Gina Ko is a psychologist in Alberta who has been working in anti-racism for a while. She realized many of her colleagues in that space had great stories to share, so she started the podcast Against The Tides Of Racism. You can find her podcast on Spotify, or at the website here:

www.againstracismpodcast.com/

Year: 2021

Advocacy, Policy, And Public Affairs For Psychologists With Glenn Brimacombe

Glenn Brimacombe is the director of Policy and Public Affairs at the Canadian Psychological Association, and has just created an advocacy guide for the CPA’s member psychologists to help them in their efforts to speak with MPPs and get their message out. He joins Eric (who just created a companion Working-With-The-Media guide for members) to discuss advocacy and the role of psychologists in public policy making.

Launch of Members Only Advocacy Toolkit for Psychology

In addition to the advocacy work that the CPA undertakes on your behalf, the Association strongly believes it is important to invest in, and equip, our members and affiliates with the knowledge, strategies and tools they need to be an effective advocate. For this reason, the CPA has created the Very Involved Psychologist (VIP) and Very Involved Psychological Researcher (VIPR) program. As part of that program, we have developed a toolkit to assist members in building their advocacy skill set and/or confirming their approach.

Non-Members can read more about the toolkit here – https://cpa.ca/advocacy/#Toolkit

Members can access the toolkit by signing into the CPA’s Members Only site here – https://secure.cpa.ca/apps/Pages/advocacy

Many women experience it, few have heard of it. Vulvodynia with Dr. Caroline Pukall

Vulvodynia is a condition that affects between 8-28% of all women – but it’s still a relatively unknown term. Dr. Caroline Pukall, one of Canada’s leading experts in vulvodynia, joins Mind Full to explain it to Eric and Kathryn.

Mental Health Parity Pledge (December 2021)

The Canadian Alliance on Mental Illness and Mental Health (CAMIMH) issued a press release calling on all Canadians to sign a Parity Pledge which will be sent to your Member of Parliament – which calls on the federal government to pass legislation (a Mental Health and Substance Use Health Care For All Parity Act) which will provide funding to expand access to accessible and inclusive publicly-funded mental health and substance use health care programs and services that are evidence-based. See the news conference . Please consider signing the Pledge and/or forwarding it to your colleagues, friends and family.

New Minority Federal Government (November 2021)

With a new minority government in place and a recent Speech From the Throne, the CPA has begun the process of engaging a number of relevant Ministers (i.e., Mental Health & Addictions; Health; Innovation, Science & Industry; Environment & Climate Change; Justice & Attorney-General; Indigenous Services) on a range of legislative and policy issues of importance to the CPA. As a member of the Canadian Consortium for Research (CCR), a letter was sent to the Minister of Innovation, Science & Industry.

Youth Homelessness with Charlotte Smith, Avery, and Dr. Nick Kerman

Charlotte Smith spent years as a youth experiencing homelessness on and off again. Avery has also recently experienced homelessness and abuse in the foster care system. They join Mind Full with Dr. Nick Kerman, a psychologist who has spent his career studying homelessness and housing interventions.

Melissa Tiessen And Karen Dyck of The Intentional Therapist

Dr. Melissa Tiessen and Dr. Karen Dyck created the Intentional Therapist network to help female mental health professionals (themselves included!) stay healthy and happy through intentional and playful self-care.

This is your brain on screens – i-Minds author Dr. Mari Swingle talks Instagram

Dr. Mari Swingle wrote the book ‘i-Minds: How and Why Constant Connectivity is Rewiring Our Brains and What to Do About it’. We discuss the revelations from Facebook research that shows Instagram’s negative effect on young girls, in particular – something Dr. Swingle has been writing about for years.

Science Up First Continues The Fight Against Disinformation With Dr. Krishana Sankar

Dr. Krishana Sankar returns to Mind Full to talk about the science and data around vaccines and COVID-19. Dr. Sankar and the other experts at Science Up First are continuing to combat online disinformation, which is ever-changing and doesn’t show signs of slowing down.

Pandemic Disinformation, Suicide, and Science Up First With Dr. Tyler Black

Dr. Tyler Black is a psychiatrist who specializes in suicidology. When, early in the pandemic, wild claims were being made about the spike in suicide we were sure to see as a result of lockdowns, he pushed back with his expertise in the field (spoiler alert – he was right, and suicide actually decreased). He became one of the experts at Science Up First, combatting disinformation online.

“How to Do the Work: Advocacy Skills for Psychology Students”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W7tsHuQRER0

Attaining and engaging in advocacy skills enables students to make significant contributions to society and public policy, including the ability to connect, collaborate, inspire, and work with their communities. This workshop will provide opportunities for students to gain and continually develop skills in the following key areas: leadership, advocacy, and networking.

Presented by: Joanna Collaton, Alejandra Botia, Alanna K Chu, and Glenn Brimacombe.

Originally Presented as part of the CPA’s Virtual Convention, June 22, 2021.

“Psychology Works” Resources: Training to Become a Clinical Neuropsychologist in Canada

What is Clinical Neuropsychology?

Clinical neuropsychology is a speciality within clinical psychology that focuses on understanding the relationship between brain and behaviour through research and clinical services.

Who is a clinical neuropsychologist?

A clinical neuropsychologist is a regulated health professional who uses evidence-based practice in the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of a variety of neurological, medical, and psychiatric disorders that affect cognition. Clinical neuropsychologists may also provide services to optimize cognitive functioning in healthy individuals. Subspecialties in neuropsychology include geriatric, pediatric, and forensic. There is a range of career opportunities including within hospitals, private practice, and academia; within these settings, a neuropsychologist’s work may include any combination of clinical, research, teaching, supervision, and consultation activities.

How do I become a clinical neuropsychologist?

Clinical neuropsychologists must obtain a PhD or PsyD degree to be licensed to practice clinical psychology in Canada (licensure requirements vary across provinces) and declare competency to practice within the speciality area of clinical neuropsychology.

What is the typical education path?

Typically, a bachelor’s degree in a psychology or health related field is obtained prior to completing graduate school at the doctoral level at an accredited institution that offers specialized training in clinical neuropsychology. Many universities require completion of a master’s degree prior to doctoral training.

What does graduate school in clinical neuropsychology entail?

Graduate training includes three major components: course work, research, and clinical experience.

Course work:

Course work requirements depend on the program, but topics covered generally include: human neuropsychology, neuroanatomy, neuropsychological assessment, and neurorehabilitation. Completion of these courses is in addition to the required core clinical courses of the program such as foundational courses in clinical psychology, psychodiagnostics, psychotherapeutic intervention, and statistics. Students may also take courses to specialize in an age group (e.g., child and youth or adult and older adult) or select courses across the lifespan.

Research:

Trainees must undertake major research projects (e.g., Master’s thesis, dissertation) in a topic area broadly related to brain and behaviour. As trainees are accepted into graduate programs under the supervision of a faculty member, topics are dependent on the supervisor’s research focus and can range from understanding the brain at the structural level via brain imaging to investigating the impact of a cognitive intervention in the community.

Clinical experience:

Trainees are offered a wide range of clinical experiences in clinical neuropsychological assessment and intervention across the lifespan or depending on a population of interest. Trainees are first exposed to clinical training through theory and practice in class. Under the supervision of practicing clinicians, trainees then complete clinical practica in a variety of approved settings (e.g., the clinical neuropsychology department of a hospital). Lastly, trainees complete a one-year, full-time residency in clinical neuropsychology or clinical psychology with a neuropsychology component (i.e., a major neuropsychology rotation) at an approved site (for a list of sites see https://natmatch.com/psychint/directory/participating-programs.html).

What happens after graduate school?

Graduates must complete registration examinations, and sometimes one year of supervised practice (requirement varies across provinces), in order to register with the College of Psychologists. There is also the opportunity for post-doctoral positions to gain additional training and to build research experience. Although more common in the United States, board certification for the specialization of clinical neuropsychology is available through the American Board of Clinical Neuropsychology, which is a division of the American Board of Professional Psychology.

If you would like to learn more about the experience of a current trainee in clinical neuropsychology, you can reach out to the Student Representative of the CPA Clinical Neuropsychology section (for contact information see https://cpa.ca/sections/clinicalneuropsychology/executive/).

This resource has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by Iris Yusupov, York University and the CPA’s Clinical Neuropsychology Executive Committee.

The authors wish to extend a special thank you to Drs. Jill Rich and Mary Desrocher (faculty at York University) for their review of this factsheet.

