, the dopamine rush felt by a rat or a monkey or indeed a human being happens when the light comes on. It’s the anticipation of the reward, not the reward itself, that activates our pleasure centres. He explains further.

“Dopamine goes up when the signal comes on. You see the light and you think ‘oh, this is going to be great – I press the lever ten times and I get my reward. I have control, I have agency!’ The dopamine is triggered by the anticipation, not by the reward itself. And if you block the dopamine release, you don’t get the lever-pressing. Because it’s not just about the anticipation, it’s about the motivation you must have to do the work needed to get that reward.

For those familiar with our U.S. Constitution, it’s not the ‘pursuit of happiness’, it’s the happiness you derive from the pursuit, and the motivation you derive from the pursuit. We’re a totally bizarre species in that a monkey can learn to lever-press, raise dopamine with the anticipation, and get a reward thirty seconds later. While we’re the species that can get a signal, and do the required work, and wait for a reward years from now. To get a good job because you studied hard in school, or to leave the planet better for your grandkids, to get a reward after you’re dead! We can sustain that anticipatory dopamine and work really really hard for rewards that are way off in the future.

Where this applies to gambling is if we take the scenario of doing the work and getting the reward, and we shift things a little. This was the work of a guy named Wolfram Schultz at Cambridge, who’s the pioneer in this field. We shift things so you get the signal, you do the work, and you get the reward – only 50% of the time. So what happens to the amount of dopamine you get when the signal comes on? Is it a little bit smaller than when there’s a 100% chance of a reward? No! What you see is that dopamine goes even higher, and 50% drives the system even more. You’ve now introduced a new word into the experiment – ‘maybe’. And ‘maybe’ fuels the system like you wouldn’t believe.”

50% is, in fact, the magic number here. At 40%, the dopamine is not as strong, because the person knows that they are more likely than not to be disappointed. At 60%, the same thing happens because the person knows they are more likely to get a reward than not. 50% creates the greatest uncertainty, and therefore the greatest dopamine rush. This is a psychological principle that has been central to casinos around the world. Blackjack players win about 49% of the time. Craps, 49.5%. Roulette, 48.6%. Not only do the almost-even odds enhance the anticipation of the players, this setup keeps them at the table playing longer and spending more money.

Gambling scandals are nothing new to sports. Boxing has been dealing with accusations of match-fixing since the beginning. There have been scandals in sumo wrestling, badminton, darts, and e-sports. But in North America, the biggest gambling scandals that stick in the public consciousness have been around baseball. The National League was established in 1876 to provide an alternative to the wildly corrupt match-fixing culture that permeated the sport at the time. Eight members of the 1919 White Sox conspired to throw the World Series at the behest of gamblers. Pete Rose was famously banned for life in 1989 because he bet on his own games. In the early 80s, Major League Baseball threatened two of the sport’s biggest icons, Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle, with permanent bans because they were working as greeters at a casino. Baseball spent more than a century fighting to preserve the public perception of integrity in the game, and any association with gambling undermined that credibility.

Then, in 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court declared a federal ban on sports gambling to be unconstitutional, and the floodgates opened overnight. Gambling could now expand outside Nevada, where it had been confined to Las Vegas for decades. Sports books, apps, and website sprang up almost immediately, and the money began pouring in. By 2021, the Canadian government had followed suit, legalizing single-game betting in our country.

It’s hard, one imagines, to say “no” to money. Especially when that money comes in really, really easily. Every major North American sports league has hopped into bed with gamblers with both feet. Even baseball, which for so long had fought to keep even the appearance of impropriety at bay, caved to the allure of the easy dollars. Why try to track down and make deals with sponsors and advertisers when gambling apps just deliver a dump truck full of money to you? It requires little effort to say ‘yes’, and your sport is now suddenly more lucrative than ever.

The sports leagues are raking in easy money. Athletes are raking in easy money. Connor McDavid and Wayne Gretzky are teaming up for Bet MGM ads. The Manning brothers are shilling for Caesar’s Sportsbook. Charles Barkley is endorsing FanDuel, LeBron James is endorsing DraftKings, and even college athletes like gymnast Livvy Dunne are appearing in ads for Fanatics Sportsbook.

It takes a huge amount of money to pay all the celebrity endorsers, to run ads from beginning to the end of every game, and to sponsor every halftime show, every intermission, and every pre- and post-game show we sports fans consume. That money comes from people. People who are gambling on sports, who are getting in over their heads, and who are increasingly seeing gambling as a normal, obvious part of the sports-watching experience.

Is it possible to put this cat back in the bag, to convince sports leagues swimming in easy money to go back to their now-antiquated business models? In just a few short years, the intertwining of professional sports and legalized gambling has made such a task gargantuan. Steve and Bruce think the place to start is with the advertising, and they are doing everything they can to stem the tide. Steve has hosted webinars, written op-eds and essays, and in 2025 he appeared before the Senate of Canada on behalf of the CPA. In his testimony, he said,

“Allowing any form of marketing of gambling runs completely against our members’ attempts to prevent and address mental health issues. It pushes all Canadians to consider betting, with an especially strong impact on our children and our marginalized communities. There is no need to market gambling. Would-be gamblers can easily find legal gambling on their phone apps, apps which can be policed. The Canadian government must not allow companies to push our population into addiction and, with all due respect, I ask all of you to help us help Canadians. As a country we can do better. We should and must ban the marketing of gambling.”

