Pandemics are complex dynamic systems that shift and change over time due to the influence of a huge and interacting set of variables. Cultural contexts, although they tend to change more slowly, are similarly complex. Research on cultural processes unfolding under pandemic conditions is therefore fraught with uncertainty. Nonetheless, thanks to research conducted during and after previous disease outbreaks combined with the first studies rapidly assembled in the first months of the current pandemic, we are in a position to make some initial evidence-based claims as cultural and cross-cultural psychologists.

Contemporary cultural / cross-cultural psychology rejects the idea that biology and culture are opposed. The SARS-CoV-2 virus is straightforwardly biological, as is the associated disease, COVID-19. Nonetheless, the cultural context shapes the ways in which people engage with this threat, affecting everything from pre-existing health status (and hence, vulnerability) and living conditions to how people react to the threat of the virus and to the measures being taken to combat it.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we have already observed cultural variations in:

- Pre-virus readiness for pandemics and other disasters

- Transmission rates

- Behavioural responses (e.g., mask-wearing, handwashing)

- Official policies (e.g., “social distancing”)

- Compliance with official policies

While our biological immune system is critical when we are infected with a virus, our behavioural immune system helps protect us from getting infected in the first place. It does so by helping us to detect pathogen cues and then to trigger relevant emotional and behavioural responses to these cues. Many aspects of this system are shaped by the local cultural context.

Indeed, some aspects of culture itself may have been shaped by variations in historical levels of infectious disease risk, leading to longstanding differences between cultural groups. For example, cultural groups with a high historical prevalence of pathogens tend to show lower levels of social gregariousness and greater concern about outgroup members.

We can understand the links between cultural context and COVID-19 at three levels: 1) macro-level of whole societies; 2) meso-level of families and communities; and 3) micro-level of individual people.

Macro-level of Whole Societies

Societies differ in numerous demographic ways relevant to COVID-19. For example, societies differ in terms of the strength of the economy, development of the healthcare system, urban population density, and degree of emergency preparedness.

These structural differences are shaped by longstanding cultural tendencies. For example, we would expect societies characterized by widespread valuation of a long-term time horizon to emphasize preparedness as compared with societies focused more on short-term concerns.

Political polarization can also lower trust, leading people to prefer advice from politically motivated sources and/or advice that fits with political preconceptions. Structural discrimination against certain ethnocultural groups can also compromise trust. There is an added concern that such polarization can lead different segments of society to act in conflict with each other rather than in pursuit of common goals.

Societies also differ in cultural patterns of values and behaviour. The extent to which people in a given society move between different locations, or geographical mobility, is associated with a set of skills that facilitate frequent shifts between different social networks, or relational mobility. Recent research has shown that the transmission rate during the 30 days after the first case of COVID-19 is correlated with societal levels of relational mobility. It appears that one problem with mobile societies is increased ease of transmission across geographical and social distances.

The extent to which people in a given society adhere closely to rules or look for opportunities to violate such rules can be understood as a distinction between tightness and looseness. Tighter societies are more likely to accept behavioural constraints. Particular advantages may accrue to societies able to maintain tight-loose ambidexterity: tight norms with sufficient looseness to promote ‘outside-the-box thinking’. This combination of self-restraint and creativity might be very helpful in pandemic situations, as both are needed.

Meso-Level of Families and Communities

Normative behavioural patterns in particular social networks can affect the transmission both of (a) an infectious disease and (b) ideas about the disease. Whereas the former requires study of how a virus propagates within and between bodies (e.g., increased contagion of a virus that survives for a long time on surfaces), the latter requires study of how ideas propagate within and between minds (e.g., increased believability of an idea frequently repeated by a source deemed credible).

Social networks accelerate transmission of harmful and helpful ideas about a given disease and what one ought to do about it. Such transmission can take place through conversation or observational learning, but also through traditional news sources or social media. Social capital, or the value that comes from our social networks and connections, varies across families and communities. Whereas a focus on strengthening intra-group connections (high bonding capital) would keep the virus in the local bubble, a focus on strengthening inter-group connections (high bridging capital) would allow the virus to be transmitted more widely.

The centrality of social connectedness in many communities is reflected through participation in communal events, which may feel obligatory (e.g., festivals, weddings, funerals). Emotional expressivity in certain communities may be associated with close talking, handshakes, kissing, loud exclamations, and so on. All of this is conducive to droplet projection, which further propagates the virus.

Measures taken to combat pandemic spread are also received differently depending on local characteristics. For example, families and communities differ in their acceptance of hierarchy—and hence, compliance with authority. One complicating question is who is a legitimate source of authority: do people look to public health officials, family members, religious leaders, or celebrities? Moreover, public health officials may require measures that directly contradict local imperatives; impeding appropriate burial of the dead, for example, can be emotionally charged.

Given that outbreaks of disease are associated with high levels of anxiety and uncertainty, the potential for increased intergroup tensions should not be underestimated. There is evidence that disease risk increases prejudice and discrimination against:

- Outgroups that are disfavoured in general (e.g., visible minorities, Indigenous people, the poor and especially the homeless);

- Outgroups that are specifically associated with the source of transmission of a given disease (e.g., East Asian Canadians, in the case of COVID-19);

- Outgroup and even ingroup members that by vocation or circumstance have a higher degree of exposure to the disease (e.g., grocery store workers, healthcare workers—although in the latter case, there are also positive views).