Date: October 29, 2021

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the Psychology Works Resources: factsheets@cpa.ca

Canadian Psychological Association

Tel: 613-237-2144

Toll free (in Canada): 1-888-472-0657

Reflections on Apartheid and Lessons Learned with Zuraida Dada

Zuraida Dada is a psychologist in Alberta who grew up under the apartheid system in South Africa. She was an activist despite the danger, a scholar despite the odds, and was part of the intelligentsia that rebuilt the country as it became a democracy.

The Naomi Osaka Effect: Talking elite athletes and mental health

Dr. Adrienne Leslie-Toogood and University of Manitoba psychology student (and Olympic swimming medallist) Chantal Van Landeghem discuss the mental health of elite athletes in the wake of Naomi Osaka’s withdrawal from Wimbledon.

Learning about Cognitive Dissonance and the Bystander Effect with UCalgary students

Students at the University of Calgary created podcasts for their final project in Jim Cresswell’s History of Psychology course. Listen here to learn more about Cognitive Dissonance Theory with one group, and the Bystander Effect with another.”

Dr. David Goldbloom’s new book We Can Do Better

Dr. David Goldbloom’s new book We Can Do Better: Urgent Innovations to Improve Mental Health Access and Care lays out 8 different innovations that can improve access and care right now in Canada. The CPA’s director of policy and public affairs, Glenn Brimacombe, speaks to Dr. Goldbloom about his book and the future of mental health care in this country.

“Psychology Works” Fact Sheet: Gender Dysphoria in Children

Temporarily removed, pending updates

“Psychology Works” Fact Sheet: Hire Better Job Applicants Using a Structured Job Interview

When it is time to hire a new employee, almost all organizations use some form of job interview as part of the personnel selection process. How well the interview predicts job performance depends on how well it is designed and conducted.

The typical unstructured job interview

The job interview is the most commonly used selection method available so conducting them properly is critical for successful hiring. The job interview can be thought of as an assessment, or test, like any other test used in personnel selection. The main difference is that the interview involves asking a job applicant a series of oral questions rather than completing a test online or on paper. The applicant’s responses to the interview questions are used to determine the applicant’s suitability for the job and the work environment. Interviews may serve additional purposes as well, including active recruitment of an applicant.

However, job interviews are vulnerable to a number of problems that interviewers need to be aware of if they want to conduct effective interviews, and avoid unnecessary legal risks.

Research highlights some difficulties of using the typical job interview, including:

- Potential for biased, lower ratings of applicants based on factors that are not relevant to job performance—such as appearance, gender, weight, age, or race

- Difficulty knowing which pieces of information are relevant, and why

- Judgmental biases and heuristics (ways of simplifying a complex task) often rule the day. These biases begin before the interview even starts – for example, interviewers often form initial impressions about applicants based on the resume or when meeting the applicant, and then tend to confirm these initial impressions during the interview.

Many poorly constructed job interviews suffer from questions that may vary from one interviewer to another, and that may be interpreted differently from one interviewer to another. Poorly constructed interviews may also use questions that are not actually related to the job being filled. These interviews are referred to as unstructured interviews, because the interview questions are not based on any explicit or systematic analysis of the work, questions vary haphazardly for different interviewers and interviewees, and the scoring of the interviewees’ responses is arbitrary and subjective. In essence, unstructured interviews involve the use of “gut” feelings regarding the job applicant, and the interview proceeds in a conversational format – the proverbial ‘coffee chat’. These interviews are susceptible to bias, contamination by error, inaccuracy, and weak relationships with later performance on the job. Research has shown that these kinds of interviews provide very limited information for selecting the applicant who is truly best for the job. They also offer limited legal protection for the hiring organization.

A better option: The structured job interview

Structured interviews have consistently been shown to be significantly more predictive than unstructured ones, and in fact are one of the most predictive personnel selection tools available. Structured interviews have been found to reduce or eliminate the biases discussed earlier.

Structured interviews have the following four defining characteristics.

- Question Sophistication: The development of the interview questions is guided by a “job analysis”, based on the activities performed on the job, and unique context of the work place.

- Question Consistency: All interviewers administer the same set of questions in a standardized order to each interviewee, without probing or by using a standardized probing process.

- Evaluation Standardization: A standardized scoring key is used to quantify the performance of an interviewee’s for each individual interview question.

- Limited Rapport Building: Rapport building questions and informal conversation are either prohibited or, if included at all, performed in a structured manner that is common to every job applicant and avoids asking about things prohibited by human rights legislation.

How can I build a structured job interview?

- Start with questions based on critical job requirements. Conducting a job analysis or deriving a competency model allows you to identify what knowledge, skills, and abilities are required for the job. If possible, identify critical incidents and examples of effective and less-effective behaviours of employees when facing them. Once you know what is required, then develop questions, such as those noted below, which are known to assess the job requirements in ways that are well-suited to your target applicants.

- For experienced applicants, use questions focusing on their past behaviour in related situations (i.e. behavioural questions), which are usually strong predictors of future behaviour. For example, “Tell me about a time when you disagreed with a team member. How did you react? What was the outcome?”

- For inexperienced applicants, use situational questions to determine how the interviewee would respond if presented with a particular situation, which includes some form of dilemma. For example, ”You are supervising a team of ten employees on a time-sensive project. Two team members start arguing with one another over some budgeting error, each blaming the other for the problem. One employee storms off the room yelling profanities, while the second one comes to you claiming they cannot work in this team anymore. How would you approach this situation?”

- An interview can include both types of questions listed above. Regardless of the type of question used, the same set of interview questions must be administered to all job applicants. An interview guide should seek to ensure that the interviewers understand the order in which questions should be given, the scoring key for each question, which should include definitions and/or examples of constitutes a response that merits a certain score (e.g., what is worth 4 points on a 1-5 scoring system), and so forth. Detailed instructions should be included in the interview guide and interviewer training (including training about error and biases) should be administered. Frame-of-reference training, detailed extensively elsewhere, is likely one of the best methods. Ideally, interviews should be conducted by a panel of interviews (with diverse backgrounds).

- Information obtained from the job analysis, competency model, or critical incidents should form the basis of the scoring key. For example, in order to score an interview question inquiring about levels of a given capability, such as mechanical knowledge, job experts can be asked the extent to which that capability is needed in order to effectively perform the job. (Further details on job analysis can be found in the book references.)

Where can I get more information?

CPA Industrial and Organizational Psychology Section (CSIOP)

Within the larger field of psychology, Industrial-Organizational (or I-O) Psychology is a specialty area based on the scientific study of behaviour in organizations. I-O psychologists work to improve organizational functioning and employee well-being through management and communication systems, hiring practices, performance appraisal, leadership development, and training programs.

I-O psychologists also provide professional consultation to organizations in order to help enhance work productivity and employee satisfaction. More information can be found on the section website at: https://cpa.ca/sections/industrialorganizationalpsychology/

Bridge Magazine Articles

- Society for Human Resources Management (2021). Guidelines on Interview and Employment Application Questions. Society for Human Resources Management, Inc.

Technical Guides

- Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (2018). Principles for the validation and use of personnel selection procedures (5th). SIOP Inc.

Books

- Catano, V. M., Wiesner, W. H., Hackett, R. D., & Roulin, N. (2021). Recruitment and selection in Canada (8th). TopHat/Nelson.

- Kelloway, K. E., Catano, V. M., & Day, A. L. (2011). People and work in Canada. Toronto, ON: Nelson.

- Roulin (2017). The psychology of job interviews. Routledge

Research Articles

- Chapman, D. & Zweig, D. I. (2005) Developing a nomological network for interview structure: Antecedents and consequences of the structured selection interview. Personnel Psychology, 58, 673-702.

- Latham, G.P., & Sue-Chan, C. (1999). A meta-analysis of the situational interview: An enumerative review of reasons for its validity. Canadian Psychology, 40, 56-67.

- Levashina, J., Hartwell, C. J., Morgeson, F. P., & Campion, M. A. (2014). The structured employment interview: Narrative and quantitative review of the research literature. Personnel Psychology, 67(1), 241-293.

