Psychology is rooted in science that seeks to understand our thoughts, feelings and actions. It is also a broad field – some psychology professionals develop and test theories through basic research; while others work to help individuals, organizations, and communities better function; still others are both researchers and practitioners.

Profiles

Psychology Month Profile: Dr. Jim Cresswell and Dr. Thomas Teo, History and Philosophy of psychology

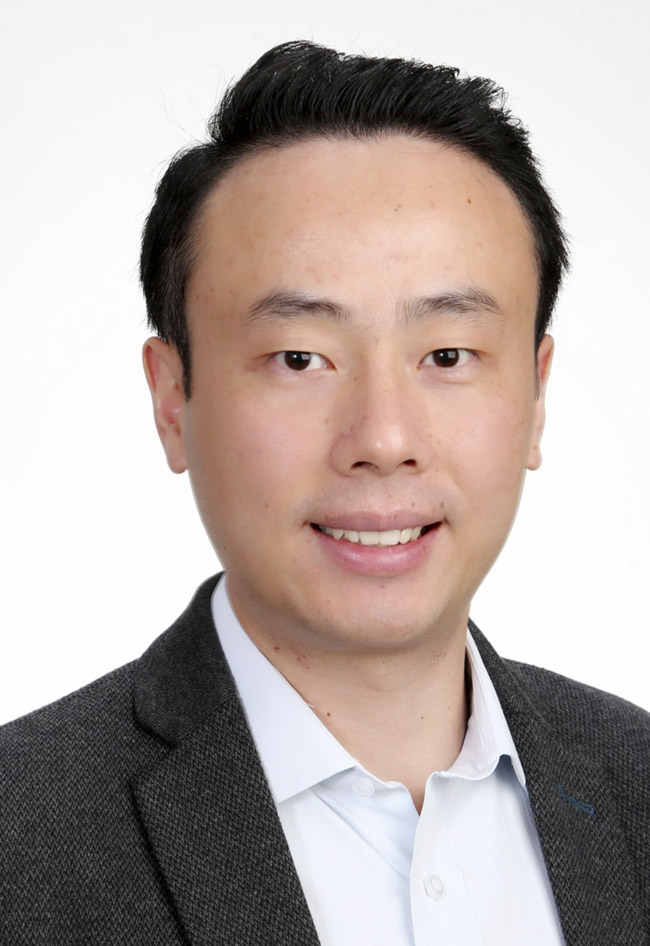

Dr. Jim Cresswell

Dr. Thomas Teo

Dr. Jim Cresswell and Dr. Thomas Teo, History and Philosophy of Psychology

The History and Philosophy of psychology is long, broad, and a truly enormous field of study. A lot of it involves ‘big-picture’ thinking. We spoke to Dr. Jim Cresswell and Dr. Thomas Teo about how they see the ‘big picture’.

History and Philosophy of Psychology

“Think about zombie movies and zombie shows – zombies are literally subhuman. You can kill a zombie, you can mistreat it completely, they don’t have any rights. In fact, you have a duty to kill a zombie because they’ll take our way of life away.”

Dr. Thomas Teo is a faculty member in the Historical Theoretical and Critical Studies of Psychology program at York University. He has been active in the advancement of theoretical, critical, and historical psychology throughout his professional career. He started out with an interest in the history of racism, worked on the relationship between psychology and racism, and on the question of the degree to which scientific psychology can be a form of violence – which Dr. Teo refers to as ‘epistemological violence’ (epistemology is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge). Recently, he has been studying the re-emergence of ‘fascist subjectivity’, based on subhumanism and racism, and the idea of cultural supremacy that we can find in the West.

“Whereas racism can be based to a certain degree on science, for instance using numbers and graphs, the notion of people being subhuman can’t be. Subhumanism - think about zombies - is strictly a visual ontology [the branch of philosophy dealing with the nature of being]. You just “see” and know what a zombie is and you don’t need a scientific explanation for that. And it is like this for some people when they see, say, migrants coming to the border. They run, the “caravan”, they walk on foot with suitcases through snow to the border, to a place where they can’t gain “regular” access. It appears to be “abnormal” behaviour, deviant from how ‘regular’ Americans or Canadians behave,. It shows visually that ‘they’ are not like ‘us’, that that are a class of subhumans. You can mistreat them, separate them from their families, throw them into cages.”