Stigma has consequences, including stress/distress, barriers to effective healthcare, mistrust, distortion of public risk perceptions, hate speech/crimes, and other forms of marginalization. These consequences can further disease spread (e.g., stress weakens the immune system while healthcare barriers delay treatment).

Disfavoured groups, moreover, are at additional risk due to social inequalities. For example, certain minority groups are more likely to be found in jobs that involve high contact but low compensation. Disfavored groups can show ‘cultural mistrust’, understandable but problematic apprehension around official social structures (e.g., government, media, law enforcement, formal healthcare). Economic disadvantage is associated with higher likelihood of pre-existing health conditions that in turn appear to increase COVID-19 risks. For example, this combination of health vulnerabilities and reduced healthcare access is endemic to indigenous communities.

Importantly, stigma goes beyond disfavoured groups and can include people who are also being celebrated for their important role in fighting pandemics (i.e., healthcare workers). Fear of healthcare workers and their potential to spread disease may interact with cultural beliefs about health and illness. If pre-existing negative views about healthcare workers or conspiratorial beliefs that incorporate them are widespread in a given community, the problem increases. At the same time, these kinds of incidents have been reported for many diseases, including COVID-19, across a range of cultural settings, suggesting a degree of universality.

Micro-Level of Individual Psychology

People’s behaviours are based in their beliefs, the behaviours they observe in others (and interpret in light of their beliefs), and the behaviours they believe others expect of them. What a person believes and how they behave is strongly shaped by their cultural context. Individual differences that may in part be rooted in temperament—for example, in attention to health, hygiene, comfort with isolation, tendency to stay home when sick, and so on—are further shaped by local norms.

The tendency towards optimism versus pessimism is a good and relevant example of a dispositional trait that is shaped by cultural context. There is now considerable evidence suggesting that people living in East-Asian cultural contexts tend to hold a cyclical view in which positive and negative experiences tend to oscillate and balance out over time. In other words, a run of good fortune means that one’s luck will soon run out, but also vice versa. People living in Euro-American cultural contexts, by contrast, have a more linear view in which recent past and present experiences predict future experiences.

We can understand a long period of time without a serious pandemic as a run of good fortune, in which case we might expect cultural variations in whether we would expect people to respond with increased or decreased preparation for a future pandemic. In research conducted after the 2002 SARS outbreak, defensive pessimism was associated with traditional Chinese values and predicted increased anxiety about infection but also more consistent health behaviours, such as hand-washing. Unrealistic optimism, in contrast, predicted perceived imperviousness to infection, leading to better mood but also to lower intention to wash hands.

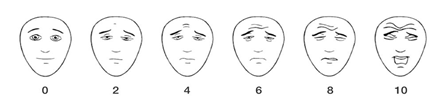

Tendency towards optimism versus pessimism is part of a cluster of personality traits that all share commonality with negative affectivity. Other examples include anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty. Although negative affectivity emerges as an independent personality domain across a wide range of different cultural contexts, there is marked cultural variation in the extent to which negative affectivity is tolerated or minimized. Negative affectivity is associated with risk perception, leading to more distress but also more willingness to take recommended precautions.

Negative affectivity is also associated directly with the likelihood of symptom-like experiences. Anxiety about one’s health leads to increases in self-monitoring for signs of illness; moreover, anxiety itself can generate physiological reactions that might be mistaken for such signs. For example, increased anxiety can be accompanied by increased heart-rate, sweaty palms, trembling, shortness of breath, and so on, all of which could look like signs of illness. Note that some migrants and minority group members might already have elevated anxiety and uncertainty.

Experiences that might be mistaken for disease can thus be produced by a combination of:

- Ideas about pandemic disease symptoms circulating in a given community;

- Culturally-shaped tendencies to monitor particular bodily sensations; and

- Individual differences in negative affectivity.

Moreover, the very fact of paying attention to certain sensations can make them more salient. In some cases, the concern that one might have caught a dangerous disease can generate further anxiety, thus worsening these sensations. These kinds of feedback loops could lead to intra- and inter-group differences in the symptoms that are discussed and expressed.

Conclusion: What Should We Do?

The struggle against COVID-19, will require the ingenuity of biological scientists across a variety of disciplines. Nonetheless, the potential contributions of the behavioural and social sciences should not be underestimated. The pandemic, along with the measures taken to combat it, is shaped in important ways by culture. What, then, are the implications?

An unprecedented number of people worldwide are concerned about the same disease and are experiencing broadly the same distancing measures. As such, there may be a temptation to focus on the similarities. At a minimum, policy-makers, healthcare workers, and the public at large should keep in mind that the pandemic experience may be very different for different people. These differences are shaped by the society in which one lives, the communities of which one is a part, and culturally-shaped individual variations. Complicating matters, appreciation for difference does not mean treating all responses equally when it comes to effectively mitigating a pandemic. Clearly, some cultural patterns are more effective than others.

