Women are disproportionately impacted by the adverse effects of climate change, with women’s intersecting identities exacerbating impact. Erinn Cameron’s research investigates the psychological consequences of climate change for women in Northern rural Ghana and pregnant women living with HIV in semi-urban Western Cape, South Africa. Her work focuses on common mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, and trauma in the context of water scarcity. She also assesses climate anxiety, environmental distress, coping mechanisms, adaptive strategies, and violence against women. For questions, or to learn more about the research, please visit: http://www.erinncameron.com/ or https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Erinn-Cameron

Year: 2023

“Psychology Works” Fact Sheet: The Opioid Crisis in Canada

Understanding the Opioid Crisis

When we think of opioids, such as codeine, morphine, and oxycodone, we often think of the drugs prescribed to help with pain. However, the feelings of joy and well-being brought on by pain relief are also what make opioids an addictive substance, sometimes leading to problematic use beyond their intended medical purposes.

In Canada, the opioid crisis is a devastating public health issue, with opioid-related deaths being persistently on the rise over the last decade. In 2018, it was estimated that nearly 10% of Canadians who were prescribed opioids reported using them in some problematic way. In these cases, problematic use might mean tampering with or taking higher doses of the substance to improve moods or get “high”.

The Risk Factors

So, how did we get here and why is it getting worse? To understand every piece of the puzzle, it is important to consider both systemic (i.e., how does society at-large play a role?) and biopsychosocial risk factors that contribute to the opioid crisis.

Who is Most At-Risk?

While everyone needs to be aware of the addictive risks that come alongside taking a prescribed opiate, certain groups may be particularly vulnerable to problematic opioid use.

- In 2021, 88% of opioid overdoses occurred in three Canadian provinces: BC, Alberta, and Ontario.[1] Larger populations and greater prevalence of chronic homelessness likely contributes to the greater impact of the opioid crisis in these provinces.

- Middle-aged individuals (i.e., between 20 and 59 years of age) account for the majority of opioid-related deaths in Canada (see Footnote 1).

- Men account for most opioid related hospitalizations (68%) and deaths (74%; see Footnote 1) due to their greater likelihood to seek out and use opioids in a risky way. For example, they are more likely to acquire opioids through an illegal source, use drugs beyond the recommended dosage, use more potent drugs (i.e., Fentanyl), or not use drugs via the recommended ingestion method.

- Women may be quicker to progress from use of opioid to dependence, suffer from more severe emotional and physical consequences of drug use, and are more likely to misuse opioids after being prescribed them.

The Impacts of COVID-19

While the COVID-19 landscape is changing quickly, you cannot talk about the Opioid Crisis with considering the impacts of the pandemic. For one, individuals using opioids and other substances are at a at higher risk of contracting COVID-19. Moreover, COVID-19 has significantly worsened the impact of the opioid crisis. In fact, when compared to the year prior to the pandemic (April 2019 – March 2020, 3,747 deaths), opioid-related deaths rose by an estimated 95% (April 2020 – March 2021, 7,362 deaths; see Footnote 1). These troubling statistics have led to what some experts are calling “the shadow pandemic”. Illustrating this, in BC, nearly 4x as many people died of an opioid overdose when compared to COVID-19 deaths.

A number of factors may be contributing to this upsurge in opioid-related deaths during the pandemic, including: 1) more potent alternatives on the toxic drug market; 2) stay-at-home measures reducing access to social/peer support, supervised injection sites, and social services; and 3) increased substance use to cope with isolation, anxiety, and stress (see Footnote 1).

How Can Psychology Help?

Treatment

The frontline treatment for Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) is medication. Specifically, milder “longer-acting” opioids, such as methadone, are used to replace “shorter-acting” opioids (e.g., heroin, oxycodone, fentanyl) to prevent withdrawal symptoms and reduce drug cravings. This occurs without feeling “high” or sleepy, allowing those addicted to opioids to lessen their dependence and stabilize their lives without shocking the system.

Psychosocial approaches to treating OUD tend to be combined with pharmacological treatments. For example, when combined with methadone treatment, several psychological approaches have been shown to be effective at reducing opioid use. These include cognitive behavioural therapy, contingency management, and web-based behavioural interventions.

Opioid dependence often arises after an individual was prescribed opioids as pain killers through the medical system. Thus, psychological interventions for pain management are another important treatment avenue for problematic opioid use. Research shows that the following are effective pain management psychological interventions:

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Mindfulness Meditation

- Clinical Hypnosis

- Biofeedback

- Self‐Management

- Motivational Interviewing

Prevention

Preventative “upstream” interventions, aim to address biopsychosocial risk factors across the life course, such as family/personal history of substance misuse, low socioeconomic status, adverse childhood events (e.g., abuse and/or neglect), coexisting mental health disorders (e.g., anxiety and depression), chronic pain management, poor social support, and history of (ongoing) trauma. This may include targeted public health strategies for reducing the risk of non-medical prescription opioid use.

Harm Reduction

Harm reduction refers to the set of strategies used to minimize negative consequences often related to substance use. For opioid use, this includes services such as safe injection sites where individuals can inject narcotics with healthcare staff on site; take home naloxone kits to help reverse an overdose; infectious disease testing; options for opioid substitution therapies; and supplying clean needles to those injecting drugs. Equitable, same-day access to harm reduction services have proven to be an effective and critical strategy to save lives and can reduce the impact of the opioid crisis.

As COVID-19 continues to worsen the opioid crisis, many top public health officials have called on the federal government to rely on more harm reduction strategies. This may include the decriminalization of the possession of opioids and other illegal drugs for personal use. This would break down the legal barriers preventing individuals with opioid use disorder from accessing opioids. Additionally, providing a “safe supply” for individuals with opioid use disorder is another feasible and effective strategy. This would allow for legal, regulated opioids to be readily available to individuals who need it.

Where Can I Go for More Information?

Canadian Research Initiatives in Substance Misuse Guidelines: https://crism.ca/projects/covid/

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction: https://www.ccsa.ca/

Health Canada Toolkit – COVID-19 and Substance Use: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/toolkit-substance-use-covid-19.html

Letter from the Minister of Health regarding treatment and safer supply: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/minister-letter-treatment-safer-supply.html

You can consult with a registered psychologist to find out if psychological interventions might be of help to you. Provincial, territorial and some municipal associations of psychology often maintain referral services. For the names and coordinates of provincial and territorial associations of psychology, go to https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/PTassociations/.

This fact sheet has been prepared by Madeleine Sheppard-Perkins, MSc, PhD Candidate, Carleton University.

Date: September 2023

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the Psychology Works Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

Canadian Psychological Association

Tel: 613-237-2144

Toll free (in Canada): 1-888-472-0657

[1] Health Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada, and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022). Canada-U.S. Joint white paper: Substance use and harms during COVID-19 and approaches to federal surveillance and response. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. https://www.hhs.gov/overdose-prevention/sites/default/files/documents/canada-us-joint-white-paper-substance-use-harms-during-covid-19.pdf

CPA Appears Before Special Committee on Medical Assistance in Dying (December 2023)

As the federal government gets closer to amending legislation that would permit those with a sole underlying medical condition to seek medical assistance in dying (MAiD), the CPA was invited to appear before the Special Committee (of Members of Parliament and Senators) on Medical Assistance in Dying. CPA President Dr. Eleanor Gittens and CPA Past-President, Dr. Sam Mikhail attended on behalf of the CPA. Read the CPA’s opening remarks. View the meeting (which begins at 1:00).