The Honorable Senator Marty Deacon was one of those who were receptive to Steve’s call to action. She says she doesn’t (yet) regret her vote in 2021 to legalize single-sport betting, but acknowledges that more care should have been taken at that time in regard to the advertising component of legalized gambling.

“Without the regulation of gambling, it was all happening in an underground, unregulated way, and taking in billions and billions of dollars. I don’t regret voting for the bill – yet – but the part that probably wasn’t given enough time and consideration was the media piece, the advertising piece. When the bill became law in the summer of 2021, a door opened quickly and strongly to advertise, and that was out of control. Part of our inundation of advertising is due to the way it was set up. Private sector companies were allowed to operate and compete against one another, which drove up the amount of advertising.”

Senator Deacon has recently introduced a bill to limit the advertising of sports gambling. What the bill says is that ads for gambling would be prohibited during the airing of the game itself. From puck drop to final whistle, from opening pitch to final out, there would be no gambling ads encouraging us to bet our money. (In fact, she is re-introducing this bill, which has moved through the Senate and the House before but has been stalled by elections and new governments. When a federal election chooses a new government – even if the incumbent party is victorious – all bills that have not yet become law die. They must then be re-introduced and go through the same procedure all over again.)

“I’m passionate about sport, and safe sport for all. What was amazing to me was the impact this was having globally on certain populations. For older people, just an annoyance with constant ads on the TV and pop-ups on their phones. But a combination of electronic communication, the pandemic, and traditional media, has left young people really exposed. And the ones who seem to be most impacted by addictive behaviour are younger males, around 14-34. All populations are vulnerable, but that’s a significant one.”

In just the past two years, the number of gambling scandals affecting the sports world in North America has skyrocketed. College sports have had to deal with a litany of incidents where players and coaches are found to be gambling. The NFL has suspended more than a dozen players and team employees. Golf, tennis, UFC, the NBA, and the NHL have all had issues of their own. And in baseball, the scandals are piling up in a major way. Shohei Ohtani’s translator stole more than $16 million to fund a gambling habit. Other players have received lifetime bans and even umpires have been disciplined for gambling. It’s a sport that lends itself remarkably well to today’s gambling landscape. When you can bet on the first pitch to the second batter in the fifth inning being high and outside, then what seems like a meaningless one-off play in the game can be an alluring prospect for that pitcher.

When the lines that hitherto defined the integrity of a sport become blurred, it sends incredibly mixed messages to the players involved in that sport. Players who, in many cases, are young enough that they do not yet have fully developed frontal cortexes either. You can give an interview on the DraftKings pregame show, you can accept a boatload of cash to endorse FanDuel, but you’d better not actually gamble! THAT’s unethical!

When the lines get blurred for athletes, they must also get really blurry for fans. Where once you might have rooted for the Ottawa RedBlacks on TV 18 times per year, and maybe attended a couple of games, now that doesn’t feel like being a committed fan. If you’re truly committed to the RedBlacks, you’ll bet on them to win, to cover the spread, and for Adarius Pickett to break up two passes in the third quarter. It’s just what people who watch sports do, isn’t it? Dr. Sapolsky says the ability to make these in-game decisions is particularly difficult to manage, because it doesn’t give the frontal cortex time to catch up.

“When you’re sitting in your Vegas hotel room late at night and thinking ‘oh my god, there goes half the kids’ college money’, it gives you some time to think about it, and some time for the frontal cortex to get things under control. By contrast, when it’s a fast decision, it is hopeless that the frontal cortex is going to get there in time. It’s the impulsiveness of violence, or the impulsiveness of pressing a button on your phone.

When I was a kid in New York City, they legalized what they called ‘off-track betting’, where you no longer had to go to the racetrack itself to place a bet. They had these nice shiny locations with friendly high school kids behind the counter taking your money, and it was all straightforward. And best of all, the money the state was getting from off-track betting was being spent on education. Great news right, it’s being used for something beneficial! What gets lost in that is that the money you are taking from people who are gambling away their savings is disproportionately from poor people. It’s redistributing the wealth in the worst possible directions. Here in the United States, a lot of that is because people without money are psychologically manipulated into thinking ‘I’m actually a rich person who just hasn’t gotten rich yet’.”

A gambling addiction is a little bit different than other addictions, in that the effects of it can be much more devastating. Once a person realizes they need help for a dependence on cocaine, or alcohol, they can take the steps they need to get better. Although it can be very difficult, with the support of family and friends they can turn things around and recover. With gambling, the same is true – but even after recovery there is something hanging over their head. An enormous and often life-altering amount of debt. It’s no wonder that suicide prevention websites have sections dedicated entirely to gambling.