This fact sheet has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by Drs. Thomas O’Neill, and Derek Chapman, University of Calgary, and Dr. Blake Jelley, University of Prince Edward Island. Revised by Dr. Nicolas Roulin, Saint Mary’s University

Revised: July 2021

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the Psychology Works Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

Canadian Psychological Association

Tel: 613-237-2144

Toll free (in Canada): 1-888-472-0657

Post-Federal Election Advocacy (October 2021)

As part of Mental Illness Awareness Week (MIAW, October 3-9), and the CPA’s post-election advocacy activities, the association sent a congratulatory letter to Prime Minister Trudeau noting the importance of investing in expanded and timely access to mental health care programs and services. Dr. Karen Cohen (CPA CEO) also had an Op Ed Mental Health Care in Canada: Mending the Access Gaps in The Hill Times – which is read by all Ottawa insiders – which outlines a number of recommendations to close the access gap. As well, in the capacity as Chair of Canadian Alliance on Mental Illness and Mental Health’s (CAMIMH) Public Affairs Committee, Glenn Brimacombe (CPA Director of Policy and Public Affairs) co-wrote an Op Ed on Mental Health Parity, A Time Whose Idea Has Come for The Hill Times. As the new government takes shape, CPA will continue to be active in engaging a broad cross-section of Parliamentarians.

Passing of Dr. Patrick (Pat) O’Neill

The CPA Board of Directors is sorry to announce the passing of one of its past-Presidents (2004), Dr. Patrick (Pat) O’Neill. In addition to his role as President of the CPA, Dr. O’Neill was a longstanding and impactful member of the CPA’s Committee on Ethics and remained an active and engaged member of the association until his passing. To quote Pat’s colleague, Dr. Doug Symons, “The discipline and the profession of Psychology, as well as of academia more broadly defined, are built on the contributions of exceptional leaders. Dr. Pat O’Neill was one.” The CPA extends its condolences to his family, colleagues and friends whose lives he touched and in whose memories he lives on.

The CPA Board of Directors is sorry to announce the passing of one of its past-Presidents (2004), Dr. Patrick (Pat) O’Neill. In addition to his role as President of the CPA, Dr. O’Neill was a longstanding and impactful member of the CPA’s Committee on Ethics and remained an active and engaged member of the association until his passing. To quote Pat’s colleague, Dr. Doug Symons, “The discipline and the profession of Psychology, as well as of academia more broadly defined, are built on the contributions of exceptional leaders. Dr. Pat O’Neill was one.” The CPA extends its condolences to his family, colleagues and friends whose lives he touched and in whose memories he lives on.

Spotlight: CPA Student Mentor Caryn Tong and Mentee Rohit Gupta

Rohit Gupta and Caryn Tong

Rohit Gupta

There are eight teams in the Premier Division of the Manitoba Cricket League. Each of them has an 11-person roster. Rohit Gupta, bowler for the Crescent CC, is therefore one of the 88 best cricket players in all of Manitoba. Considering he was preparing to play for his home country as a 17-year-old, it’s not a stretch to think Rohit is right near the top of the cricket player echelon in his province.

Rohit’s home country is India – population 1.4 billion. He is now in Manitoba, population 1.4 million. Rohit is a student at the University of Manitoba, just beginning the third year of his psychology undergrad. On the hottest day of the year in Winnipeg last year it was 37 degrees. That same day in Agra, India, temperatures reached 49 Celsius. On the coldest day, Winnipeg was 61 degrees colder than New Delhi.

I point out to Rohit that, of all the cities and places he could have gone in Canada, Winnipeg is likely the polar (no pun intended) opposite of India in almost every way. He says that he chose Winnipeg by design. “I was accepted to the University of Toronto, but I knew there was a large Indian community in Toronto. If I leave my country, I want to live with different people. I want to live with a wide diversity of people, so this way I can grow. Also it was cheaper to live here.”

Caryn Tong

Caryn Tong is also an immigrant, also studying psychology, and also drawn to the prairies. “My family is from Hong Kong, but we moved when I was five. So I’ve been here the vast majority of my life. I grew up in Vancouver, then I lived in Saskatoon, and I’m here in Edmonton for now.”

Caryn mentored Rohit through the CPA’s Mentorship Program – speaking to them both I can see there are more similarities than just their passion for psychology and their status as immigrants to Canada’s prairie provinces. They are both measured and precise, both have an easy and natural sense of humour, and their rapport is unforced and natural.

Rohit is a third-year student doing a Psychology Honours Degree at the University of Manitoba – “my professor sent me an email about the CPA Mentorship Program and encouraged me to apply. I thought I’d do so and see if I got a good mentor, and I did, in Caryn! She’s very nice!”

Caryn is a PhD student at the University of Alberta. She says “my classmate was involved in the CPA Mentorship Program last year, and she said it was an interesting experience. Mentoring someone who wasn’t in the same province, but someone who’s on the same journey just a little further from the goal we all have of becoming a psychologist.”

Usually, mentors help mentees with the final stages of their undergrad. Where and how to apply for a graduate program, how to navigate the system, that sort of thing. With Rohit and Caryn it is a little bit different, because Rohit was in his second year and needs assistance with other things at the moment. He says,

TAKE FOUR WITH ROHIT GUPTA AND CARYN TONG

You can listen to only one musical artist/group for the rest of your life. Who is it?

Caryn: It’s really hard to decide but maybe Lady Antebellum. I like country music, I like that the songs tell stories, and I don’t think I would get sick of that. Wait – can I change my answer to ABBA? You can dance to them, and they have stories as well. It’s ABBA.

Rohit: Arijit Singh, I would listen to him every day.

Favourite quote

Rohit: from Van Gogh: “Whatever is done in love is done well.”

Caryn: “As I have loved you, you must love one another.” – the Bible

If you could spend a day in someone else’s shoes who would it be and why?

Rohit: The prime minister of India, Narendra Modi. I want to see how things work at that national level. They always talk about so many things and they don’t do it. I just want to know why they don’t do it after committing to it. I’m curious about the factors involved in making big decisions.

Caryn: I want to see someone who’s very opposite of me, in terms of how my brain works. Like, I’m a very words-person, so I’d like to be in the brain of someone who sees more in images. Maybe some kind of artist or architect.

If you could become an expert at something outside psychology, what would it be?

Caryn: Dog behaviour. I’d love to know what goes on in their heads, and to be able to help them become the best little dogs they can be!

Rohit: Physiotherapy. I would love to work with sports people and help them to reduce their pain.

“I have questions about my writing ability, so I send my essays to Caryn to review. And she sends me back ways I can improve in this area. Last meeting we talked about what I should start doing right now to become a good psychologist in the future, so she suggested some skills I could start working on today.”

Says Caryn, “I wish that someone had told me these kind of things when I was starting out. What are the ways I could have prepared beforehand? Like, getting involved in research studies, or building and maintaining connections with professors. Rohit was already doing a lot of this stuff, but there are many logistical things you don’t think of when you apply to school.”

Both have clearly defined career goals – though Caryn says it took her a lot longer to have career path in mind than it did for Rohit.

“I liked the idea of understanding people. I’ve always done volunteer work with children and teenagers, and I realized psychology was interesting because I could understand how people think and work. I have a double major in English Literature and Psychology, but I have always thought that psychology was so practical. I enjoyed learning about how people work and interact. I have a special interest in working with trauma and cross-cultural themes. Being an immigrant myself, I know the challenges of coming into a new country where even your parents don’t really understand the culture and the changes. I’ve experienced it where the teachers don’t understand. But I’m hoping that changes, and I think it has over the last number of years, but I’m not convinced we’re there. I think that even in our profession as psychologists there’s a much greater awareness, but I still think we’ve got a long way to go.”

Rohit developed his interest for psychology and his drive to succeed in India. “My high school teacher was very passionate about psychology. When I graduated high school I came to Canada to pursue psychology. I started working with children who had autism, and that really interested me. It showed me what I wanted to do – working with children who have mental health problems. As Caryn says, it’s an emerging field, and I started this career because I have seen many people in my country who are facing mental health crises, but they don’t have the resources to support all the different problems. So right now, I’m trying to collect experiences. Working with children, working with the elderly.”

When asked if she could spend a day in the head of anyone in the world, Caryn says she is searching for her opposite; “I want to see someone who’s very opposite of me, in terms of how my brain works. Like, I’m a very words-person, so I’d like to be in the brain of someone who sees more in images. Maybe some kind of artist or architect.”

She has not found her opposite in Rohit. Rather, she has found a kindred spirit undertaking the same journey in similar circumstances as she herself did. And one who is also searching for diametrically opposed experiences to their own. Like being an elite cricket player, who moves to Winnipeg!