Dr. Teo suggests that, in fact, throwing them into those cages is a way to make them appear even more ‘subhuman’ to the general public. This stems from a long tradition of dehumanizing other people by portraying them as filthy, parasitic, dishevelled and desperate. Which is exactly how migrants will look after being kept in cages at the border without showers or soap or decent food, for weeks or months on end. He goes on,

“I’m basing this argument on two sources, one of whom is an American writer [Lothrop Stoddard] who wrote about the ‘underman’ which included ‘inferior races’, poor people, communists and Bolsheviks. The second source is an education manual by the SS in Nazi Germany that published a booklet with the actual title ‘Subhuman’. There was very little text; they just used pictures that contrasted human with subhumans: German versus Soviet soldiers; proper German versus Jewish mother; German versus degenerate art. It’s all visual, we can see that the ‘subhuman’ doesn’t have the characteristics of a full human being. They look to be in shambles, dirty, disorganized. It also means that anyone can become a subhuman. Not just Blacks and Jews but anyone who is an enemy of Germany – Churchill and Roosevelt were included. The concept of the ‘subhuman’ is a very malleable concept. This concept of the ‘subhuman’ does not just mean that you’re less than others, it also means there is an imperative to do something about you. If you are a parasite, a cockroach, a rat, “I” have to exterminate you or remove you.”

Dr. Teo speaks a lot about ‘subjectivity’, suggesting the field of psychology needs to focus in this area a little more in order to make sense of the enormous amount of information we have gleaned from empirical studies over the decades. For example,

“We divided subjectivity into thinking, feeling, and willing. Then we divided thinking into attention, perception, cognition and memory. Memory can be divided into short-term, long-term, episodic memory. Then you look at how one small aspect in a subdivision of a subdivision relates to another small aspect. And it’s very difficult to relate this back to the whole, to a first-person perspective (subjectivity)”

Looking at the big picture is a mantra of those who work in the area of history, theory, and philosophy of psychology. Dr. Jim Cresswell is a professor at Ambrose University, and the Chair of the CPA’s History and Philosophy Section. In addition to his work in history and theory, his areas of expertise are social and cultural psychology, and immigration and adjustment in the context of community-based research. He too talks about the necessity of looking at the bigger picture.

“Psychology as a discipline is having to grapple with post-colonialism, which means talking about subtle but ubiquitous systemic biases against marginalized people of all sorts. We don’t exactly have the cleanest track record in psychology, and a lot of that has to do with the fact that we don’t have a lot of training in thinking about what our theories mean in terms of big picture issues like systematic discrimination. We’re often focused on supporting the individual and doing empirical work in the present moment, but psychologists find themselves in a kind of cultural milieu where a focus ‘just on what the science or data say’ about the individual is not cutting it like it used to. We need to grapple with how and why our empirical efforts worked really well for certain populations, but quite badly for others.”

Although these interviews were conducted several months ago, a lot of what Dr. Cresswell and Dr. Teo said at the time resonates particularly loudly today, especially for those ‘other’ populations who are having a pretty bad time with the recent abhorrent invasion of the Ukraine by Vladimir Putin, and the fascist-style propaganda and disinformation campaigns that have accompanied it. Dr. Teo describes ‘fascist subjectivity’ this way:

“You can have fascist politics with authoritarianism and disinformation and propaganda, and so on. Fascist subjectivity is an individual dimension. If I believe that wealth should not be shared with ‘the other’, and I provide racist or sub-human arguments or feelings for that, then I am entering fascist subjectivity. It is based on the idea that wealth should exclude ‘the other’ or that wealth can be extracted from ‘the other’. In classic fascist subjectivity I can go into other countries and extract wealth from ‘these people’ because they are inferior, they are sub-human, they are parasites. They even can be exterminated if they become a burden”

The global pandemic of the past two years is another example of society’s attitude toward human life. Dr. Teo makes a distinction between those who are dehumanized to the point where extermination is no big deal, and those who are dehumanized to the point where their deaths are no big deal – though the two are clearly two sides of the same coin.