A health issue, not a criminal one: Decriminalizing illegal substances with Dr. Andrew Hyoun Soo Kim

The CPA’s Working Group on Decriminalization recently published the position paper ‘The Decriminalization of Illegal Substances in Canada’. Dr. Andrew Kim, co-chair of the Working Group, joins Mind Full to discuss how the way we think about drug use informs the way we approach drug use – which should be from a health perspective, not a criminal one.

CPA Releases Telepsychology Guidelines (September 2023)

The CPA Board of Directors recently approved the release of new Guidelines on Telepsychology. The intent of the guidelines is to provide direction and support to Canadian psychologists in order to enable them to practice, ethically, competently, and reflectively while engaging in a virtual environment. The guidelines replace the Interim Ethical Guidelines for Psychologists Providing Psychological Services Via Electronic Media, approved in 2020.

Break the Cycle: Dr. Alex DiGiacomo Completes her Cross-Canada Ride

A month ago, we spoke to Dr. Alex DiGiacomo while she was at the halfway point of her cross-Canada cycling trip. She was raising money and awareness for kids’ mental health in this country, and the major gaps youth have in accessing that care. She has now completed the entire journey, so we invited her back to talk about the big picture, the fundraising effort, the pool noodle, and the incredible community she met and created along the way!

Cash Transfers Reduce Homelessness with Dr. Jiaying Zhao and Amber Dyce

Researchers from UBC teamed up with Foundations for Social Change to conduct a study where they gave a one-time cash transfer of $7,500 to people experiencing homelessness. The results of the study are a first step toward transforming the way we see, and approach, homelessness. We spoke with study lead author Dr. Jiaying Zhao and Foundations for Social Change CEO Amber Dyce about the study itself and the possibilities for ending homelessness.

CPA’s Indigenous Psychology Student Award Program

The purpose of this program is to encourage and support Indigenous (Inuit, First Nations, or Métis) students in psychology in Canadian universities. This is an academic merit-based award that also takes into consideration life factors such as motivation to excel in the field of psychology and level of need in overcoming barriers to attending university.

Application requirements include official transcript, CV or resume, personal statement, and one letter of support.

This year, the CPA welcome applications for one (1) graduate scholarship. Eligible students must be:

- Indigenous;

- a CPA student affiliate in good standing at time of application, and if successful for the duration of the scholarship length; and

- entering graduate studies or be a current graduate student at a Canadian university.

Value of the scholarship is $4000.00 per year, renewable for up to five additional years.

CLOSED for 2025 – Deadline for applications is May 10th, 2025.

“Psychology Works” Fact Sheet: Food Insecurity

Concepts, Definitions and Measures

It is helpful to first think about what food security is.

The United Nations defines food security as when “all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their food preferences and dietary needs for an active and healthy life”.[i]

Household food insecurity is the inadequate or insecure access to food because of financial constraints.[ii] Food insecurity ranges from marginal to severe.

- Marginal food insecurity exists when households worry about running out of food and / or limit their food selection due to cost.

- Moderate food insecurity occurs when people compromise the quality and / or quantity of food consumed due to cost.

- Severe food insecurity occurs when people miss meals, reduce their food intake or, at the most extreme go for day(s) without food.

Recent Trends in Canada

- 6% of people living in the provinces experienced marginal, moderate, or severe food insecurity in 2019.[iii] This included 7.9% who were moderately food insecure and 3.6% who were severely food insecure.

- Food insecurity is highest in the Territories. In 2017/18, almost half (49%) of all households in Nunavut experienced some level of food insecurity, followed by the Northwest Territories (15.9%) and the Yukon (12.6%). Among the provinces, Quebec reported the lowest rate of food insecurity rate (7.4%), and Nova Scotia the highest (10.9%).[iv]

- Although not a perfect indicator of food insecurity, reliance on emergency food assistance can indicate unmet food needs. Between 2019 and 2021, food bank visits in Canada increased by 20.3%, and March 2021 saw 1.3 million visits to food banks.[v]

Who is Food Insecure?

While food insecurity can affect anyone, certain population groups may be more at risk than others.

- In 2019, food insecurity rates were the lowest for persons in senior couples, and highest for persons in female lone-parent families. Single adults and lone-parent families also had a food insecurity rate higher than the national average.5

- Rates of food insecurity are high among post-secondary students, ranging from 42% in 2017[vi] to 57% in 2021.[vii] International students, Indigenous, Latinx, and Black students, 2SLGBTQ+ identifying students, as well as students experiencing precarious housing face a heightened vulnerability to food insecurity.vii

- Indigenous peoples, recent immigrants, and persons with a disability are more likely to face food insecurity; in 2019, the number of Indigenous people moderately or severely food insecure was more than double the overall population.5

- Most food insecure households are in the workforce, and they might be in low-wage jobs and precarious work conditions.

- Households experiencing food insecurity can be both renters and homeowners, though the rate of food insecurity is significantly higher among those living in rental accommodations.[viii]

While there is value in understanding who is more likely to experience food insecurity, it is important to avoid portraying social groups as inherently vulnerable.[ix] The underlying systems that make some people vulnerable must be addressed, such as the legacy of colonization, poverty, and systemic racism. People who experience food insecurity have important perspectives and insights and should be meaningfully included in decision-making processes.

Complex Causes of Food Insecurity

Income Levels

Food insecurity essentially stems from the ability of people to afford the food that they need.[x] Income levels impact food insecurity, including low-wage jobs and precarious work conditions. Insufficient social assistance benefits render households, especially single-person households, at a high risk for being food insecure; in fact, one in five households that rely on government benefits are severely food insecure.4

Cost of Other Basic Needs

Other factors that affect the ability to afford nutritious food include the cost of other basic needs, such as housing, where trade-offs may be made between purchasing food and paying rent or utility bills. Food insecurity is highest among those who rent, with 19% of tenants reported to be moderately or severely food insecure, compared to just 4% of homeowners.[xi]

Unexpected costs or events, such as major repairs or sudden job loss can affect the ability to afford food.

The cost of food itself can also pose a barrier, and recent increases in the price of food may affect lower-income households more severely.[xii]

Social Factors

Social factors such as the lack of transportation to access healthy food, the cultural appropriateness of available and affordable food lack of storage for healthy food, and a lack of time for the preparation of healthy food can also affect food security.

Impacts of Food Insecurity

Food insecurity can cause negative impacts to children’s long-term physical and mental health. It can increase their risk of conditions such as depression and asthma, increase the risk of suicidal ideation, and impact school performance and development.[xiii]

The impacts of food insecurity are experienced by adults as well; they are linked to overall poorer health and chronic conditions (such as depression, diabetes, and heart disease), and can lead to higher medical costs as existing medical conditions are difficult to manage.[xiv]

At its most extreme, food insecurity is also associated with premature mortality, with the average lifespan of adults from severely food insecure households being nine years shorter than those from food secure households.[xv]

Food insecurity also has important social impacts. The inability to provide adequate food can be associated with feelings of shame and a fear of blame. This may lead people to detach themselves from social life. Further, food is often an important form of socializing and the inability to offer food can lead to reduced socialization, particularly for children when parents cannot afford to offer food to childhood friends.[xvi]

Policy and Best Practice in Addressing Food Insecurity

Access to food is a basic human right. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights to which Canada is a signatory states: “The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions.” Article 11 (1). Looking at food insecurity with a human rights approach means that you understand that there are “certain rights that everyone is entitled to, regardless of who they are or where they come from”.[xvii] This approach views the lack of adequate food as a human rights violation, rather than simply the decisions made by individuals, or policies and programs not working.