So what can we do? Most people – including many mental health professionals – think that an outright ban on gambling is a non-starter at this point, and that even attempts to ban advertising for it will face stiff opposition. The proposed solutions nibble around the edges, and could make a difference, but they are unlikely to do anything major to stem the tide. Steve has a few suggestions, including adding a feature to gambling apps where every time you log in you get to see a running count of how much money you have won or lost. It might make us pause for a moment when we open our app and see that we’ve lost $12,000 in nine months. That pause might give our frontal cortex enough time, and enough data, to make us reconsider going back in to place another bet and lose more money. He also makes a point about the way we advertise (or don’t) other products.

“We have legal THC in Canada, you can go buy cannabis anywhere you want, but it is not advertised. Remember the Steppenwolf song The Pusher from the 60s? It makes the distinction between someone who goes out and finds a dealer, versus someone who isn’t looking but the dealer finds them and pushes their product. A ban on advertising for THC says ‘it’s a free country, you can do what you want to do, but there’s a reason to worry here so we’re not going to encourage this behaviour’.”

Dr. Sapolsky says that while the intention makes sense, an outright ban on gambling itself could end up backfiring, particularly among young people.

“I can see [making it illegal to gamble] backfiring, with the allure of the illicit. I’m not sure it would work on young people, because the ban could make them feel like teenage desperados, you know. Cigarette companies have figured this out, introducing vapes in bright colours and with exotic flavours. It combines the appeal of the illicit with the attention-grabbing novelty of the product, and even though vapes aren’t advertised, the industry is incredibly lucrative and really skilled at taking money from teenagers.”

Senator Deacon says we’re going to get there one step at a time.

“To move this through the Senate and the House, based on what we’ve learned with alcohol and tobacco, I felt that a full ban [on advertising] would have really slowed down the intent of the legislation. My bill is a moderate way to get the ball rolling, and the House can take over the bill and do a full ban if that’s what they like. Some of the things we could be looking at are ‘ten before and ten after the whistle’ (so no ads during the game itself). Denmark is doing this, and gambling companies there can advertise only between 1 am or 5 am. Also, anyone doing the advertising, or appearing in the ads, must be over 25 and can’t be an athlete.”

She also says that while letters and emails to MPs do work, emails and letters to senators do as well. For people who care about this issue and are passionate about it, contacting your elected officials, and unelected officials, goes a long way and could move legislation along to the point of a full ban.

“Now the bill is sitting in the House, and it has been presented there. We want families, organizations, and Canadians to reach out to their MPs. Bruce’s Ban Ads For Gambling group is very effective in doing this, and it makes more of an impact coming from him and from Steve than it does coming from me.”

Bruce, and Steve, and their colleagues from all over are going to continue this work as long as they can. As Dr. Sapolsky said, we human beings are unique in that we can put in the work today for a reward that may not come for a long time. To join the campaign, visit Bruce’s website and click ‘get involved’ for a form to send a letter to your MP. Be vocal about your opposition to sports gambling ads. And if you’re on one of those apps, take a moment to look back over your results and take stock. Maybe determine whether it’s a good idea to continue placing those bets. Your frontal cortex will thank you.

Just about every little kid has accidents from time to time. But more than one poop accident in a month (encopresis) or more than two pee accidents per week (enuresis) might be cause for concern. Dr. Jen Theule helps explain what signs to look for, how best to potty-train kids, and how psychologists help resolve problems that might occur as children get a little bit older.

How do we gather information to store it in our memories? How do we retrieve that information when we need it? And can you actually forget how to ride a bike? Dr. Elena Antoniadis, psychology professor at Red Deer Polytechnic and an adjunct professor at the University of Calgary, joins us for a look at how we form memories, how we can enhance our recollection abilities, and more.

Zaineb Bouhlal, the CPA’s Membership Database and Services Administrator, says she has forgotten how to ride a bike. Is such a thing possible? After all, it’s the most-clichéd thing we’re all supposed to remember as long as we live. “Like riding a bike” is the phrase used to describe most everything we store in our procedural memory. Biking, swimming, typing, driving a car, any skill that involves sensory-motor coordination that we’ve practiced and acquired is one we can re-gain if we’re put back into that same setting.

Dr. Elena Antoniadis is a psychology professor at Red Deer Polytechnic and an adjunct professor at the University of Calgary. She says,

“Once you’ve learned to drive a car it would be very difficult to forget how to carry out all the operations that go into driving a car. But it’s not a memory that our conscious or declarative systems have access to. So, for example, we can’t tell a younger sibling how to ride a bike – it’s not something we can write a manual for. It’s something that the body registers, and then the implicit memory system builds the memory of that skill.”

There are memories that are encoded explicitly – like facts, knowledge, the things you learn in school. You are making a conscious decision to remember those things, and what makes a memory “explicit” is that we can consciously access it and describe its contents, rather than simply showing it through behaviour. Then there are memories that are encoded implicitly – this is how we build habits, conditioned reflexes, and learned responses. The brain registers patterns without us being aware of them. The basal ganglia in the brain helps us build the skills, the habits, and the automatic responses that come from the implicit encoding of memories. Language is often one of those areas that we learn implicitly from a young age.