Nonetheless, understanding that people have reasons for their beliefs and actions is important. Such understanding can help combat stigmatizing attitudes and better tailor strategies to work with different cultural communities. For example, public health officials and other policy-makers might work with religious leaders to spread information about the need to rethink traditional public celebrations. Debunking false information once it has taken hold is extremely difficult. Cultural understanding can help in developing strategies to ‘prebunk’ these ideas: combating this information in advance, in ways acceptable to the target population.

Clinicians, meanwhile, are now practicing in very different ways compared to earlier this year. There has been a major uptake of online service delivery methods, some of which may continue into the foreseeable future. Nonetheless, even when a client is alone on a screen, it is important to keep in mind the web of influences around them. Clients may hold very different culturally-shaped beliefs about the pandemic, different from each other and also different from the clinician.

At the same time, cultural traditions can be a source of resilience, as sources of wisdom about how to make sense of and prepare for uncertainty for example. We should remember, moreover, that interventions are not limited to majority-culture healthcare workers and minority patients. The people on the front-line represent many different cultural groups. As with clients, this can mean specific, underappreciated stressors for minority group healthcare workers—but also potential access to a wider range of cultural resources.

Regardless of whether one is focusing on the laypeople or officials, patients or healthcare workers, we believe it important to be wary of claims that people from a given cultural background will therefore act in a predictable way. Such an approach can inadvertently promote stereotypes, a notable danger during a time of heightened anxieties. The complexities of research in a rapidly changing pandemic context further bolster the argument for caution. Yet, a rapidly shifting landscape fraught with cultural anxieties demands an evidence-based, culturally-attuned approach, and one that can be communicated quickly and effectively.

For cultural and cross-cultural psychologists, the overall message is clear:

- Culture is integral to understanding societal, community, family, and individual responses to pandemics;

- Keeping culture in mind leads to much more nuanced and effective responses to individual circumstances.

We expect many more findings to flesh out this overall message over the next several years. Nonetheless, we have every reason for confidence that such findings will serve to confirm and reinforce these core ideas.

Where do I go for more information?

Provincial, territorial, and some municipal associations of psychology often maintain referral services. For the names and coordinates of provincial and territorial associations of psychology, please visit: https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/PTassociations

This fact sheet has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by Andrew G. Ryder, Associate Professor, Concordia University, Jewish General Hospital; John Berry, Professor Emeritus, Queen’s University; Saba Safdar, Professor, University of Guelph; and Maya Yampolsky, Assistant Professor, Université Laval.

Date: May 27, 2020

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the Psychology Works Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

Canadian Psychological Association

Tel: 613-237-2144

Toll free (in Canada): 1-888-472-0657

Konrad Czechowski

Konrad Czechowski

Angelisa Hatfield has been sitting still for an entire hour. She’s on a Zoom call, and stuck outside on her boyfriend’s porch – the result of having a hole in her own room repaired while she temporarily resides five minutes away. I get the sense that sitting in one place for something like a Zoom call is atypical for Angelisa, who is always on the move.

Angelisa Hatfield has been sitting still for an entire hour. She’s on a Zoom call, and stuck outside on her boyfriend’s porch – the result of having a hole in her own room repaired while she temporarily resides five minutes away. I get the sense that sitting in one place for something like a Zoom call is atypical for Angelisa, who is always on the move. Melissa Mueller is a fighter. Figuratively speaking, that is, in that she’s determined and focused. In Grade 10, a friend mentioned in passing that she was able to talk to Melissa about her problems without fear of everyone else finding out. She decided at that moment, in Grade TEN, she would become a psychologist. Two years later, her Grade 12 math teacher told her she’d never get better marks than 70s. She determined then and there that her goal would be to obtain a PhD. She’s currently a few steps away from obtaining a PhD in psychology.

Melissa Mueller is a fighter. Figuratively speaking, that is, in that she’s determined and focused. In Grade 10, a friend mentioned in passing that she was able to talk to Melissa about her problems without fear of everyone else finding out. She decided at that moment, in Grade TEN, she would become a psychologist. Two years later, her Grade 12 math teacher told her she’d never get better marks than 70s. She determined then and there that her goal would be to obtain a PhD. She’s currently a few steps away from obtaining a PhD in psychology.

Nicole is very much connected to her Polish heritage. She still speaks Polish, although she says it’s getting a little rusty and she needs to keep it up so as not to lose it. She has deep connections with the Polish community in Calgary, and at the University of Calgary where she studies. And she’s actually been to Poland, traveling there with friends as part of a Polish folk dancing group. She was part of that group until her third year of university, when she found her specific passion, and quit to focus on her studies.

Nicole is very much connected to her Polish heritage. She still speaks Polish, although she says it’s getting a little rusty and she needs to keep it up so as not to lose it. She has deep connections with the Polish community in Calgary, and at the University of Calgary where she studies. And she’s actually been to Poland, traveling there with friends as part of a Polish folk dancing group. She was part of that group until her third year of university, when she found her specific passion, and quit to focus on her studies.