One important approach to affecting the root causes of food insecurity is to address the link between income and food insecurity. This can be done by improving the financial resources of households with low incomes through specific policy interventions. Policies that increase wages and the quality of employment will reduce the risk of food insecurity among those who are employed. Enhancing Canada’s social protections through appropriate levels of income assistance would further ensure that those requiring income supports are not at risk of food insecurity. In particular, the introduction of a Universal Basic Income would address the problem of food insecurity broadly as food insecurity impacts a diversity of households, and a Basic Income Guarantee can universally reach any household with an inadequate income.[xviii]

Role of Psychology in Addressing Food Insecurity

Psychology has a critical role to play in food insecurity, along with poverty and homelessness, which are closely related.

In terms of mental health services, unfortunately, many people who are food insecure are unable to care for their basic needs. Economically, people who are food insecure are less likely to have sufficient income to pay for privately provided psychological services and are less likely to seek out psychological services. As such, psychologists can work with local housing services, shelter services, community organizations, and food banks – to name a few – to bring their services to these individuals on a sliding scale or pro bono manner. More psychologists should be included in more client-centered, recovery-oriented mental health service delivery at the community level.

Psychology also has a critical role to play in advocacy, particularly as relates to: 1) food availability (a reliable and consistent source of quality food); 2) food access (people have sufficient resources to produce and/or purchase food); 3) food utilization (people have sufficient food and cooking knowledge, and basic sanitary conditions to choose, prepare, and distribute healthy food to their families; and 4) stability (a stable and sustained environment to access and use healthy foods)[xix]. It also has a role to play in advocacy as relates to the, the social determinants of health, the need for affordable housing, the need for access to mental health services, and the interplay between mental health and the social determinants, which are often connected to food insecurity. Considering different system levels, at the micro-level, psychology can liaise with a client’s wider care team and community organizations to advocate for available, accessible, stable, and nutritious food sources. At the macro-level, psychologists can advocate at the community and larger levels for policy change, for the right to food security, universal basic income, funding of affordable and/or rent geared to income housing, increased social assistance, and access to mental health services.

Within academia, community psychology should be taught as part of introductory psychology courses, and more community psychology faculty and researchers should be hired.

In terms of research, psychology can be used to understand:

- Understand attitudes and behaviours of and towards those who experience food insecurity. This can include how to increase support and collective action towards food insecurity, along with identifying possible interventions – both individual and structural.

- Understand social responses to food insecurity that maintain barriers to addressing this problem.

- Evaluate effectiveness of public health initiatives and education to shift social responses to food security.

- Employ different research methodologies and approaches, including but not limited to collaborating with individuals with lived experiences and with Indigenous leaders.

- Exploring the different components of food insecurity, and how they in turn impact individuals of different walks of life.

Psychology can also facilitate forums in which different professions, organizations, and pioneer psychologist leaders in addressing food insecurity, can come together to have interdisciplinary conversations about solutions to food insecurity, and then present any findings via consolidated advocacy efforts to relevant government bodies and agencies.

For Additional Information

Additional information and resources about food insecurity in Canada are available from the following sources.

- PROOF (Food Insecurity Policy Research)

- Food Banks Canada

- Dieticians of Canada

- Community Food Centers Canada

- Food Secure Canada

You can consult with a registered psychologist to find out if psychological interventions might be of help to you. Provincial, territorial and some municipal associations of psychology often maintain referral services. For the names and coordinates of provincial and territorial associations of psychology, go to https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/PTassociations/.

This fact sheet has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by:

The Canadian Poverty Institute

Ambrose University

150 Ambrose Circle SW

Calgary, Alberta T3H 0L5

www.povertyinstitute.ca; povertyinstitute@ambrose.edu

Date: May 2023

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the Psychology Works Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

Canadian Psychological Association

Tel: 613-237-2144

Toll free (in Canada): 1-888-472-0657

hr

References

[i] FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2021. Transforming food systems for food security, improved nutrition and affordable healthy diets for all. Rome: FAO, 2021.

[ii] Tarasuk, V. & Mitchell, A., Household food insecurity in Canada, 2017-18. Toronto: PROOF, 2020.

[iii] PROOF Food Insecurity Policy Research, New food insecurity data for 2019 from Statistics Canada. Toronto: PROOF, 2022.

[iv] Caron, N. & Plunkett-Latimer, J. Canadian Income Survey: Food insecurity and unmet health care needs, 2018 and 2019. Statistics Canada: 2022.

[v] Food Banks Canada, HungerCount 2021. Mississauga: Food Banks Canada, 2021.

[vi] Hamilton, Taylor, D., Huisken, A., & Bottorff, J. L. (2020). Correlates of food insecurity among undergraduate students. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 50(2), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v50i2.188699

[vii] Meal Exchange. (2021). 2021 National Student Food Insecurity Report. Retrieved from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5fa8521696a5fd2ab92d32e6/t/6318b24f068ccf1571675884/1662562897883/2021+National+Student+Food+Insecurity+Report+-3.pdf

[viii] Tarasuk, V. & Mitchell, A., Household food insecurity in Canada, 2017-18. Toronto: PROOF, 2020.

[ix] Sauchyn, D., Davidson, D., & Johnston, M., Prairie Provinces; Chapter 4 in Canada in a Changing Climate: Regional Perspectives Report, Government of Canada: 2020.

[x] Tarasuk, V., Implications of a basic income guarantee for household food insecurity, Thunder Bay: Northern Policy Institute: 2017.

[xi] Statistics Canada. Household Food Insecurity in Canada. Ottawa: Government of Canada: 2020.

[xii] Agri-Food Analytics Lab, Canada’s food price report: 2022. Dalhousie University, University of Guelph, University of Saskatchewan, & The University of British Columbia: 2022.

[xiii] PROOF. Household food insecurity in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto. Available [online] https://proof.utoronto.ca/food-insecurity/. Accessed 18-03-2022.

[xiv] Tarasuk, V., Mitchell, A., & Dachner, N., Household food insecurity in Canada, 2014. Toronto: PROOF: 2016.

[xv] PROOF. Ibid.

[xvi] Purdam, K., E. Garratt and A. Esmail. “Hungry? Food Insecurity, Social Stigma and Embarrassment in the UK.” Sociology. Vol 50, No. 6: 1072-1088. December 2016.

[xvii] Canada Without Poverty, Human rights and poverty reduction strategies. Ottawa: Canada Without Poverty: 2015.

[xviii] Tarasuk, V., Implications of a Basic Income Guarantee for household food insecurity, Thunder Bay: Northern Policy Institute: 2017.

“Psychology Works” Fact Sheet: Poverty

Concepts, Definitions and Measures

The common understanding of poverty is that it involves a critical lack of income that interferes with a person’s ability to meet their basic needs. The experience of poverty, however, is much more complex. The Oxford Multi-Dimensional Poverty Index (MPI) includes the following factors, in addition to income, as constitutive of poverty: quality of work; empowerment; physical safety; social connectedness; psychological well-being, and happiness.[i] The multi-dimensional nature of poverty is reflected in the definition of poverty that was recently adopted by the Government of Canada in its national poverty strategy. According to this definition, poverty is: The condition of a person who is deprived of the resources, means, choices and power necessary to acquire and maintain a basic level of living standards and to facilitate integration and participation in society[ii].

Despite the multi-dimensional nature of poverty, poverty measures continue to be based on income. One important measure of poverty is the Low Income Measure (LIM).

This internationally used measure defines a household as poor if it is earning less than 50% of the median income, adjusted for household size.

In Canada, the Market Basket Measure (MBM) has been adopted as the official measure of poverty. The MBM considers a household poor if its income is insufficient to purchase a basket of goods and services deemed essential for basic human functioning. Income thresholds are adjusted for household size and the region in which one lives.