Before I worked at the CPA, I worked at The Dementia Society of Ottawa & Renfrew County (DSORC). DSORC runs programs for people living with dementia, programs which often make use of deeply encoded memories to recall songs from childhood, or to move and exercise in familiar ways. When I was there we had an Arabic-language program, for people who had grown up in the Middle East but now lived in the Ottawa area. One older man came to that program with his family. They had come to Canada from Saudi Arabia a decade prior, and now their father was living with dementia. Unfortunately, the program wasn’t working very well for him because, although he had spoken Arabic with his family for his entire life, he no longer spoke the language. Instead, he was speaking a language they had never heard before. After a while, the Dementia Care Coaches determined that he was speaking Farsi. He had grown up in Iran, but had never told anyone in his family about his childhood in another country. Now that he was losing his short-term memory, and his longer-term memory was starting to fragment, he was left only with those memories that had been deeply and implicitly encoded in him some 75 years ago.

By contrast, memories that have been explicitly encoded behave differently. We use different methods to retrieve them, and our methods change over time as we experience more of the world from a personal perspective. Says Dr. Antoniadis,

“Children are more emotionally attuned to those around them, their environment, and their primary caregivers. They rely more on the emotional parts of the experience to build their memories. As we age we can rely more on our own lived experiences, the episodes that take place in our lives. I witness this in my own classes. I see mature students who are returning to school, and they can connect something factual with something they’ve experienced in the workplace or in a familial environment. Because they have a broader repertoire of meaningful experiences they can connect with the information they’re receiving.”

That increase in experiences can be a little bit of a double-edged sword when it comes to memory. Think of major events that happened in your life, and the way you remember them now. For me, a good example is 9/11. I know I was in radio school, and that I was with Vicky McKenzie. But when I discuss that moment with Vicky today, we have very different recollections of how we responded, who was around, and what we did next. Either one of us is right and the other wrong or, more likely, we’re both a little bit wrong.

A major event like that one feels like it happens in an instant, and that we have a snapshot in our minds that will be accurate forever. But it doesn’t really happen in an instant. After the event, there is news coverage of it. Your family is going to be talking about it, your co-workers or fellow students or schoolyard friends will also be talking about it. Now, within a few months of the event, you have added untold amounts of information to that first memory, which can distort your recollection of the specific facts.

I am almost certain that we watched, in real time, the second plane hit the World Trade Centre. Vicky says we started watching only after that happened. I remember going, later that afternoon, to donate blood with Jamie Johnston. Partly because we didn’t really know what else to do, and partly to put on our journalist hats to talk to people who were also doing the only thing they could think of in that moment. Jamie tells me we actually did that several days later. Dr. Antoniadis says this is quite common.

“Many times we have factual information about an occurrence. That information comes in separate from the memory itself, but becomes integrated into the memory. This is the reason why sometimes police officers who arrive at an accident or something like that will separate witnesses to make sure their stories don’t impact the other person’s recollection. Hearing another witness describe what they saw can become integrated into our own memory of the event, even one that happened moments earlier.”

In 1994, Chuck Knoblauch of the Minnesota Twins finished the major league baseball season with 45 doubles. That season was shortened by a strike that resulted in no World Series being played, much to the chagrin of Expos fans who thought they had a great chance at their first title, and Blue Jays fans who were denied a chance at a three-peat. Had the season lasted a full 162 games, Knoblauch was on pace to hit 65 doubles and threaten the all-time record of 67 set by Earl Webb in 1931 with the Red Sox.

This is a fact I know. It’s one that has stuck in my brain since my youth, and while there’s no good reason for me to remember, I have never forgotten what might have been in 1994. I find it somewhat interesting. My wife finds it somewhat irritating. “You can remember how many doubles Chuck Knoblauch hit in 1994, but can’t remember that you were supposed to take the garbage out?” she’ll say. And I will respond with “I dunno – that’s just how my brain works, I guess”.

It turns out though, that this is how all of our brains work! Our capacity for short-term memory is finite, but our long-term memory retention is – as far as we know – limitless. Dr. Antoniadis explains more.

“Short-term memory has limited space, but long-term memory is limitless in its storage capacity. We have variety in the mental operations we perform – encoding, storage, and retrieval. But we also have variety in the types of information that we create. Long-term memory is, according to the scientific literature, limitless. We can continuously keep learning and acquiring new information.”

Dr. Antoniadis says that because our short-term memory has a finite capacity, there can be a bottleneck where we are subconsciously deciding whether to commit information to more long-term retention, and deciding what ideas we might discard. I likely won’t need to remember, ten years from now, that I took out the garbage today or shoveled the driveway. It won’t come up in pub trivia. But Shohei Ohtani’s 3-homer 10-strikeout playoff game…that might come up! It’s going in the vault.

So, I’ll remember that for pub trivia purposes, and it may or may not come in handy a decade from now. But what of the people who excel at that kind of memory retrieval? The people like Ken Jennings, Mattea Roach, or Amy Schneider who can get on Jeopardy! and just crush it?

“Retrieval depends heavily on cues and context. Individuals who are practicing retrieval and recollection of accurate information may be using retrieval cues that will help them enhance that. Can they use something about where they were at the time they learned it? What they were doing when it happened? They’re focused on matching the cues that were present when that information was presented. This happens in school too – if you’re writing an exam in the classroom where you learned the information, you’re more likely to be able to retrieve that information than you would be if you wrote it in a different classroom.”