Conference Support

The CPA is pleased to provide 4 awards in the amount of $500.00 each to the organizers of a psychology conference that has a specific focus on undergraduate psychology students. Applications (https://cpa.ca/machform/view.php?id=32074) for funding in a given year must be received by December 1st of the previous year. Questions about this support should be sent to the attention of science@cpa.ca.

Spotlight: CPA Student Mentor Lauren Trafford and Mattia Gregory

Lauren Trafford

Lauren Trafford and Mattia Gregory have never met in person. As we speak, they are as close as they have ever come – Lauren is in a little motel in Saskatchewan, taking some time out of her journey to speak to us on Zoom. She’s in the process of traveling back across Canada from her family home in Ontario to school in Edmonton. For the first time since she began mentoring Mattia, they are actually in the same province at the same time. And yet, with COVID, they will not be meeting in person right now – and maybe not ever.

Lauren came to the CPA Mentorship Program in a very pro-active way. She started a mentorship program of her own at her school, the University of Alberta – there was a big need for peer-to-peer mentorship from people at different levels. As she began this process, she got deep into the literature about mentorship in general – how it looked in various places, how it can benefit students. When she saw the ad for the CPA Mentorship Program, it seemed like a logical next step from what she was already doing.

Mattia Gregory

Mattia, at the University of Saskatchewan, was having a lot of trouble trying to make sense of what her school’s guidance counselors were telling her. It seemed like they were throwing dozens of things at her, many of them contradictory, and she felt that the Student Mentorship program at the CPA could provide her with a little more direction. Especially for the next year, grad school, and the path forward.

TAKE FIVE WITH LAUREN TRAFFORD AND MATTIA GREGORY

You can listen to only one musical artist/group for the rest of your life. Who is it?

Lauren: Every song that comes on the radio is my favourite song! But if I have to pick one, it would be Elton John – he has a large enough catalogue that I would have variety!

Mattia: I’m like Lauren, I love every song. But I’m obsessed with the Backstreet Boys, and they’re starting to release new music, so I’m really excited.

Favourite word

Lauren: I think it’s “y’all”! I worked with a lady from Texas and I still find myself calling a group of people “y’all”!

Mattia: I don’t use the word ‘serendipity’, but I saw it as a kid and loved it – and now I have a poster and a pillow with the word on it in my room – even though I’ve never used it in real life!

Favourite quote

Mattia: “I’m not superstitious – I’m a little stitious” – Michael Scott (The Office). That’s also on a poster in my room!

Lauren: It’s ALSO a Michael Scott quote! It’s from an episode where he’s asked if he’d rather be feared or loved, and says “both! I want people to be afraid of how much they love me.”

If you could spend a day in someone else’s shoes who would it be and why?

Mattia: My older brother – he’s in med school, and the stories he tells me make me think I’d love to be present there, just to see what’s going on and what he does!

Lauren: There’s a lady named Elyn Saks whose TED Talk I just watched, and she has schizophrenia. She talked a lot about her experiences. I think that as much as we learn about these kinds of disorders, and how they manifest, I’m not really interested in the symptoms so much as I’m interested in the lived experience. So I’d be really curious to know what it’s like to live a day in her life.

If you could become an expert at something outside psychology, what would it be?

Mattia: As a kid I really wanted to be a marine biologist because I loved the ocean…so something involving the ocean…which is really broad but I’d love it!

Lauren: Cooking! I’m a terrible cook, but I would love to be a food connoisseur expert instead of a Kraft-Dinner-loving boring cook.

As we are speaking, Lauren is working with Mattia on applying to a grad school within the next couple of weeks. They connected most recently yesterday, when Lauren provided a list of schools, programs, and deadlines to simplify the process. Mattia has been looking over those options for the past 24 hours, and says “I don’t think I could ever have got here on my own”. It’s not immediately obvious for students finishing up their undergrad what the next steps entail, and where to look for that information. This is one of the reasons a mentor comes in extremely handy!

Says Lauren, “I think the value of mentorship is immeasurable, when you think about the amount of information that’s out there.”

She also says that she and Mattia ended up being a great match because their interests are so aligned. “I remember being in her position, not knowing what I was going to do. I actually ended up going to art school before I ever did psychology because I was just so confused. And even when I knew what I wanted, there was still an enormous amount of information to wade through. I feel like my experience as an undergraduate, in grad school, and even up to today has been a huge amount of Google. It’s a research mission at every step, where you don’t really have a good idea of what’s out there until you’ve been there.”

Mattia says, “Lauren’s the person I lean on when I’m overwhelmed – just letting her know that I’m having trouble with this whole COVID online thing. With my profs we can’t really talk one-on-one about how school’s going, so it’s nice to have Lauren there to let her know how I’m feeling, and it’s nice to know she feels the same way too, that I’m not the only one in this world going through this.”

It would be nice if they could lean on one another in person. But few CPA mentors and mentees actually meet during their mentorship – most are at different schools, so the mentorship tended to happen virtually even before COVID. For these two, this Zoom meeting, with some guy from the CPA, while they happen to be in the same province might be the closest they ever come to actually meeting one another. But their shared experiences, and their shared interests, and their passion for their chosen field makes it certain that they will run in the same circles for a long time to come.

2022 Pre-Budget Consultation Process (August, 2021)

Notwithstanding the calling of a federal election, CPA recently submitted its Brief to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance as part of the 2022 federal budget consultation process. The submission will have relevance with a new government being formed on September 20th.

In addition, as a member of several strategic partnerships, the CPA played a key role in the writing of other Briefs that were submitted by the Canadian Alliance on Mental Health and Mental Illness (CAMIMH), and the Canadian Consortium of Research (CCR).

“Psychology Works” Fact Sheet: Workplace Burnout

What is Burnout?

Chances are you have said or thought to yourself “I’m burned out!” at some point. In everyday life, we often use the term burnout to mean that we are “exhausted” or “wiped out” or to refer to “exhaustion of physical or emotional strength or motivation, usually as a result of prolonged stress or frustration” (Merriam-Webster Dictionary). But in psychological research, burnout refers to more than just exhaustion. The term burnout is used to describe a group of signs and symptoms that consistently occur together and are caused by chronic workplace stress. Different uses of the same word can make things hard to understand – especially since even the terms themselves vary across sources – burnt out, burned out, burnout. Adding to the confusion, the term burnout appears in The International Classification of Diseases – 11th Edition (ICD-11) but it is not classified as a disease or a medical condition. In 2019, the World Health Organization identified burnout as an “occupational phenomenon” – something due to the conditions of work.

Burnout is defined in ICD-11 as: “a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is characterized by three dimensions:

- feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion;

- increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; and

- reduced professional efficacy.

Burnout refers specifically to the work environment and should not be applied to describe experiences in other areas of life.”

Researchers have identified exhaustion, cynicism and inefficacy as three key dimensions of the burnout experience. We all feel wiped out from time to time but if you are experiencing burnout, the exhaustion is overwhelming – you feel tired almost all of the time, both physically and emotionally. You will also perceive an increased mental distance or detachment from your job, or have a lot of negative and cynical thoughts related to your job. You may feel you dislike a job you previously were passionate about – and this lower engagement itself starts to feel frustrating. It will also be harder to work – you may notice a lower sense of efficacy (ability to produce a desired or intended result) and reduced productivity, accomplishment or ability to cope with the demands of your job. Everything feels overwhelming and the effects ripple into our personal lives.

It is important to keep in mind that burnout is not just an individual problem. Burnout is the result of multiple factors from the work environment. We experience stress when the job demands we face – physical, emotional, or otherwise – are greater than the job resources we have. Think about a campfire – if there is no wood to put on the fire and it’s pouring rain – it’s going to be hard to keep that fire going.

No one wants or chooses the experience of burnout. People would prefer to be engaged and have enough resources to keep up with the demands of work and their day-to-day lives.

How do you know if you are experiencing burnout?

Burnout often has an insidious onset – meaning it gradually emerges over time.