In 2019, the income thresholds for a family of four (2 adults and 2 children) for major Canadian cities were as follows[iii]:

| Halifax – $46,147 | Winnipeg – $45,164 |

| Montreal – $41,090 | Calgary – $49,462 |

| Toronto – $49,304 | Vancouver – $50,055 |

Incidence of Poverty

According to Canada’s official measure of poverty, 3.73 million Canadians were living in poverty in 2018, accounting for 10.1% of the population.

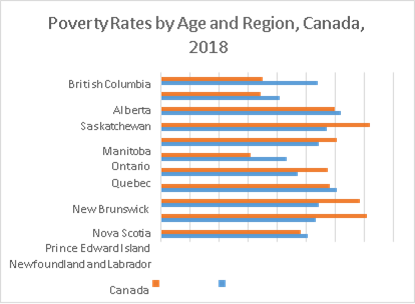

Poverty rates vary by region.

Just under 10% of children under the age of 18 were living in poverty that same year[iv].

Profile

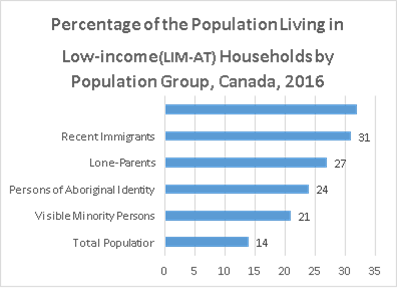

Certain population groups are at greater risk of poverty. In Canada, populations with a higher incidence of poverty include persons living alone, Indigenous persons, racialized persons, recent immigrants, persons with disabilities, and lone-parent families.[v]

Causes of Poverty

Poverty is often thought to result from the deficits of an individual. Lack of education or skills, poor language proficiency, mental health or addictions challenges, lack of financial literacy and poor life choices are some of the factors that can increase a person’s risk of poverty. While these factors do contribute to poverty, it is also important to understand the social conditions in which a person lives.

Where a person is in their life course is an important contributing factor. Stages of life where there is increased dependency, such as childhood or advanced age, increase the risk of poverty. Also at risk are caregivers who support people in dependent situations. Social connections also matter, as those who are isolated or living alone tend to have above average rates of poverty. The stigma attached to poverty can also limit one’s life choices.

Finally, systemic forces act to increase the risk of poverty. Workers employed in precarious positions that are part-time, insecure, and low-waged are at much greater risk of poverty. The lack of recognition of foreign credentials places many immigrants at an increased risk of poverty. Structural conditions including racism, discrimination, patriarchy, and the impacts of colonization are further factors that greatly increase the risk of poverty for people from particular social groups. The inadequacy of Social Assistance benefits further impacts those whose life circumstances require them to rely on income supports, leaving them in deep poverty.

Impacts of Poverty

Poverty comes at a cost. It is estimated that Canada spends between $72.5 and 86.1 billion annually due to the costs associated with poverty[vi] while the annual cost of homelessness is estimated at $7 billion.[vii]

Poverty is associated with reduced levels of trust and social cohesion that affect all of society.[viii]

Poverty also compromises the mental and physical health of adults and children and compromises cognitive functioning.[ix] The developmental impacts on children are particularly important as they can affect future life chances throughout adulthood, affecting biological, cognitive, emotional, and social domains of development. Lack of nutrition, increased experienced stress, decreased maternal supports, increased exposure to trauma and violent neighborhoods interact in a cumulative manner. Noted latent outcomes, resistant to intervention, result from permanent impacts on the developing brain. Specifically, the child is more likely to experience heightened anxiety, emotional difficulties, and difficulties in learning stemming from executive functioning deficits.[x] [xi] These outcomes limit gains in language development, reading and writing and social development. They may also result in problems maintaining healthy relations with parents, peers, and authority figures, such as teachers.[xii] [xiii] [xiv] These cumulative

impacts have been connected to increases in deviant behaviour, early pregnancy, and school dropout, thereby limiting social destinations that increase health and well-being.[xv] [xvi] [xvii]

Policy and Best Practice

Increasingly, poverty is understood as a violation of human rights. Under the international human rights framework of which Canada is a part, people are guaranteed the right to work, fair wages, safe and healthy working conditions, to form or join trade unions, an adequate standard of living, social security, food, clothing, housing, education, health care, and participation in cultural life.[xviii] From this standpoint, addressing poverty involves ensuring that the full array of rights people enjoy are realized. In 2018, Canada adopted a national poverty strategy called Opportunity for All.[xix] This federal strategy has three pillars:

- Dignity: Lifting Canadians out of poverty by ensuring basic needs—such as safe and affordable housing, healthy food, and health care are met

- Opportunity and Inclusion: Helping Canadians join the middle class by promoting full participation in society and equality of opportunity

- Resilience and Security: Supporting the middle class by protecting Canadians from falling into poverty and by supporting income security and resilience

The national strategy acknowledges that freedom from poverty is a human right.

Role of Psychology in Addressing Poverty

Psychology has a critical role to play in addressing poverty, along with homelessness and food insecurity which are often outcomes/consequences of poverty.

In terms of mental health services, unfortunately, many people who are experiencing poverty are unable to care for their basic needs and may subsequently experience in transient circumstances compounded by unmanaged mental health, trauma, or substance use challenges. Economically, people who are experiencing poverty do not have sufficient income to pay for privately provided psychological services, nor may they know where to begin in terms of finding a psychologist. As such, psychologists can work with local housing, shelter, or community services to bring their services to where the impoverished are, and if able, to do so on a sliding scale or pro bono manner. More psychologists should be included in more client-centered, recovery-oriented mental health service delivery at the community level.

Psychology also has a critical role to play in advocacy, particularly as relates to the anti-poverty initiatives, social determinants of health, the need for affordable housing and food security, the need for access to mental health services that are covered under provincial health plans, and the interplay between mental health and the social determinants. Considering different system levels, at the micro-level, psychology can liaise with a client’s wider care team and community organizations to ensure their core health and psychological needs are met. At the macro-level, psychologists can advocate at the community and larger levels for policy change, for funding of affordable and/or rent geared to income housing, food security, increased social assistance, access to mental health services, and coverage of psychological services under provincial health plans.

Within academia, community psychology should be taught as part of introductory psychology courses, and more community psychology faculty and researchers should be hired.

In terms of research, psychology can be used to understand:

- Understand attitudes and behaviours of and towards those who experience poverty. This can include how to increase support and collective action towards combatting poverty, along with identifying possible interventions – both individual and structural.

- Understand social responses to poverty that maintain barriers to addressing this problem.

- Evaluate effectiveness of public health initiatives and education to shift social responses to poverty.

- Employ different research methodologies and approaches, including but not limited to collaborating with those with lived experience and with Indigenous leaders.

- Exploring how poverty impacts individuals of different walks of life.

Psychology can also facilitate forums in which different professions, organizations, and pioneer psychologist leaders in addressing poverty, can come together to have interdisciplinary conversations about solutions to poverty, and then present any findings via consolidated advocacy efforts to relevant government bodies and agencies.

For Additional Information

- National Advisory Council on Poverty https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/poverty-reduction/national-advisory-council.html

- Canadian Poverty Hub povertyhub.ca

- Canada Without Poverty cwp-csp.ca

- Tamarack Institute for Community Engagement tamarackcommunity.ca

You can consult with a registered psychologist to find out if psychological interventions might be of help to you. Provincial, territorial and some municipal associations of psychology often maintain referral services. For the names and coordinates of provincial and territorial associations of psychology, go to https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/PTassociations/.

This fact sheet has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by:

The Canadian Poverty Institute

Ambrose University

150 Ambrose Circle SW

Calgary, Alberta T3H 0L5

www.povertyinstitute.ca; povertyinstitute@ambrose.edu

Date: May 2023

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the Psychology Works Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

Canadian Psychological Association

Tel: 613-237-2144

Toll free (in Canada): 1-888-472-0657

References

[i] Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative. https://ophi.org.uk/research/multidimensional- poverty/ Accessed 19 January 2022.