So…does that mean that the old adage is true? The one that says if you study under the influence of weed or alcohol you should write the exam in the same state so you can maintain the same frame of mind and to increase the likelihood that certain cues will assist you in retrieving the information you need? Dr. Antoniadis says yes.

“The concept is supported research findings. It’s called ‘state-dependent memory’. When we’re in a certain state – an emotional state for instance – we’re more likely to retrieve memories from that state. When we’re happy, we retrieve joyous memories. When we’re sad, we’re more likely to recollect sad memories. When our physiological or emotional state matches experiences we’ve had with a similar state, we’re more likely to retrieve the memories from that time.”

We hear a lot about scent and memory in popular culture. Perhaps more than any of our other senses, smell triggers memory cues in subtle ways that make it easier for us to recall old events or retrieve information buried deeply in our minds. Dr. Antoniadis says this is because our olfactory sense (smell) is very much connected with the parts of the brain that houses the instinctual parts of our memories.

“Instead of it being something we are consciously aware of, or something we can explain or articulate, it’s a non-declarative memory. That means it’s something we feel, something we can enact or show through our behaviour, without being able to explain it. We might have an emotional reaction to a frightening cue without being able to explain why we responded that way. Other times, emotional reactions can be the impetus to conjure up the conscious memory if it’s there. It can be a gateway to a conscious recollection of a specific memory.”

A lot of memory exists in a place beyond our specific awareness. When we say we can’t remember something, that doesn’t necessarily mean we haven’t stored the memory, but that we’re having trouble retrieving it. Like thinking we have forgotten how to ride a bike, when in fact we might well remember exactly how to do so when we’re put in a situation that is reminiscent of the time when we did ride a bicycle all the time.

At the CPA, we are going to put this to the test. It will be an anecdotal study, and the data will be applicable only to Zaineb. Once the snow has melted, in late May or early June, and Stewart starts riding his very expensive bike in to work again, we are going to perform an experiment in our parking lot to see if Zaineb can, in fact, summon the bike-riding knowledge she once had when put in that situation. It will be one more experience that we can all add to our repertoire of experiences that allow us to draw on our memories.

Stewart’s bike is very nice, and he takes tremendous care of it. We will wait until the day we conduct the experiment to tell him that his bicycle has been volunteered. So don’t tell him before then.

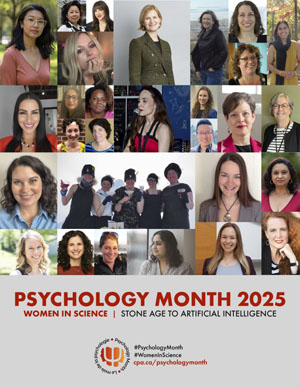

Women in Science

The theme of Psychology Month for 2025 is women in science. This month we will be highlighting the work of 34 remarkable scientists, including eight brand-new podcasts and profiles. Psychology Month 2025 will follow scientists from students to retirees, and take us from BC to PEI, and from the North Pole to outer space.

Liisa Galea

Dr. Liisa Galea is a scientific lead for the CAMH (the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health) program womenmind™. It’s a community of philanthropists, thought leaders and scientists dedicated to tackling gender disparities in science, and to put the unique needs and experiences of women at the forefront of mental health research.

Womenmind™ Liisa Galea

“You know how to *take* the reservation, you just don't know how to *hold* the reservation. And that's really the most important part of the reservation: the *holding*.”

- Seinfeld, ‘The Alternate Side’, 1991

The National Institute of Health (NIH) in the US introduced a policy* in 1993 where applications for research that plans to involve human subjects for clinical trials must address the inclusion of women, minorities, and children in the proposed research. As a result, the scientists applying for research grants did exactly that. They included women, minorities, and children in their studies. But to what end?

It’s easy to include women, minorities, gender diverse people, but if you don’t look to see if it’s affecting outcomes for those individuals differently, then you’re doing only half of the work – and missing the part that makes inclusion important. But precious little research, since the introduction of that policy, has made that distinction.

*It should be noted that it is quite difficult, at the moment, to ascertain exactly when the NIH instituted that policy, or what the outcomes have been, since the new American presidential administration has scrubbed their websites and resources of any language involving “minorities”, “disparity”, “bias”, and even “women”.

Dr. Liisa Galea leads the Women’s Health Research Cluster at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) in Toronto. She is the principal editor of Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, the Past President of the Organization for the Study of Sex Differences and co-Vice-President of the Canadian Organization for Gender and Sex Research. She is also the scientific lead for the CAMH initiative womenmind™ and a Seinfeld fan.

“I grew up in a time when I had to wear a skirt in school because I was a girl. I’m so grateful to my parents for saying I was smart and could do anything I wanted to do…except perhaps become Pope! I was told I was different because I was a girl, but it didn’t upset me – it just made me curious as to why people thought that. When I started university, I got really interested in the area of female brains vs male brains and I wanted to know all about the differences and what that might mean for our health.”

womenmind™ is a community of philanthropists, thought leaders and scientists dedicated to tackling gender disparities in science, and to put the unique needs and experiences of women at the forefront of mental health research. Dr. Galea and Dr. Daisy Singla, a clinical psychologist who specializes in perinatal mental health, are womenmind™ scientists who do a lot of this important work.