The stage for burnout is set by workplace stress. When job demands outweigh job resources, workers experience stress. When this stress goes on for a long time, or becomes chronic workplace stress, people may experience burnout. People experiencing burnout may notice changes in thoughts, behaviour, emotions, motivation, and bodily sensations. Some signs and symptoms associated with burnout can be found below.

| Emotions & Motivations | Thoughts | Behaviour | Body/Physical |

| Loss of motivation about work; low excitement and engagement

Decreased job satisfaction Irritability, frustration, anger Anxiety, worry, insecurity Feeling alone in the world; desire to isolate oneself Feelings of incompetence and failure; drop in self-confidence

|

Negative thoughts related to one’s job

Increased focus on errors, mistakes and failures Cynicism about others’ intentions Increased mental distance or detachment from one’s job Negative or inappropriate attitudes towards clients, customers or colleagues Loss of idealism; increased intention to leave the job Difficulties with concentration, memory, judgment, decision-making |

Difficulty producing the results you want or intend at work

Lower productivity or accomplishment; inefficiency Procrastination Withdrawal and social isolation Absenteeism, Presenteeism

|

Persistent fatigue and exhaustion; feeling tired most of the time; low energy; feeling “worn out”

Pain (e.g., headaches, backaches); sore muscles Increased susceptibility to cold, flus and infections Sleep problems (e.g., difficulty falling or staying asleep, or early morning awakenings) Gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., digestive problems, ulcers); irritable bowel symptoms (e.g., abdominal pain, cramping); changes in appetite or weight Skin problems (e.g., hives, eczema) |

Workplace Burnout can be confused with some other mental health and stress related problems such as Trauma and Stress-Related disorders, Mood disorders such as Major Depression, and Anxiety Disorders. For more information on these issues, check out the related factsheets at https://cpa.ca/psychologyfactsheets/.

What causes burnout?

There are many different ideas about what causes burnout but most researchers agree that chronic work stress is a significant factor. Burnout is more likely to occur when job demands outweigh job resources.

Researchers also agree that both situational and individual factors may contribute or increase the likelihood of an individual developing burnout.

A number of risk factors for contributing to burnout have been identified:

Individual risk factors

- Demonstrating perfectionism in every aspect of one’s work, without considering priorities

- Placing too much importance on work (e.g., work as sole focus of life)

- Low self-esteem, cognitive rigidity, emotional instability and external locus of control

- Certain personal situations (e.g., major family responsibilities) disrupting work-life balance

- Difficulties in setting limits and boundaries (leading to work-life imbalance)

- Having high expectations of oneself and heightened professional conscience

- Difficulty delegating or working with a team in a stressful environment

- Inadequate adaptation strategies (dependence, poor time management, high need for support, unwise lifestyle habits, difficult interpersonal relationships)

- A highly driven, ‘A-type’ personality that is high in competitiveness and need for control

Situational risk factors

- Work overload

- Lack of control and inability to participate in decisions related to the way one’s work is done.

- Insufficient reward and recognition (e.g., financial compensation, esteem, respect) can be devaluing and heighten feelings of inefficacy.

- “Toxic” Community where work relationships are characterized by unresolved conflict, lack of psychological support, poor communication, and mistrust.

- Unfair treatment or incivility and disrespect can lead to cynicism, anger and hostility.

- Values conflicts on the job, where there is a gap between personal and organizational values, can create stress as workers must make a trade-off between their beliefs and work they have to do.

- Poorly defined responsibilities, ambiguous roles, and difficult schedules have also been identified as stressful when the situation persists.

What helps people with burnout?

The best practice approaches for burnout are multi-faceted, involving a high focus on self-care strategies for the individual, and reducing work environment stressors.

Burnout interventions should focus on both:

- the individual (e.g., increase employees’ psychological resources and enhance coping; providing rest and respite from demands; enhancing the use of self-care strategies), and

- the environment (e.g., change the occupational context and reducing sources of stress, primarily related to work demands).

There is more research on individual strategies than on environmental or organizational strategies. However, there is research evidence for the primary role of situational factors and it appears that individual-focused interventions are not sufficient to tackle severe burnout. Workplace stressors also need to be considered and addressed.

How can you prevent or deal with burnout?

For individuals

- Change work patterns (e.g., work less, take more breaks, avoid overtime)

- Develop coping skills (e.g., time management)

- Improve interpersonal effectiveness skills (e.g., assertiveness and conflict resolution skills)

- Prioritize self-care (e.g., exercise, eat healthy, get enough sleep)

- Practice relaxation, meditation and/or mindfulness strategies

- Obtain social support (from colleagues and family)

- Change the way you think about your work (e.g., using Cognitive Behaviour Therapy)

- Enhance self-understanding through psychotherapy

- Enhance emotional intelligence skills (e.g., self-awareness and self-regulation of emotions, as well as other awareness)

For organizations

- Ensure employees have a sustainable and manageable workload – where demands are realistic.

- Involve employees in decisions that affect their work tasks so they have some opportunity to exercise professional autonomy and control/ability to access the resources necessary to do an effective job.

- Recognize and reward employees for work well done.

- Build a healthy community where employees have positive relationships and social support. Develop communication and conflict resolution skills so employees have effective ways of working out disagreements.

- Develop fair and equitable organizational policies. Treat employees with appropriate respect.

- Define organizational values, job goals and expectations.

- Promote good health (including mental health) and fitness

How can psychologists help people with burnout?

Psychologists educate workplaces (leaders and employees) about burnout so they understand what it is and how to handle it, via all-team or leadership-specific workshops and professional development sessions.

Psychologists can also conduct assessments on individuals to help figure out if they are experiencing burnout and develop a plan for addressing it. Psychologists can help workplaces identify organizational factors that may be contributing to stress and burnout.

Psychologists can help you build individual skills, such as coping, stress management, time management, and emotional intelligence. Psychologists can help organizations develop programs for improving employee engagement, reducing stress, and preventing burnout.

Psychologists engage in research to help us better understand burnout and develop the best strategies for preventing and treating it.

Finally, Psychologists can advocate for people experiencing burnout.

For more information:

You can consult with a registered psychologist to find out if psychological interventions might be of help to you. Provincial, territorial and some municipal associations of psychology often maintain referral services. For the names and coordinates of provincial and territorial associations of psychology, go to https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/PTassociations/.

You can find additional information and free self-help resources on mental health in the workplace and burnout at:

- Workplace Strategies for Mental Health (workplacestrategiesformentalhealth.com)

- CSA National Standard for Psychological Health & Safety in the Workplace (https://store.csagroup.org/ccrz__CCPage?pagekey=content&contentkey=Z1003HealthandSaftey_EN)

- World Health Organization https://www.who.int/mental_health/in_the_workplace/en/

- Mental Health Commission of Canada (https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/what-we-do/workplace)

Sante mentale en milieu de travail:

- https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/Francais/ce-que-nous-faisons/sante-mentale-en-milieu-de-travail

- https://www.who.int/mental_health/in_the_workplace/fr/

- https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence//fr/

This fact sheet has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by Dr. Melanie Badali, Registered Psychologist at the North Shore Stress and Anxiety Clinic, and Dr. Joti Samra, Registered Psychologist, CEO and Founder of MyWorkPlaceHealth.

Date: May 17, 2021

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the Psychology Works Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

Canadian Psychological Association

Tel: 613-237-2144

Toll free (in Canada): 1-888-472-0657

“Psychology Works” Fact Sheet: Relationship Distress

When does relationship conflict become relationship distress?

Conflict is a normal part of being a couple. However, all of us need to feel loved, understood, and respected by the people we are close to, and conflict in these relationships can undermine our emotional security. What makes the difference is how the conflict is handled. Couples who resolve conflicts constructively strengthen their relationships over time by improving intimacy and trust. Constructive strategies include stating opinions and needs clearly and calmly listening to and attempting to understand the partner’s point of view.

Conflict becomes destructive when needs are not expressed or when they are expressed in ways that criticize, blame, or belittle the partner. For instance, a woman who is hurt that her husband plays golf every weekend may accuse him of “selfishness” instead of expressing how lonely she feels when they are apart.

Although research does not provide a “one-size-fits-all” explanation for why certain couples are more vulnerable to distress than others, the critical nature of how couples resolve conflicts and provide emotional support to one another is widely agreed upon across the literature. However, there are several areas besides how couples handle conflict that have consistent support as factors that predict distress in relationships. For instance, various personal, social, economic, and environmental determinants of health (e.g., income status, job security, health status, education level, experiences of past discrimination), can act as external stressors that may exacerbate strains in the relationships. Individual differences, such as traits like neuroticism, may also impede relationship functioning.

When a couple is distressed, typically one partner takes the position of not saying how they feel while the other partner takes the position of blaming and criticizing. This pattern, which is very common in distressed relationships, tends to get worse over time. These couples often feel trapped in fights that are never resolved. Some couples may also handle conflict through means of avoidance. Avoiding conflict still damages relationships because partners become increasingly disengaged from one another.