[ii] Government of Canada. 2018. Opportunity for All: Canada’s First Poverty Reduction Strategy Ottawa: Government of Canada.

[iii] Statistics Canada. Table 11-10-0066-01 Market Basket Measure (MBM) thresholds for the reference family by Market Basket Measure region, component, and base year. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1110006601

[iv] Statistics Canada. Table 11-10-0135-01 Low-income statistics by age, sex, and economic family type. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1110013501

[v] Statistics Canada. 2016. Census of Canada.

[vi] Government of Canada. 2010. Federal Poverty Reduction Plan: Working In Partnership Towards Reducing Poverty In Canada. Report of the Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities. Ottawa: Government of Canada.

[vii] Gaetz, S., J. Donaldson, T. Richter and T. Gulliver-Garcia. 2013. The State of Homelessness in Canada 2013. Toronto: The Canadian Observatory on Homelessness and the Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness.

[viii] Ross, C. 2011. “Collective Threat, Trust and the Sense of Personal Control.” Journal of Health and Social Behaviour 52, no. 3 (September).

[ix] Mikkonen, J., & Raphael, D. 2010. Social Determinants of Health: The Canadian Facts. Toronto: York University School of Health Policy and Management.

[x] Anasuri, S. 2017. Children living in poverty: Exploring and understanding its developmental impact. Journal Humanities and Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) 22, (6), Ver. 9 (June. 2017) PP 07-16.

[xi] Barch, D., Pagliaccio, D., Belden, A., Harms, M. P., Gaffrey, M., Sylvester, C. M., Tillman, R., & Luby, J. (2016). Effect of Hippocampal and Amygdala Connectivity on the Relationship Between Preschool Poverty and School-Age Depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(6), 625–634.

[xii] Anasuri. 2017. Ibid.

[xiii] Chaudry, A., & Wimer, C. 2016. Poverty is Not Just an Indicator: The Relationship Between Income, Poverty, and Child Well-Being. Academic Pediatrics, 16 (3 Suppl), S23–S29.

[xiv] Hyde, L. W., Gard, A. M., Tomlinson, R. C., Burt, S. A., Mitchell, C., & Monk, C. S. 2020. An ecological approach to understanding the developing brain: Examples linking poverty, parenting, neighborhoods, and the brain. American Psychologist, 75(9), 1245–1259.

[xv] Anasuri. 2017. Ibid.

[xvi] Larson C. P. (2007). Poverty during pregnancy: Its effects on child health outcomes. Paediatrics & Child Health, 12(8), 673–677.

[xvii] Maggi, S., Irwin, L. J., Siddiqi, A., & Hertzman, C. (2010). The social determinants of early child development: an overview. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 46(11), 627–635.

[xviii] Canada Without Poverty. n.d. Human Rights and Poverty Reduction Strategies: A Guide to International Human Rights Law and its Domestic Application in Poverty Reduction Strategies. Ottawa: Canada Without Poverty.

[xix] Government of Canada. 2018. Ibid.

“Psychology Works” Fact Sheet: Homelessness

Concepts, Definitions and Measures

The condition of homelessness is a continuum that ranges from being unsheltered to emergency sheltered, to provisionally accommodated, to those at risk of homelessness.

- Unsheltered: People who reside in places not meant for human habitation, such as cars, parks, abandoned buildings, alleys, and streets.

- Emergency Sheltered: People residing in shelters, including those fleeing domestic violence.

- Provisionally Sheltered: People living in insecure accommodations, such as staying temporarily with family or friends[i].

- At risk of homelessness are said to be in “Core Housing Need”. According to Statistics Canada “A household is said to be in ‘core housing need’ if its housing falls below at least one of the adequacy, affordability or suitability standards and it would have to spend 30% or more of its total before-tax income to pay the median rent of alternative local housing that is acceptable (meets all three housing standards).”[ii] Affordability is achieved when housing costs less than 30% of family income. To meet the standard for adequacy, no major repairs to the dwelling are required and the household has sufficient income to manage expenses including major repairs. Housing is considered suitable when it has enough bedrooms appropriate for the size and makeup of the household.

It is also important to distinguish between chronic and episodic homelessness.

- Chronically homeless: Those who have been homeless for six months or more

- Episodically homeless: Those who experienced three or more episodes of homelessness that lasted less than six months[iii].

Incidence and Trends

There are an estimated 35,000 Canadians who are homeless across Canada on any given night, and over 235,000 experience homelessness at some time throughout the year.

- The population of provisionally housed could further include as much as 50,000 on any night[iv], while an estimated 8% of the general population have been provisionally housed at some point in their life[v]. Over half (55%) of those who are provisionally housed were in the situation for more than one month.

- Among those who relied on emergency shelters, the average shelter stay is around 10 days[vi].

- Approximately two-thirds (60%) of those experiencing homelessness are chronically homeless[vii].

- Across Canada, 1,644,900 households were reported to be in core housing need in 2018 and therefore at some risk of homelessness[viii].

Profile of Persons Experiencing or At Risk of Homelessness

Certain groups of people remain at greater risk of homelessness than others.

- Across Canada, Indigenous persons account for a disproportionate share of those who are unsheltered or provisionally housed. Indigenous persons account for between 28 and 34% of shelter residents, despite accounting for just 4.3% of the total population[ix]. It is also estimated that 18% of Indigenous persons have been provisionally housed at some point in their life[x].

- Roughly half (52%) of persons experiencing homelessness in Canada are adults between the ages of 25-49.

- Youth, however, constitute an important group, with those between the ages of 13 and 24 accounting for an estimated 19% of the population that is homeless. Of youth experiencing homelessness, roughly one in five identify as LGBTQ2S[xi].

- Over one quarter (27%) of the population that is homeless are women[xii].

Diverse and Complex Causes of Homelessness

Affordability of Housing

One critical factor is the affordability of housing. This is a combination of inadequate income and rapidly increasing costs for both rental and owned accommodations. Related to this is insufficient investments in social housing resulting in significant waiting lists among those in need of affordable accommodation. Insufficient income support benefits are a further contributing factor as those receiving social assistance are typically unable to afford market rents. The lack of affordable accommodation increases vulnerability to homelessness caused by other factors.

Violence and Abuse

Domestic violence can lead to homelessness, particularly among women. Those fleeing situations of violence may be unable to find affordable alternate accommodation. Meanwhile, emergency shelters for domestic violence survivors are often at capacity, while the allowable time to remain in shelter is restricted.

Among youth, situations of emotional, physical, or sexual abuse in the home can also lead to youth fleeing into homelessness.

Mental Health and Substance Abuse

Mental health and substance abuse issues also contribute to homelessness. This is in part due to policies of de-institutionalization and reductions in community supports for people experiencing these issues. Similarly, poorly coordinated transitions from institutional care, such as health, corrections, or child welfare, often leave people without supports and at risk of homelessness.

Personal Circumstances

Personal circumstances can further result in homelessness. Family or relationships breakdown, not necessarily because of violence, is a risk factor, including experiences of trauma or abuse in childhood.

Traumatic or disruptive events, such as job loss, fire, or onset of a mental or physical disability can also result in homelessness.

Finally, the risk of homelessness cannot be dissociated from other broader patterns of socio-economic disadvantage and marginalization including racism, patriarchy, and colonization.

Impacts of Homelessness

There are a variety of individual and societal impacts of homelessness.

- Economically, it is estimated that the cost of homelessness in Canada is roughly $7B annually[xiii].