The gender disparities in healthcare are real, and they are significant – particularly in the area of mental health. Diagnoses of mental health issues can take up to two years longer for women compared to men. There is a sense in the public sphere that men don’t talk about their feelings as much as women do, and are less likely to seek help with psychological issues. Despite this, just looking at mental health disorders, there is still a delay in diagnosis of more than two years for women. That delay can interfere with treatment plans – if you’re being misdiagnosed or dismissed with your symptoms you’re not getting the treatment you need, and we all know that earlier interventions lead to better outcomes.

A study done by the World Economic Forum showed that globally, women spend 25% more of their lives in poor health than men do. Dr. Galea thinks this is partly due to health science being historically dominated by men studying males.

“In terms of mental health specifically, there are many reasons for the delays in diagnosis, but one of the major reasons I think is because most of our medical knowledge – including the symptoms on checklists for diagnoses – are based on the experiences of men. So much so, that we often call symptoms for mental health disorders in females ‘atypical’. We use ‘atypical’ a lot in the context of neurodiversity – autism, ADHD, and so on. And there are more males diagnosed with those conditions. We see more females than males diagnosed with depression, but we also see that ‘atypical’ label applied to depression in women. If there are twice as many women diagnosed with depression as men, how are their symptoms ‘atypical’? I think it’s because our scales were developed a long time ago, thinking about findings in males and the experiences of men.”

As a result, healthcare providers don’t acquire enough knowledge about sex and gender disparities in disease presentation and symptoms. This has real consequences for women in the healthcare system, but also for funding bodies. As a researcher that’s been in this field for 28 years, Dr. Galea gets a lot of comments from editors and funding agencies that *this [female-centric subject]* isn’t a really important thing to study because it’s “only in a subset of the population”.

Dr. Galea and her team did a review, looking only at male/female studies in neuroscience and psychiatry. 68% of studies were using both male and female participants, but only 5% of those studies looked to see whether sex made a difference. As Dr. Galea says, “you can have 2 females and 8 males in your control group, but the reverse in the treatment group, and you can’t do the analysis properly because you don’t really have the sample size to see if it made a difference.”

27% of the studies were focused solely on males, and 3% solely on females. Dr. Galea’s team then looked at Canadian grants, which resulted in similar percentages. In 2023, mental health specifically for women made up less than 1% of the funding of the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR), the major federal agency responsible for funding health and medical research in Canada.

Funding for research is, sadly, a hot-button issue at the moment as the new American government tries to shut down funding at the NIH for everything they deem to be “woke”. This has impacted many of Dr. Galea’s colleagues and the work they do, especially since the cuts seem to have been attempted in the most damaging and misguided way possible. The new administration looked for the key words they didn’t like, and cut funding for everything that contained words like “bias” or “diversity” or “environmental”. They also targeted words like “trans”, “non-binary”, “female”, and “woman”.

This could result in the ending of studies into things like the gut microbiome, where one of the measures is alpha-diversity and beta-diversity – referring to the variety of bacteria that live in one’s gut. Electricity studies using vacuum tubes which require a current called “bias”. And studies involving women’s health. Dr. Galea says this is even more dangerous than it seems, because stopping the study of women’s health affects men as well. She gives an example,

“Lazaroids were a drug that was discovered for stroke recovery. It worked miracles for people who had suffered strokes. It was discovered pre-clinically first, where it worked on mice and rats, and then it went to double-blind randomized control clinical trials, our gold standard. It turns out most of the pre-clinical work was done in males. The early clinical trial was done all in men as well, since men are more likely to suffer a stroke earlier in life (but this switches to more women later on in life). It failed phase 3 clinical trials, which included women, and the drug is not on the market. It put the drug company out of business. But when people did secondary analyses, it turns out lazaroids work wonders in men – but not in women. In fact, in women it might have made things worse. But that’s a drug that’s now not on the market that might do wonders for men’s health! Isn’t it in our collective interest to find out what drugs work better in different populations?”

This upheaval could have devastating consequences for the future of women’s health, an area that has critical problems already. Consider menopause. This is something that will happen to 50% of the population. And yet, 0.5 % of all studies in neuroscience, and in the field of brain health in general, are on menopause. Physicians get about 1-3 hours of training on menopause and its effects on health.

When women go through menopause and have significant problems, they get sent to specialists – gynecologists. But – only 30% of American gynecological programs had anything about menopause in them. So well above half the time women get sent to see specialists for this, they’re going to see someone who hasn’t been trained in it, and may have learned very little about it. Says Dr. Galea,

“We have to become our own specialists, but we need informed research to know what we can do to offset our symptoms. Laura Gravelsin (one of my postdocs) and I just had a paper accepted called ‘One Size Does Not Fit All: Type of Menopause and Hormone Therapy Differentially Influence Brain Health’, because there are many hormone therapies and many menopauses, and we have to determine which one works for us individually.”