Finally, couples who experience ongoing conflict can become aggressive with one another, and may push, slap, or hit each other during arguments. Importantly, other destructive forms of aggression include emotional and/or verbal harms, often manifesting as non-physical and control-oriented behaviour such as cyber aggression.

The impact of conflict on individuals and families is significant. Indeed, individuals who are repeatedly involved in relationship-related conflicts are at a higher risk for a variety of mental and physical health issues, notably depression, alcohol misuse, various illnesses, and increased mortality. They get sick more easily and die earlier than happily married couples.

Distressed couples do not cope well with life’s inevitable stressors, and they may run into problems even when they go through normal changes, like the birth of a child. Children who witness repeated conflict between their parents also are at risk for emotional and behavioural problems. One of the most serious impacts of relationship conflict is divorce. The most common reason given for divorcing is infidelity, with a lack or loss of intimacy being a key driver of the infidelity. Of course, ongoing and unresolved conflict contributes to both relationship distress and loss of intimacy.

How can psychology help?

Three distinct forms of psychological treatment have been shown to help distressed couples.

Behavioural Marital Therapy (BMT) and Cognitive Behavioural Couple Therapy (CBCT) involve helping couples to communicate more effectively and to problem-solve in ways that resolve their conflicts. Emotion-Focused Couple Therapy (EFT) tackles the unmet emotional needs underlying relationship distress. Instead of trying to solve problems, the couple therapist helps the partners to talk about their needs to feel loved and important to each other in ways that promote compassion and new ways of interacting.

Clinical trials of these therapies show that the majority of couples feel more satisfied with their marriages by the end of treatment. A few studies have also shown that the gains couples made in therapy are still evident two years later, or even that the couples’ relationships continued to improve.

Unfortunately, few couples seek psychological treatment early enough. As a result, programs for relationship enrichment and the prevention of conflict have been developed. These programs focus on improving communication and teaching conflict resolution skills to couples before they are in trouble. Often, they are offered to groups over a weekend or series of weeks. Although these programs are effective in the short-term, research shows that couples often have difficulty maintaining these new skills once the program ends. ‘Discernment Counselling’, which is considered a brief intervention, may be one means of approaching these issues. Specifically, it helps couples to determine whether they wish to take steps toward divorce or to commit to working on the relationship for a set period of time.

Where do I go for more information?

- Couple relationships and cognitive-behavioural marital therapy can be found at http://www.gottman.com

- Emotion-Focused Therapy can be found at http://iceeft.com/

- Prevention and enrichment programs can be found at http://www.smartmarriages.com

You can consult with a registered psychologist to find out if psychological interventions might be of help to you. Provincial, territorial and some municipal associations of psychology often maintain referral services. For the names and coordinates of provincial and territorial associations of psychology, go to https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/ptassociations/.

This fact sheet was originally prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by Valerie E. Whiffen, Ph.D. R.Psych., Private Practice, Vancouver, BC in October 2009.

Updates: It was first updated in September 2012 and again, by the CPA’s Head Office Staff and Dr. Cheryl Harasymchuk, Ph.D., Carleton University, in June 2021

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the Psychology Works Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

Canadian Psychological Association

Tel: 613-237-2144

Toll free (in Canada): 1-888-472-0657

“Psychology Works” Resource: Preparing for an Interview

What to expect from an interview

A job interview is a social interaction between two or more individuals, (1) interviewer(s), and (2) a job applicant. Before an interview, it is likely that the interviewer and the job applicant know very little about each other. They have likely never met before, and the majority of the information would have come from the applicant’s resume, a pre-interview test results, or some initial correspondence via email or telephone.

As such, the interview process is a tool to gather additional information so both parties can make an informed decision about whether they want to continue or start an employment relationship.

For example, the interviewer is trying to assess two key “elements of fit”:

- Person-job fit: based on skills and experience, is the applicant qualified to perform the duties of the position?

- Person-organization fit: based on personality and values, will the applicant be a good fit with the company’s values, culture and preferences or interest?

At the same time, the applicant is trying to understand whether they will feel comfortable in that job/position and happy working for that organization, so they are also assessing the organization as a potential partner for this employment relationship. To promote themselves as a great place to work, the organization may highlight positive aspects about the job, the working conditions, and other organizational benefits during the interview.

During an interview, there is often some embellishment on both sides. For a job applicant, there is an incentive to put your best foot forward, which can lead to exaggeration or dishonesty about your skills or experience. In the same way, some organizations may embellish about the position, organization or benefits in order to recruit the best potential candidate.

Finally, there is a time element on all of this. There is a lot of information being shared in usually less than an hour. So there are cognitive demands on both sides to do a lot of things in a very limited amount of time.

Interviews can vary in a number of different ways, including format, interviewer(s), and medium:

Format |

|||

| Type | Brief Description | Pros | Cons |

| One-to-One | One internal interviewer from the hiring organization | Most common type of interview, making the format more predictable | Singular perspective/assessment; more potential for bias |

| Panel | Multiple interviewers from the hiring organization | More diverse perspectives/less bias, can share tasks and responsibilities among interviewers | More cognitively demanding for applicants to interact with multiple interviewers |

| Group | Multiple applicants interviewing at the same time with one or more interviewers (e.g. for large organizations) | Cheaper for the hiring organization; chance to “check” the competition for applicants | May be more stressful for the applicant; fewer opportunities to put “your best foot forward” when being assessed alongside other applicants |

| Serial | Back-to-back interviews at the same organization but with different interviewers | Opportunity to gather different perspectives for the hiring organizations. Chance to meet with more people to assess the company for the applicant | Cognitively demanding for the applicant; can be confusing as to who/what you said in each interview; requires a lot of preparation |

Interviewer(s) |

|||

| Type | Brief Description | Pros | Cons |

| Supervisors/Colleagues | Future supervisor or potential colleagues | Opportunity to highlight in-depth expertise and background (e.g. use of jargon and/or technical terms) | Not always interview experts, which can lead to interview being conducted in a very unstandardized way or introduce different types of bias |

| HR Professionals/

I/O Psychology Consultants |

External professionals with expertise in interviewing/HR processes | Expertise in how to conduct and/or design fair and appropriate interview assessments; more structured, less bias | Not experts in the job/subject matter, so language needs to be adapted (avoiding jargon and/or technical terms) |

Medium |

|||

| Type | Brief Description | Pros | Cons |

| In-person | Face-to-face meetings between interviewer and candidate | More room to clarify/expand on answers; opportunity to develop rapport and give-off a great impression using non-verbal cues | Heightened pressure/interview anxiety; difficulties with scheduling and more costly |

| Phone | Interview over the phone | May mitigate some interview anxiety; eliminates geographic distance | Less time to “sell yourself”; difficulties building rapport, zero non-verbal element |

| Synchronous Video | Live/video-conference interview | Similar to in-person, but more flexible and cheaper/easier to schedule | Risk of technical issues, poor internet connection, limited non-verbal elements |

| Asynchronous Video | Recorded video format | Most flexible option (can complete where and when you want). Very standardized and thus fair by default | Risk of technical issues, no interaction with an interviewer (so no verbal or non-verbal feedback), no opportunity to probe or follow-up |

What kinds of questions can be asked?

(1) Traditional / Popular

- Examples: “what is your main weakness?” what is your main strength? where do you see yourself in 5 years? why should we hire you?”

- Reatively easy to prepare because they are quite generic (a quick “google” to find most common questions should do the trick!)

- Can be considered as poor/sub-optimal interviewing techniques

(2) Knowledge-based

- Examples: “what is the best technique to deal with…”

- Focused on job-specific questions, such as tools, techniques, methods, concepts, etc.

- As an expert in the field, you should have the background and expertise to answer these types of questions quite easily

(3) Past-behavioural

- Example: “tell us about a time when you’ve dealt with/experienced….?”

- Based on actual behaviour – asked to reflect on what you have done in the past, ideally in a workplace or school-based context, to demonstrate whether you possess job-relevant skills or abilities

- Aims to assess if you have specific skill(s) such as leadership, communication, problem solving, time management and stress management – the question is often matched to the type of skill they are trying to assess.

- Can be considered as a “best practice” for interviewing

(4) Situational

- Example: “imagine that you are working in…?”