- At an individual level, persons who are homeless experience reduced mental and physical health due to compromised immune systems, poor hygiene and nutrition, crowded living conditions, or risks from sleeping outside.

- Persons who are homeless are also at greater risk of violence. A report on the safety of people sleeping rough in Toronto found that about one third had been hit, kicked, or experienced some other form of violence. A similar proportion had been the target of things being thrown at them, while almost one in ten had been urinated on while homeless[xiv]. An earlier (1993) report found that over one-in-five homeless women (21%) reported having been raped in the previous year[xv].

- It is also estimated that homelessness can reduce life expectancy by as much as 40%[xvi].

Policy and Best Practice in Addressing Homelessness

The right to housing is increasingly being used as the framework for understanding homelessness in Canada. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights guarantees the right to housing. In Canada, the right to housing was recently affirmed in the National Housing Strategy, which includes the establishment of a Housing Advocate. Despite this, housing is not a guaranteed right in either The Constitution Act (1867), or the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, nor is it protected by the provinces.

The National Housing Strategy re-establishes a commitment by the federal government to work toward the provision of adequate and affordable housing in line with Canada’s international human rights obligations. This is an important reassertion of the federal role in housing following the withdrawal of the government from affordable housing in the 1990’s. Over the past two decades, municipalities have taken a leading role in addressing homelessness. Many cities have developed Ten Year Plans to End Homelessness. Over that time, “Housing First” has emerged as a dominant philosophy in addressing homelessness. Housing First is based on the principle of the right to housing and aims to move chronically homeless people from the streets or shelter into housing immediately, while providing wrap-around supports. It assumes that stabilizing people’s lives first will provide a better environment from which other life challenges, such as addictions, can be better addressed.

Role of Psychology in Addressing Homelessness

Psychology has a critical role to play in addressing homelessness, along with poverty and food insecurity, which are often precursors to homelessness.

In terms of mental health services, unfortunately, many people who are at risk of or who are homeless are unable to care for their basic needs and will continue in transient circumstances due to unmanaged mental health, trauma, or substance use challenges. Economically, people who are at risk of or who are homeless do not have employment which provides coverage for psychological services, do not have sufficient income to pay for privately provided psychological services, nor may they know where to begin in terms of finding a psychologist. As such, psychologists can work with local housing or shelter services to bring their services to where the homeless, and if able, to do so on a sliding scale or pro bono manner. More psychologists should be included in more client-centered, recovery-oriented mental health service delivery at the community level.

Psychology also has a critical role to play in advocacy, particularly as relates to the social determinants of health, the need for affordable housing, the need for access to mental health services, and the interplay between mental health and the social determinants. Considering different system levels, at the micro-level, psychology can liaise with a client’s wider care team and community organizations for access to housing. At the macro-level, psychologists can advocate at the community and larger levels for policy change, for funding of affordable and/or rent geared to income housing, increased social assistance, and access to mental health services.

Within academia, community psychology should be taught as part of introductory psychology courses, and more community psychology faculty and researchers should be hired.

In terms of research, psychology can be used to understand:

- Understand attitudes and behaviours of and towards those who experience homelessness. This can include how to increase support and collective action towards decreasing homelessness, along with identifying possible interventions – both individual and structural.

- Understand social responses to homelessness that maintain barriers to addressing this problem.

- Evaluate effectiveness of public health initiatives and education to shift social responses to homelessness.

- Employ different research methodologies and approaches, including but not limited to collaborating with Indigenous leaders, as well as incorporating Indigenous teachings and knowledge.

- Exploring how homelessness (or being at risk of homelessness) impacts individuals of different walks of life.

Psychology can also facilitate forums in which different professions, organizations, and pioneer psychologist leaders in addressing homelessness, can come together to have interdisciplinary conversations about solutions to homelessness, and then present any findings via consolidated advocacy efforts to relevant government bodies and agencies.

For Additional Information

Additional information and resources about homelessness in Canada are available from the following sources.

- Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness (CAEH)

- Canadian Mortgage and Housing Company (CMHC)

- Centre for Equal Rights in Accommodation (CERA)

- Homeless Hub

- National Right to Housing Network

- National Housing Strategy: A Place to Call Home

You can consult with a registered psychologist to find out if psychological interventions might be of help to you. Provincial, territorial and some municipal associations of psychology often maintain referral services. For the names and coordinates of provincial and territorial associations of psychology, go to https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/PTassociations/.

This fact sheet has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by:

The Canadian Poverty Institute

Ambrose University

150 Ambrose Circle SW

Calgary, Alberta T3H 0L5

www.povertyinstitute.ca; povertyinstitute@ambrose.edu

Date: November 2022

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the Psychology Works Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

Canadian Psychological Association

Tel: 613-237-2144

Toll free (in Canada): 1-888-472-0657

References

[i] Gaetz, S., E. Dej, T. Richter, and M. Redman. 2016. The State of Homelessness in Canada. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness.

[ii] Statistics Canada. 2017. Dictionary, Census of Population, 2016. Ottawa: Ministry of Industry.

[iii] Government of Canada. 2019. Everyone Counts 2018: Highlights – Preliminary Results from the Second Nationally Coordinated Point-in-Time Count of Homelessness in Canadian Communities. Ottawa: Employment and Social Development Canada.

[iv] Gaetz, S., E. Dej, T. Richter, and M. Redman. 2016. The State of Homelessness in Canada. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness.

[v] Advocacy Centre for Tenants Ontario www.acto.ca

[vi] Gaetz et al. 2016. Ibid.

[vii] Government of Canada. 2019. Everyone Counts 2018: Highlights – Preliminary Results from the Second Nationally Coordinated Point-in-Time Count of Homelessness in Canadian Communities. Ottawa: Employment and Social Development Canada.

[viii] Statistics Canada. Table 46-10-0037-01 Dimensions of core housing need, by tenure including first-time homebuyer and social and affordable housing status

[ix] Gaetz et al. 2016. Ibid.

[x] Advocacy Centre for Tenants Ontario www.acto.ca

[xi] Government of Canada. 2019. Everyone Counts 2018: Highlights – Preliminary Results from the Second Nationally Coordinated Point-in-Time Count of Homelessness in Canadian Communities. Ottawa: Employment and Social Development Canada.

[xii] Gaetz et al. 2016. Ibid.

[xiii] Gaetz, S., J. Donaldson, T. Richter and T. Gulliver-Garcia. 2013. The State of Homelessness in Canada 2013. Toronto: The Canadian Observatory on Homelessness and the Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness.

[xiv] Safe Haven Toronto. “Attacks On Homeless People Make Sleeping Rough Even Rougher.” October 13, 2019. https://www.haventoronto.ca/single-post/2019/10/13/Attacks-On-The-Homeless

[xv] Crowe C, Hardill K. Nursing research and political change: the street health report. Can Nurse. 1993 Jan;89(1):21-4.

[xvi] Webster, P. 2017. “Bringing homeless deaths to light”. CMAJ. March 20, 2017 189 (11)

CPA Releases Recommendations for the Decriminalization of Illegal Substances in Canada (September 2023)

Led by Co-Chairs, Dr. Andrew Kim, Dr. Keira Stockdale and the late Dr. Peter Hoaken, the CPA Board of Directors recently approved a position paper The Decriminalization of Illegal Substances in Canada developed by the Working Group on Decriminalization. In addition to seven actionable recommendations for governments and relevant stakeholders, the report calls for criminal penalties associated with simple possession of illegal substances be removed from the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, and strongly recommends that the determination of the quantity of “personal use” should be made in consultation with all relevant stakeholders, including people with lived and living experience with substance use. See our news release.