Not all scientists who study women’s issues are women, and not all women specialize in those issues. But having more girls going into scientific disciplines, and being supported along the way, can’t hurt. This is another of womenmind™’s goals. Dr. Galea points to the fact that there are more female psychologists, and physicians, than there are male. And yet, at the dean level, or director or supervisor level, the proportion of women steadily decreases the higher in rank you go, compared to men. She says,

“Girls are very interested in all scientific fields at a very early age, but as time goes on and we get further and further in our career, the disparity starts to grow. At the university level, you see more women and girls in the sciences, but the gap gets a little wider the further up you go, at the graduate level and then at the assistant professor level.”

With this in mind, womenmind™ has a robust mentorship program for all female and gender-diverse scientists that has seen remarkable results. About 60% of the female and gender-diverse scientists at CAMH have gone through the mentorship program, and there is a staggering 100% approval rate – every single person coming out of the mentorship program has said they would recommend it and they want it to continue.

And continue they will, with the passion and determination of the new scientists and the veterans like Dr. Galea. In addition to womenmind™, she runs her own lab investigating how hormones (mostly estrogens) influence the brain. They focus on stress-related psychiatric disorders like depression, and also Alzheimer's. Dr. Galea also runs the Women’s Health Research Cluster which in the realm of knowledge translation, and seems like a lot of fun! They just had an event in Toronto called ‘Galentine’s Day: Love your Brain’ which was about girls and women and anyone who identified as such loving their brains through hormonal changes like puberty and menopause.

The experiences of women and girls going through hormonal changes are varied and diverse. The path through adolescence, or menopause, is rarely a straight line. Nothing in life is a straight line! Even Dr. Galea’s journey to doing the work she does today (and Parks and Rec fandom) took numerous twists and turns. She says,

“I started in engineering first, and took Psychology 101 with Susan Lederman. She works in perception. She said ‘I’m the first Canadian, the first woman, and the first psychologist to be asked on a NASA panel’. She was there because astronauts were complaining they couldn’t feel anything through their gloves when they were out on a spacewalk. I was hooked. I thought, ‘that’s so interesting, I want to learn that’. It’s not at all what I ended up doing, but I took a lot more psychology as a result. I ended up studying women’s brains, and I’m always going to do it!”

Someone’s got to do it. And someone else entirely has to support them by making it a priority to ensure they continue to get to do it. With initiatives like womenmind™, the Women’s Health Research Cluster, and the research being done by Dr. Galea and her colleagues, the future of gender-inclusive health science looks promising. But if we want to make the most of that promise, the scientific community and policymakers must make it a priority to ensure this research continues.

Madeline Springle is a second-year Ph.D. student at the University of Calgary, who is winning awards for her ability to mobilize knowledge. Specifically, she is taking the research she has done into one-way video interviews, and using it to help people who might use this knowledge to better prepare for their own job search.

As we close out Psychology Month, we wanted to highlight knowledge translation (explaining the science for a more general audience) and knowledge mobilization (putting new findings into practice such that they help those they were designed to help) because without those, science exists in a vacuum!

Cette semaine, dans le cadre du Mois de la psychologie dont le thème, cette année, est « Les femmes et la science », nous présentons Sophie Bergeron, Ph. D., qui détient une Chaire de recherche du Canada sur les relations intimes et le bien-être sexuel au Département de psychologie de l’Université de Montréal, où elle dirige également le Centre de recherche interdisciplinaire sur les problèmes conjugaux et les agressions sexuelles (CRIPCAS), l’Équipe SCOUP Sexualité et Couple, et le Laboratoire d’étude de la santé sexuelle. Ses travaux portent sur les déterminants psychosociaux de la santé sexuelle des individus et des couples ainsi que sur le traitement des dysfonctions sexuelles.

There has always been a stereotype that women are “more emotional” than men, and even that they are “too emotional” for leadership roles. Dr. Winny Shen joins Mind Full to discuss the results of her study which suggest that not only is that stereotype untrue, the exact opposite might actually be the case.

Jessica Strong

We all plan to get older. So why do so few of us gravitate toward working with older adults? Dr. Jessica Strong is a Geropsychologist in the department of psychology at the University of PEI. She tells us about cognitive reserve, fights against ageism, and discusses how a passion for music led her toward her current career path.

“You see the hood's been good to me, ever since I was a lowercase g. But now I’m a Big G.”

- Montell Jordan

In his monster 1995 hit ‘This Is How We Do It’, Montell Jordan makes the distinction between a “lowercase g” and a “Big G”. In his case, he’s making reference to being a young child, understanding and evincing the gangsta part before he grew to adulthood and achieved proper, professional gangsta status by releasing a staggeringly popular debut single.

Like Montell Jordan, it was music that led Dr. Jessica Strong to her eventual career path, one where she too makes a distinction between lowercase gs and Big Gs. ‘Big Gs’ are the expert specialties, Geriatrics, Gerontology, Geropsychologists like Dr. Strong. ‘Lowercase g’ refers to the little competencies everyone needs to have. Social workers, family doctors, personal support workers at retirement residences, caregivers, or retail workers. Anyone who deals with an older population in their day-to-day lives. Says Dr. Strong,

“I have a lot of students who aren’t necessarily interested in Geropsychology (big G), but we work on developing this ‘lowercase g’ workforce, which is not working with older adults exclusively. They may be a generalist psychologist, but one who has the competency to work with older adults. They understand the cohort issues and generational differences, and know how to modify an intervention or screen for mild cognitive impairment.