- Based on intentions – aims to assess similar skills as past-behavioural questions by asking how you would handle a specific, hypothethical workplace situation/issue

- May include some kind of dilemma or challenge you to decide between two or more potential alternatives to solve a problem

- Usually includes a lot of details to create a specific context, including what the problem is, what you resourcing constraints are, etc.

- Can be considered as a “best practice” for interviewing

(5) Brainteasers

- Example: “why are manhole covers round? how many ping pong balls can you put in a Boeing 747?”

- Not looking for the right answer, but instead, aims to assess your cognitive/problem-solving processing: how do you react to this weird situation where you have a bit of pressure on you? What kind of logic you do follow?

- Can be considered as poor/sub-optimal interviewing techniques

How to prepare for an interview

(1) Try to identify the “selection criteria”

- Selection criteria is what the company is looking for – what are the skills, abilities experiences qualifications that they want to assess in this interview?

How and where?

- In the job ad → Role description and required qualifications, skills, or experience

- On the company (career) website → Culture, values, etc.

- Reaching out to connections within the organization

- Using online job descriptions

- O*NET (https://www.onetonline.org/)

- NOC (https://noc.esdc.gc.ca/)

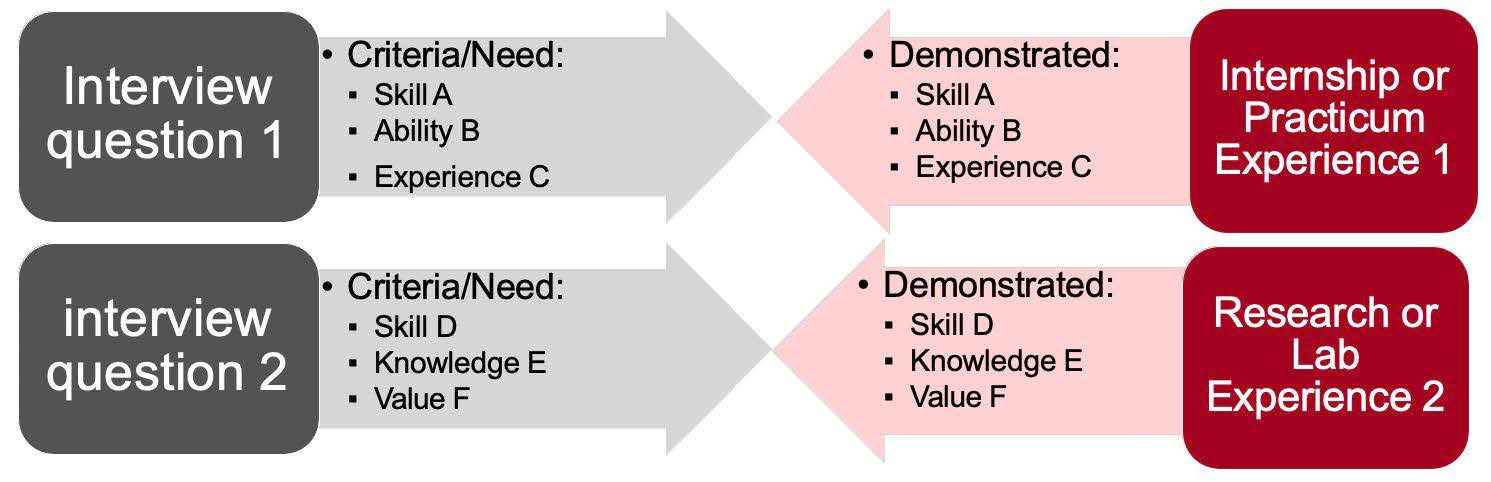

(2) Demonstrate how you can match the selection criteria

- Identify potential questions and find a relevant experience

(3) Use the STAR technique

When asked to describe a past experience or emphasize qualifications

- Situation – What was the context, when did it happen, what problem did you face?

- Task – What was your role, position, or responsibilities (e.g., leadership)?

- Action – How did you react, what action did you take, what decision did you make?

- Result – What was the result or outcome for you, your team, or your organization?

(4) Use honest impression management tactics

What does that mean?

- Present your skills, abilities, and experiences in a true but positive light

- Emphasize how your beliefs, core values, or personality align with the interviewer’s or the organization’s

- Take responsibility of your past errors or failures, but explain what happened, and describe how you learned from these experiences (e.g. providing contexting, such as COVID-19)

(5) Apply effective coping strategies to manage interview anxiety

Use…

- … emotion-oriented coping strategies (e.g., share your anxiety with others, like friends, family members, partners, colleagues)

- … or problem-oriented coping strategies (e.g., practice, use breathing techniques)

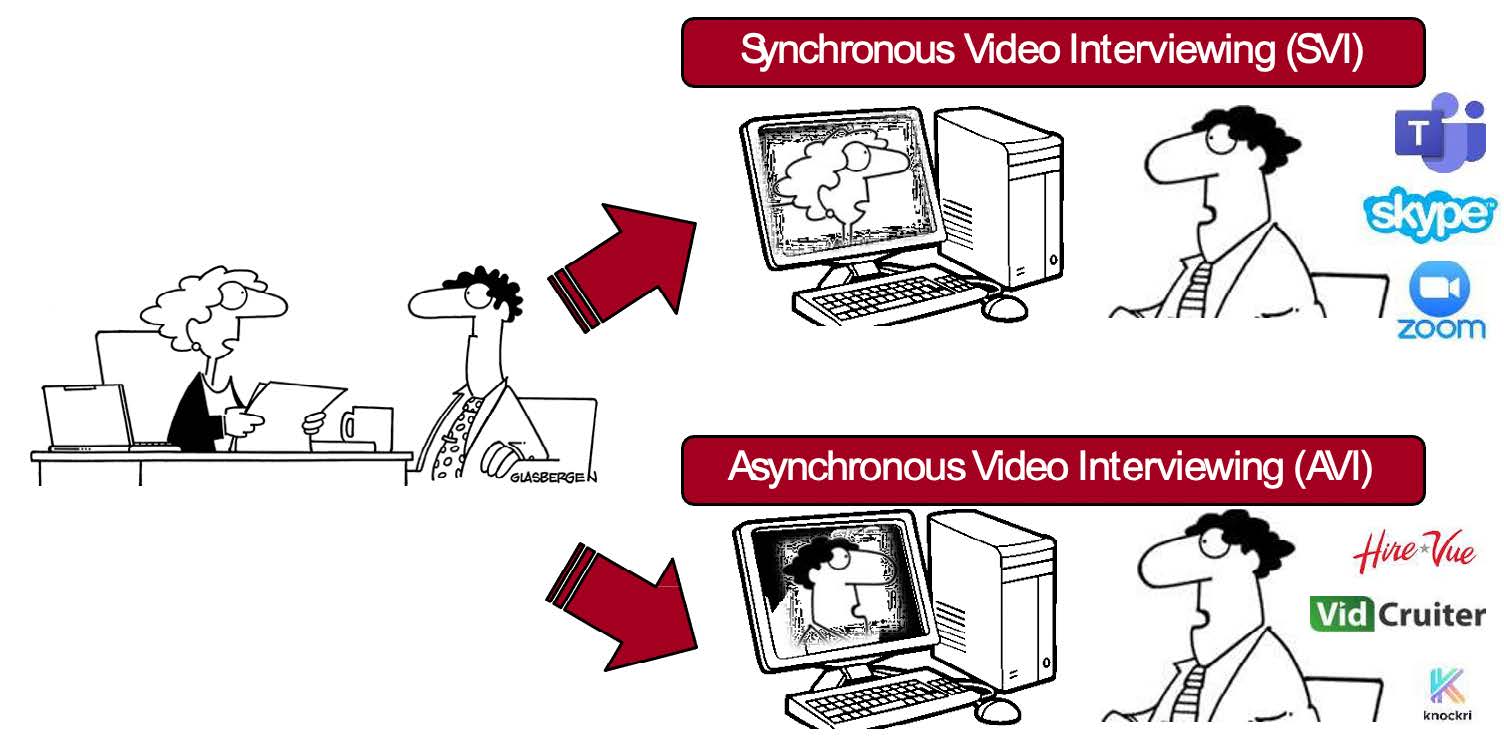

Adapting to video interviews

As more and more businesses shift to a remote or hybrid working format, a lot of interviews are moving from in-person to video or technology mediated.