“We have ideas about ‘kill-ability’ and ‘die-ability’. In classical Nazism, Jews are killable, so are Gypsys and homosexuals and enemies, and so forth. Because they are inferior races, or sub-human, they don’t have the same status that we have and there’s no problem with killing them. Die-ability is a more interesting concept, because it moves us from a more classical fascist subjectivity to its re-emergence in our time, where it applies also to liberal democracies. We have debates in this culture, especially during the pandemic, where people say the elderly might be die-able, people with pre-existing medical conditions might be die-able, people in prison and precarious workers are die-able. People have provided economic arguments for the die-ability of many of their fellow citizens: ‘If you want to maintain your way of life, and our economy, then we have to accept that certain people will die.’

In Canada, we have seen that for a long time. Indigenous people were considered killable, and an argument could be made that in many parts of the States Black people are still understood as killable, without consequences. Currently, in liberal democracies we really need to discuss the problem and reality of die-ability, the softer version of kill-ability in a fascist subjectivity.”

That subjectivity – based on a philosophy of big-picture thinking and overarching theories that attempt to connect a variety of schools of thought to one another – is not new. Dr. Cresswell says that psychology in its early years started out with a keen focus on subjectivity, but has drifted over the past century away from this kind of big-picture thinking. Only recently has a concerted effort been made to meaningfully bring this philosophy back into psychology.

“Early psychologists, James, Hall, and Piaget – to name a few – were about 100 years ahead of their time in terms of thinking about topics such as subjectivity, research, and pluralism. Behaviourism and cognitivism that came later moved away from some of that early thinking, which was broader and more systematic. When you go back and look at some of these early writers, you find a lot that’s pertinent to the discipline of psychology’s current context.

Psychologists in the 20th century largely focused on empirical work and shifted away from the theory that underlies that empirical work. The cultural turn started in the 90s brought about a conversation concerning the possibility that our work could be ethnocentric. The result is a recent shift where we’re now starting to pay attention to the theory that informs our research and what we think our observations mean.”

Although not ‘philosophers’ by the strictest definition, both Dr. Teo and Dr. Cresswell certainly speak more philosophically than do most psychologists. As students of history, they are also students of the evolving philosophy that informs the discipline today. As with big-picture thinking, Dr. Cresswell says that philosophical thinking in the realm of psychology started more than a century ago.

“It’s probably more accurate to look at figures such as Sigmund Freud, or William James, as theorists who outlined presuppositions about how to examine the world. In contrast, consider how first- and second-year textbooks will talk about them as researchers who have been disproven in the progress of science. We tell students that they can move on past them without raising questions about what counts as science according to whom it counts. This message is a bit of a problematic stance to take. If you take cognitive theory and examine behaviourism or psychoanalysis from your cognitive paradigm, behaviourism or psychoanalysis will always be ‘disproven’. If you look at cognitive theory through a lens of behaviourism or psychoanalysis, cognitive theory will always fail. My point is that we have to teach students to deal with background paradigms that set the conditions for our empirical work. So when a textbook says we’ve moved on past this or that, they’re actually missing the fact that psychology doesn’t have a clear progressive development as a unified discipline. We actually have multiple disciplines within it and we have to recognize there are different paradigms, which means training students on how to think about history and theory.”

There has been an uptick in interest of late to go back to some of the periods where these ideas rose to prominence – particularly, the turn of the 20th century, the 1960s, and the 1990s. I know, thinking of the 1990s in terms of ‘history’ might be a little disconcerting for some. Like, Alanis Morisette released Jagged Little Pill just a few months ago, right? (It was in fact 26 years ago today that she won a Grammy for that album. She is now 47.) Dr. Cresswell says that yes, indeed the 1990s are part of history.

“Consider Wilhelm Wundt, who’s credited with structuralism and the creation of the first psychological laboratory. Half of his work was about völkerpsychologie, which is basically the ‘psychology of the community and people’. There is value in going back to such cultural theory. Another body of literature that we see in history and philosophy today is the continental critiques and philosophy. People like Foucault and the phenomenologists who partly enabled a birth of post-colonial thinking that largely happened worked outside the discipline of psychology, but there is value in understanding such theory in a milieu where we have to grapple with systematic injustice.”

The field of psychology is remembering, and learning from, its own history. Something we as a society should probably be doing a lot more as well. I’m reminded of another historic moment in pop culture, also from the 1990s – 1994, to be precise. A protest song released in memory of Johnathan Ball and Tim Parry, two men who were killed in the Warrington bombings carried out by the IRA the previous year.