I tell all our clinical students ‘you want to work in paediatrics, great! How many grandparents are raising children these days? For your paediatric client, if you’re noticing something off with their grandparent, you’re going to want to figure out whether this is anxiety and stress because they’re raising a nine-year-old, or could this be a mild cognitive impairment? And how am I going to figure that out in a way that serves the interests of my paediatric patient?’”

Dr. Strong is an assistant professor in the department of psychology at UPEI, and a registered clinical psychologist who specializes in Geropsychology. Geropsychology is a subsection of gerontology – the broad study of aging, lifespan, development and identity in late life. It’s a discipline that focuses on relationships, mental health, cognition and more generally the psychology of aging.

It was music that led her toward this career path, as she started playing piano at the age of 9 and soon picked up more instruments, playing alto sax in the high school marching band. It was in high school that she started thinking about music therapy as a career. But music therapy is a pretty specialized occupation, and Jessica is someone who likes to keep as many options open as possible.

In her final year of high school, right around the time we were all learning that “southcentral does it like nobody does”, she shadowed the music therapy program at her local university. She quickly realized that there was a way to get into this while keeping more doors open, and she ended up doing two simultaneous undergraduate degrees – one in music performance, and one in psychology. The idea was that from there she could get a Master’s in music therapy if she chose that path.

But psychology research really spoke to Jessica, who started to become far more interested in the mechanisms of why music makes a difference for people, rather than just using it as a tool. She had done a little bit of work with older adults at an occupational therapy lab at Washington University in St. Louis. Then she moved to Germany, where she worked at a mental health institute for older adults, the Central Institute for Mental Health in Mannheim. She had become a lowercase g.

Soon, she realized that what she really wanted to do was work with older adults. She had never heard the term “Geropsychology” before, but she lucked into a program at the University of Louisville in Kentucky, and was accepted into their Clinical Psychology program, working under the mentorship and supervision of two Geropsychologists. She earned her Ph.D., became a Big G, and says she has never looked back.

“One of the most rewarding things about working with older adults is that they are some of the more complex human beings in the world. They’re such a heterogeneous population because they have all of the demographic differences that any of the rest of us have – gender and race and so on – but they also have all their lived experiences and the changes that have come with those. Physiological aging, emotional aging, cognitive aging. It’s really intellectually stimulating and exciting for me because they’re so much more complex than any of the other groups I’ve worked with who haven’t done as many things.”

Soon, Dr. Strong was working in Boston at a rehab facility in the Veteran’s Health Administration. She studied how integrating music into a mental health group could destigmatize talking about mental health for older male veterans. They got some great feedback, the veterans felt like this group was different from others they’d been in before, and that the use of music made it easier for them to talk about things that both as men and as veterans they’d been conditioned to avoid. Music gave them a way to feel it without necessarily having to find the words.

One of the sessions Dr. Strong did with this group used “a bit of a music therapy technique”. They would start the group session by reading the lyrics to a song aloud, like a poem. They’d talk about the imagery, and what they thought the artist was trying to convey. Then they would listen to the song to see if it felt different than just reading through it. Did the addition of music take away from the message, or did it add something? The veterans in the group, men whose gender and military service compounded a reticence to speak vulnerably, went to deep places dissecting the music.

Dr. Strong says ‘What A Wonderful World’ was a group favourite. Given the age of the participants (some Vietnam veterans, others Korean War veterans, and some survivors of World War II) it makes sense that a song from the 60s resonated as much as it did. Music is often associated with memory and nostalgia, most particularly the music we heard around major life events in our adolescence and in early adulthood. Like a wedding song, a graduation song, or one you heard while you were heading off to war.

When similar sessions are held forty years from now, there’s a good chance a psychologist like Dr. Strong will be integrating much different music into this kind of group therapy. They will discuss what Mr. Jordan is trying to convey when he suggests we “flip the track, bring the old school back”. Dementia support groups that connect people through sing-a-long music will sound like one of those Pitch Perfect mashups. “I reach for my 40 and I turn it up / designated driver take the keys to my truck”.

Music not only triggers memories, it shapes our brains as we age. Dr. Strong is specifically interested in the brains of musicians, and the effect a lifetime of playing music has on the aging process. She talks about something called Cognitive Reserve. This is the idea that everything we do in our lives builds up a reserve in our brains. Dr. Strong describes it like a battery you can charge. Having a formal education, speaking a second or third language, having strong social connections, these are factors that charge our battery and make us more resilient against cognitive impairment later in life.

“If someone has a really high cognitive reserve, a scan of their brain might look awful, with disease, or vascular damage. But they might still function okay because they’ve built up this reserve over time that allows their brain to circumnavigate those damaged pathways. Someone with a lower cognitive reserve might have a brain that looks relatively okay on a brain scan, but they might be showing signs of mild or moderate dementia in their functioning.”