Video interviews come in two key formats: (1) synchronous video interviews (SVIs) using tools (e.g. zoom, skype), or (3) asynchronous video interviews (AVIs) using a platform where you actually are invited to go online and answers questions without any live interaction, and then those answers are watched later on by an interviewer.

| SVIs | AVIs |

| • Live interaction

• Similar to in-person • Can be facing a panel of interviewers • Somewhat flexible (location) |

• Not live (recorded only)

• Talking to your camera only a largely novel experience • Multiple raters possible or automatic (AI-based) scoring • Very flexible (location + time) • Preparation or re-recording opportunities |

Tips for video interviews

- Use the same 5 tips as with traditional interviews

- But also…

- Check your tech (computer, webcam, sound/mic, internet)

- Find the right time and place (quiet, natural light, book enough time, etc.)

- Consider your background (no distraction or bias-inducing content)

- Use options available to you (preparation time, re-recording)

- Practice even more!

For more information:

More on the psychology of interviewing from Dr. Nicholas Roulin: “The Psychology of Job Interviews.” (2017). Taylor & Francis. https://www.google.ca/books/edition/The_Psychology_of_Job_Interviews/RS6EDgAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

More on video interviewing: https://theconversation.com/how-to-land-a-job-when-companies-have-shifted-to-virtual-hiring-144997

An article on virtual hiring: https://theconversation.com/how-to-land-a-job-when-companies-have-shifted-to-virtual-hiring-144997

This fact sheet has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by Dr. Nicholas Roulin, PhD, Associate Professor of I/O Psychology, Saint Mary’s University

Date: June 30, 2021.

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the Psychology Works Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

Canadian Psychological Association

Tel: 613-237-2144

Toll free (in Canada): 1-888-472-0657

Canadian Alliance on Mental Illness and Mental Health (CAMIMH) Calls for Mental Health and Substance Use Parity Act (June 2021)

The Canadian Alliance on Mental Illness and Mental Health (CAMIMH) released the discussion paper entitled From Out of the Shadows and Into the Light…Achieving Parity in Access to Care Among Mental Health, Substance Use and Physical Health. The document outlines the case for the federal government to introduce a new piece of legislation – a Mental Health and Substance Use Health Care For All Parity Act – and identifies some the elements that could be contained therein to improve access to mental health and substance use health services and supports in Canada. By releasing the report, CAMIMH hopes that it will engender a growing public policy discussion about the role of the federal government, working in close partnership with the provinces and territories, to ensure that Canadians get the care they need, when they need it.

“Psychology Works” Fact Sheet: Strategies for Supporting Social Function in Children with Epilepsy

Introduction

Students living with epilepsy can display poor social processing (e.g., reading facial cues, understanding language nuances, taking perspective), lower level of functional independence, and lower educational status which can make it difficult for them in the social realm.

They may also remove themselves from social situations to avoid having an unpredictable or embarrassing seizure in front of their peers. This worry can be significantly reduced through teacher and classroom preparedness. If everyone knows what to expect prior to a student having a seizure and how to help when a student has a seizure the collective response can be reassuring and calming. It can reduce the worry of the student with epilepsy, their parent, teacher and classmates.

Social stigma is common in epilepsy and can lead to a child having low self-esteem and a reduction in motivation to engage with school learning and activities (Elliott et al., 2005).

In an Ontario survey or parents of children with epilepsy, 69% felt that their child was not doing well socially, and 57% were worried that their child would be teased or bullied at school (ESWO, 2018).

Children who do not socialize or interact with their peers are at risk for poor outcomes as adults (Camfield et al., 2014). Often the effects of seizure activity, medication and close adult supervision will have delayed the development of independence and emotional self-control in a child with epilepsy. To meet the social-emotional competence of their peer group, children with epilepsy may need more support.

Childhood-onset seizures can impact the development of basic and complex cognitive skills that form the core foundation for long term educational, vocational and interpersonal adaptation (Smith et al., 2013).

- In some students with epilepsy, typical development milestones may have been missed and may need to be re-taught.

- Throughout development, children are learning to share and to socially interact with others. Due to their epilepsy, some children may not have acquired these important skills and may have difficulty with social interaction. They may appear self-focused and not play well with others.

- They may experience emotional or behavioural outbursts after relatively small issues because they do not have the social skills or emotional control to deal with their peers.

- They may experience severe separation anxiety when they are away from their parents and/or withdraw socially and isolate themselves from their peers.

Adult Overprotection and Restrictions at School

Students may experience reduced autonomy due to ongoing seizures and the need for greater adult supervision.

A parent or teacher may overprotect the student with epilepsy as a way to cope with the unpredictable nature of seizures. Conversely, children and youth living with epilepsy may become over-reliant on parents or teachers.

Fearing that the student is not safe or will be injured, a parent or teacher may restrict the student’s activities and remove them from social encounters, recreation and school programming (Elliott et al., 2005).

Adult monitoring and placing restrictions on age/appropriate activities suggest to the students that they are not “like other children”, that the world is a dangerous place, and that they are not capable of doing things on their own. The restrictions can cause the student with epilepsy to experience dis- continuous and fragmented learning, to feel helpless or to withdraw from social groups.

Asking parents whether their child’s health care provider has placed restrictions on activities, and if so for what, can help to ensure students engage in the activities they are capable of doing.

Strategies to support the development of autonomy and prosocial skills

- Provide opportunities that will help the student develop a sense of mastery.

- Support the development of decision-making skills and resiliency.

- Model and explicitly teach appropriate social behaviour.

- Teach alternative behaviours to achievement the student’s social goal (e.g., other ways to gain attention, other ways to create fun).

- Model ways of showing interest and respecting personal space.

- Incorporate “Social Behaviour Mapping” to support the student’s understanding of what is acceptable and how to meet the expectations.

- Encourage involvement in extracurricular activities of interest.

For More Information

You can consult with a registered psychologist to find out if psychological interventions might be of help to you. Provincial, territorial and some municipal associations of psychology often maintain referral services. For the names and coordinates of provincial and territorial associations of psychology, go to https://cpa.ca/public/whatisapsychologist/PTassociations/.

This fact sheet has been prepared for the Canadian Psychological Association by Dr. Mary Lou Smith, University of Toronto, The Hospital for Sick Children; Dr. Elizabeth N. Kerr, The Hospital for Sick Children; Ms. Mary Secco, Epilepsy Southwestern Ontario; and Dr. Karen Bax, Western University.

Revised: June 22, 2021

Your opinion matters! Please contact us with any questions or comments about any of the Psychology Works Fact Sheets: factsheets@cpa.ca

Canadian Psychological Association

Tel: 613-237-2144

Toll free (in Canada): 1-888-472-0657

References:

Camfield, P. R., & Camfield, C. S. (2014). What happens to children with epilepsy when they become adults? Some facts and opinions. Pediatric neurology, 51(1), 17-23.

Elliott, I. M., Lach, L., & Smith, ML. (2005). I just want to be normal: a qualitative study exploring how children and adolescents view the impact of intractable epilepsy on their quality of life. Epilepsy & behavior, 7(4), 664-678.

ESWO (2018). Living with Epilepsy: Voices from the Community, www.clinictocommunity.ca

Smith ML., Gallagher A, Lassonde, M. Cognitive Deficits in Children with Epilepsy. In Duchowny M, Cross H, Arzimanoglou A (Eds.). Pediatric Epilepsy, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2013, pp. 309-322.

“Psychology Works” Fact Sheet: Strategies for Supporting Optimal Psychological Function in Children with Epilepsy

Introduction

In an Ontario study of 144 parents, 111 expressed concerns about their child with epilepsy’s behaviour (ESWO, 2018).

Inattention, irritability, agitation, negativity and angry outbursts are frequent among children living with epilepsy. These issues may be primary or they may represent or mask anxiety and depression. Anxiety and depression do not necessarily present as the traditional signs of overt worrying, and changes in appetite or sleep patterns.

Feelings of irritability, anger, aggressiveness as well as anxiety and depression can occur from a few hours or a few days before a seizure occurs and then resume to a prior level after a child has a seizure. The change can be due to dysfunction in the neurons or seizures arising from the emotional control centres of the brain and/or be secondary to the consequences of living with epilepsy.

Anxiety and depression

The incidence rates of anxiety and depression among children with epilepsy are higher than in the general population, occurring in approximately a third of children living with epilepsy (Bermeo-Ovalle et al., 2016; Reilly et al., 2011; Ekinci et al., 2009).

There may be multiple causes for a child’s anxiety and depression:

Primary:

- There may be structural abnormalities in the areas of the brain related to emotion regulation and mood.