CJEP Open Call for Special Issues

CJEP is now issuing an open call for special issue proposals, to be considered for three deadlines per year by the senior editorial team—September 15, December 31, and June 15. Note that if you are considering submitting a special issue proposal, you are welcome to optionally reach out to Editor Debra Titone ahead of time to discuss and refine your idea.

Each proposal should be no more than two pages, single spaced, and should address the following.

- title of special issue;

- description and rationale of special issue;

- guest editor(s) names, affiliations, and description of their background relevant to organizing the special issue;

- will the special issue be invited papers or involve and open call, and why (note we prefer open calls where possible);

- list of hypothetical researchers in Canada and beyond who might submit a paper to the special issue; and

- anticipated deadline for letters of intent to submit, and final manuscript submission.

Article Submissions: https://www.editorialmanager.com/cep/default2.aspx

Federal Government 2024 Pre-Budget Consultations (August, 2023)

In lead up to the federal government’s 2024 Budget, the CPA submitted its Brief to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance which contains four financial asks which focus on improved access to care across the public and private sectors, creating more training positions for psychology, and increasing research funding to the Tri-Councils and funding for students and post-doctoral Fellows. The Canadian Alliance on Mental Illness and Mental Health (CAMIMH), of which the CPA is a founding member, also submitted a Brief.

New Position Statement: Promotion of Gender Diversity and Expression and Prevention of Gender-Related Hate and Harm

The Canadian Psychological Association (CPA) through its Code of Ethics and policy statements, has long held a commitment to human rights, social justice, and the dignity of persons. Despite this commitment, echoed in amendments to Canada’s Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code, and in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, gender-based stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination continue to persist across social systems and services (e.g., education, health, justice).

With the rise of gender minority hate and violence worldwide, this policy statement outlines the discrimination that people of gender minority face, as well as the changes that need to be made to redress it. The CPA commits to helping to bring about these changes and calls on legislators, policy makers, and agencies and individuals who deliver health and social services to assert their commitments to join us.

View the full Position Statement here (PDF).

View all of the CPA’s Position and Policy Statements here

Making connections: Shanique Victoria and Black Mental Health Canada

For many Black Canadians, their first contact with the mental health system is through the criminal justice system. Both systems that have historically marginalized and victimized minority communities, and in many ways are still doing so. Black Mental Health Canada (BMHC) is one of the organizations trying to change this paradigm. Shanique Victoria, Research Project Lead at BMHC, joins Mind Full to tell us more.

Authoritative, authoritarian and everything in between: Parenting Styles with Dr. Christina Rinaldi

How do psychologists look at parenting and parenting styles? And is there one style that tends to work better than others? We invited Dr. Christina Rinaldi to Mind Full to help answer some of the burning questions parents might have.

“Psychology Works” Fact Sheet: Retirement

What is “retirement”?

Retirement typically refers to an age-related reduction in, or withdrawal from employment. The word “retirement” conjures up many different things to people. To some, it is a long-awaited reward for a lifetime of work. To others it is a signal of the end of one’s usefulness and relevance in the world. Depending on the point of view taken, retirement can raise feelings of relief and happiness or of sadness and anxiety. In reality, there is no one specific way to retire. Retirement can take on many forms – from a continuation of working with fewer hours to employment in a different occupation to a complete withdrawal from the workforce.

Historically, workers continued to work until their death due to a low life expectancy and an absence of pensions or social security. Germany was the first country to introduce retirement benefits in the late 19th century. Chancellor Otto von Bismarck argued that older workers who were no longer able to work deserved to be supported by the state. He also, however, wanted older workers to leave the workforce to make room for the large number of unemployed youths at the time. Since then, most other countries have adopted some type of retirement program.

Do you have to retire?

In Canada, there is no longer a mandatory retirement age, so this means that, with few exceptions (i.e., pilots), employees are protected from being forced from their jobs solely based on their age. Employers must provide a bona fide reason for terminating an employee at any age, including after 65. That being said, an older worker may face ageism in the workplace and feel pressured to retire earlier than they would like. In that case, it may be worthwhile to have a discussion with someone in Human Resources or to seek legal consultation.

The process of retirement

Pre-Retirement phase

Retirement is no longer seen as a one-time event. It is a process that begins long before an employee leaves the workforce. The Pre-retirement phase usually begins around mid-career when people start thinking about what life would be like after they retire. Important considerations for this phase are how much savings are in place and the status of one’s health and relationships. This is the time to identify any shortcomings in these areas and to take action to address them. Starting to plan for retirement at this stage will greatly increase the chance of having a successful retirement.

Transition phase

Once the retirement date arrives, the Transition phase begins. The early stages of this phase can create a “honeymoon” effect in which retirees bask in the freedom of no longer being tied to a job. Alternatively, it can cause anxiety by creating a feeling of being unmoored from the structure of the workplace. Isolation and boredom can creep in as well as worry about how to fill in all that free time. This is a time when seeing a psychologist can be of assistance in getting through this stage of life if the stress feels overwhelming.

Adaptation phase

Eventually, the Adaptation phase is reached at which point most people no longer work and settle into a new lifestyle that fits them and provides a sense of contentment.

When is the right time to retire?

Deciding when to retire can be one of the most important and difficult decisions to make. There are many things to take into consideration. Talking to friends or colleagues who have successfully retired may provide useful information. Consider finding or taking a seminar on retirement; in addition to providing information on retirement benefits, they typically also discuss some of the social and psychological issues that retirees may face.

Some of the most important questions to ask yourself when considering retirement are:

Do you have enough money?

This is a tough question to answer and is often the first thing people think about when contemplating retirement. How much money do you need to fund the lifestyle that you want? Will the money you have be enough for the rest of your life? The answer to these questions may be different for those with a pension versus those who are self-funding their retirement. Another consideration is when is the best time to start taking your Canada Pension Plan (CPP), if you are eligible, or Old Age Security (OAS)?

There are financial specialists who can help you with this type of decision-making. Ultimately, it will come down to you deciding what it will take to fund your lifestyle (as well as possible unforeseen expenses) and then calculating your anticipated income to determine if it will cover it. You can expect some decreases in expenses that are associated with employment such as commuting costs but there may also be some increases in necessary expenses if, for example, you will be losing health benefits post-employment. For many, a major source of anxiety, though, comes from the fact that they don’t know what the future holds for them or what the financial impact will be on them, or possibly, their family members and legacy/estate.

In terms of retirement satisfaction, people are unhappy when they don’t have enough money to support the lifestyle that they want to live in retirement. Beyond that, increased income in retirement is not associated with an increase in happiness[1].

What about your health?

In general, the state of your health is one of the most significant factors in determining your retirement satisfaction. It is difficult to enjoy your retirement if you are in poor health, either physically or mentally, because of the possible limits that poor health can put on your lifestyle. There are factors that affect your health status that are beyond your control, however, maintaining a healthy lifestyle, as much as possible, starting from before you retire, can help contribute to a happy retirement.

Your state of health may also be a determining factor in your decision on when to retire. It is possible that ill health will force you out of the workforce. People who retire for this reason are often not happy ending their careers this way. They may not feel ready to retire and wish to continue working but they cannot.

Because they intended to keep working, they may not have plans in place for this early retirement. Coming to grips with this new reality is very stressful. If you find yourself in this situation, professional assistance with a psychologist may help ease you through this transition by helping you find ways to manage stress and the negative feelings associated with it.

Where does your family fit in?

Research in Canada has found that people who are married or in a relationship are more satisfied in retirement than those who are separated, widowed, divorced, or never married1. This was true for both men and women. However, all seniors, regardless of marital status were more satisfied with their lives if they got to spend the amount of time that they wanted with family members. When this is taken into consideration, marital status is less important in accounting for life satisfaction. Therefore, regardless of marital status, spending the amount of time that you would like with loved ones can bring a measure of joy to your retirement life. For some retirees, this might even involve a discussion of relocating to be closer to family members.

For retirees in relationships, retirement satisfaction is associated with how much your partner is involved with your retirement decision and whether you and your partner have shared goals for your retirement years. Having your partner involved in your retirement planning can also lead to an easier transition into retirement. Partners can be a social resource in retirement by providing support at a time when you may be losing other social supports and by facilitating your goals. They also provide a sense of continuity at a time when many other aspects of your life are changing. Therefore, an important step in your retirement planning is to involve your partner directly in your plans and to try to align your visions of retirement together.

What will your social life look like?

While working, you spend more time with our co-workers than you do with other people in your social circle. You see them and interact with them daily. When you retire, you no longer have that daily contact with others and may feel this loss. Not having the workplace in common anymore, nor the working lifestyle, may also lead to a drift away from some of your old working friends. This may be a time to meet new people whose lifestyles are now more like your new one – people with whom you can socialize with or engage in activities with during the day. Feelings of isolation in retirement can lead to unhappiness. Finding new ways to fill the gap in your social life can contribute to retirement satisfaction. Volunteering or engaging in activities that you love in the community will put you into contact with others who share your interests and provide a potential pool of new friends.

What do you do with all that time?

This is a very common concern for people considering retiring. It is easy to see how to use up some of it but 40 hours. And if you retire at 65, you may well have 20 or 30 years left to live.

For some retirees, the answer is to embark on a different career altogether or to engage in part-time work. You have the freedom now to work on your own terms – when and where you’d like, in a position that may be less stressful or time-consuming and yet keep you connected to the working world. Employment will also add a boost to your retirement income.

Retirement is also an opportunity to engage in activities that you may not have had the time for while working. Such activities may involve learning a new skill or travelling to places that you’ve always wanted to see or giving back to the community with some type of volunteer work. Among older Canadians, engaging in activities reduces psychological distress such as depression and anxiety[2]. However, it is not just the act of participation that counts, but the fact that you feel engaged or connected to others. This means that you are spending time with people with whom you feel close to and can count on for help and support. These are important factors in reducing stress.

Identity

Identity issues can cause stress when transitioning from employment to retirement. How do you explain who you are without explaining what you do? Who are you if you are no longer a teacher, dentist, salesperson etc.? After being someone who had been in a clearly defined role in society while employed, retirement can result in a sense of loss of identity and a challenge to create a new one for yourself. This process is more difficult for people who see themselves as having only one identity – usually their work one. It is easier to forge a retirement identity for yourself if you already see yourself in multiple roles before you retire. Therefore, it is helpful to become involved in more than one major life activity to ease the transition to retirement.

Meaning

Throughout your life, you were preoccupied with, at first, your education and then your employment. You may have raised children or been involved in other worthwhile activities. Thus, you had a sense of purpose which provided meaning to your life. In retirement, much of those things are now finished and you may feel a void in your life. What is the next step? The answer to this question is up to each individual. A fear of this step and an inability to see what comes next may keep someone in the workforce longer than they should be. It can also lead to denial of the fact that, eventually, everyone must retire. A lack of acceptance of this fact leads to a lack of planning and preparation and thus a more stressful and unhappy retirement experience. It may also result in external circumstances dictating when you retire, for example, ill health or the need to care for a family member. Ideally, for a happy and successful retirement, you will be the one deciding when to retire. Not being in control of such a major life decision can lead to a very stressful and unhappy retirement.

Retirement is a time to focus your time and energy on things that are meaningful and give value and purpose to your life, other than providing an income. For some people, the transition to retirement can be a difficult process to get through – with the many changes and unknowns creating stress and anxiety. If you are struggling with finding value and meaning in your life and are experiencing prolonged periods of sadness and worthlessness, it may be time seek assistance. A psychologist can help you re-orient to a new way of living and help you find meaning and, ultimately, contentment with your new lifestyle. It is important to take whatever steps are necessary to get the most out of this important and rewarding stage of life.

For More Information

Lamarche, V. M. For couples, a happy retirement requires shared goals. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/love-chaos/202202/for-couples-a-happy-retirement-requires-shared-goals

Dychtwald, K. & Morison, R. (2020). What retirees want: A holistic view of life’s third age. John Wiley & Sons.

Martin, T. & Dagys, A. (2019). The Canadian’s guide to retirement planning. John Wiley & Sons.

Pascale, R., Primavera, L.H., & Roach, R. (2012). The retirement maze: What you should know before and after you retire. Rowman & Littlefield

Waldinger, R. & Schultz, M. (2023). The good life: Lessons from the world’s longest scientific study of happiness. Simon & Schuster.

You can consult with a registered psychologist to find out if psychological interventions might be of help to you. Provincial, territorial and some municipal associations of psychology often maintain referral services. For the names and coordinates of provincial and territorial associations of psychology, go to https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/PTassociations/.

This fact sheet has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by Jean Haley Ph.D., C. Psych. (Retired) on behalf of the CPA’s Section of Psychologists and Retirement.

Date: February 2023

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the Psychology Works Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

Canadian Psychological Association

Tel: 613-237-2144

Toll free (in Canada): 1-888-472-0657

[1] Uppal, S. & Barayandema, A. Life sa#sfac#on among Canadian seniors. Release date: August 2, 2018. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2018001/article/54977-eng.htm

[2] Mackenzie, C. S. & Abdulrazaq, S. (2021). Social engagement mediates the relationship between participation in social activities and psychological distress among older adults. Aging and Mental Health, 25 (2), 299-305.

Mind Full, a CPA Podcast: Meet Dr. Lisa Votta-Bleeker, The CPA’s new CEO

The CPA has a new CEO! Meet Dr. Lisa Votta-Bleeker on the latest episode of our podcast Mind Full.

Understanding Developmental Coordination Disorder with Dr. Paulene Kamps

Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) affects up to one in 15 people, but it is not a well-known diagnosis. Many symptoms (difficulty tying shoes or holding a pencil, clumsiness) can be misunderstood. DCD expert Dr. Paulene Kamps tells us more.

CPA Releases Report on Psychology and Employer-Based Mental Health Benefits (May 2023)

To better understand the value employees’ place on accessing psychological services and how employers perceived the value of their employee health benefit plans, the CPA released Employees, Employers & the Evidence…The Case for Expanding Coverage for Psychological Services in Canada. The report summarizes the available clinical evidence in support of psychological services, the business case/return-on-investment for employers, and a number of leading practices by employers. Read the news release and full report.

Sports, gender, and…pickleball? With Sara Weiss

We’ve spoken a fair amount on Mind Full the last few months about many aspects of gender diversity. Unfortunately, the misinformation and hatred directed at transgender and gender diverse people in both the public and political spheres continues to escalate.

Today, we wanted to speak with someone directly affected by this vitriol. Sara Weiss was targeted for her participation in the US Open pickleball tournament, and joins Eric to discuss the facts, the fiction, and the impact this has had on her directly.

Tailored Insurance Solutions for CPA Members

Members have access to comprehensive insurance coverage that meets the unique practice risk needs of psychological practitioners, including:

Members have access to comprehensive insurance coverage that meets the unique practice risk needs of psychological practitioners, including:

- Professional liability Insurance (PLI) and Commercial General Liability (CGL)

- Business Professional Liability Insurance

- Business Commercial General Liability

- Contents/Crime/Business Interruption coverage

- Business Package Insurance

- Cyber Security & Privacy Liability

- Employment Practices Liability

- Legal Services Package

- Personal Legal Solutions

- Business Legal Solutions

- 24 Hour Accident coverage