“But you see, it's not me

It's not my family

In your head, in your head, they are fighting

With their tanks, and their bombs

And their bombs, and their guns

In your head, in your head they are crying”

- The Cranberries, Zombie

Dr. Veronica Hutchings

Dr. Reagan Gale

Charlene Bradford

Dr. Veronica Hutchings, Charlene Bradford, and Dr. Reagan Gale, Rural and Northern Psychology

There are unique challenges that come with living in small communities – especially those far in the north. Being a psychologist in these areas brings unique challenges as well. We spoke to Dr. Veronica Hutchings, Charlene Bradford, and Dr. Reagan Gale about their work in Yukon and Newfoundland.

“Cops probably have it really easy in a small town.

Cop: ‘can you describe who mugged you?’

Victim: ‘yeah, he was about 5’10”…’

Cop: ‘uh-huh’

Victim: ‘he was wearing a brown coat…’

Cop: ‘uh-huh’

Victim: ‘and he was…Jim.’”

I’m paraphrasing a comedy sketch I once heard by a Canadian comedian on Just For Laughs. Who it was and when the routine took place have proven to be un-Googleable! I remember thinking at the time, yeah – but it must be pretty tough on the cop too. The victim knows Jim, because he knows everyone in the town, but it must be the same for the police officer, who also knows Jim. So it is with psychologists who work in rural and northern settings

Dr. Veronica Hutchings is a Psychologist at Counselling and Psychological Services at the Grenfell Campus of Memorial University on the West Coast of Newfoundland and Labrador. She is also an Associate Professor cross-appointed to the faculties of medicine and psychology. Dr. Hutchings is currently the Chair of the Rural and Northern Psychology Section of the CPA.

“Burnout is a big thing in rural areas, when you look at the dual relationships and the boundary challenges you’re faced with in small communities. Imagine your waitlist is getting long, and you’re in a small place where people know you’re the only psychologist or maybe one of a handful. You end up with a lot of pressure – ‘can you take this person on, they’re really struggling, can you squeeze in one more?’ Dealing with that can take a toll on you. I do all my work here on the Grenfell campus, and half the stores I go to the workers are my students. I was in Halifax ten years, and in that time I think I ran into a client only twice!”

There are other challenges to providing service in rural and remote communities, one of which – especially now during the pandemic – is internet access. Ms. Charlene Bradford is a registered psychologist – registered in Alberta, operating at a private practice in Yukon. Ms. Bradford is the President of the Psychological Society of the Yukon.

“In the Yukon we definitely have internet issues, it’s a common complaint. We have really expensive internet, and in the communities more north of us it’s very spotty. You really wouldn’t want to do a lot of forms of therapy virtually because there’s going to be a lot of lag time, or the screen is going to freeze and you’ll lose someone at the wrong time. When the pandemic hit and we started to do things virtually, I was doing some training on how to provide therapy virtually and I thought – sure, that’s going to work here in Whitehorse where the internet connections can handle that, but there’s no way in the rural communities that I would trust the internet to be reliable.

We’re lucky in Yukon that we have a really amazing airline that hits quite a few of our northern communities regularly, so there’s a lot of fly-ins happening. This helps, but you also have to have clinicians who are able to travel.”

Dr. Hutchings says that some communities in Labrador have the same internet issues. Both in Newfoundland and the Yukon, some small communities closed their doors entirely so there could be no fly-in psychological services. Ms. Bradford saw small communities get hit really hard with the virus which she describes as ‘devastating’. The pandemic had already created a massive demand and very long wait times, and communities getting hit really hard by COVID only increased the need for psychological help.

The pandemic, and the small size of the communities where psychologists work in rural and northern settings, are just two of the ways psychologists operate differently than they do in urban areas. Dr. Reagan Gale is the Director of Psychology for the Government of Yukon. She is registered to practice in Alberta, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Ontario, and is currently the vice-president of the Psychological Society of the Yukon.

“I grew up in Ontario, and one thing I’ll say since coming to the north is that I’ve noticed the necessary emphasis on cultural safety and ways of knowing and ways of understanding for Indigenous people becomes even more crucial as you move north, and as you work in some of the smaller communities in other provinces where we see a greater proportion of First Nations, Inuit, and Metis people.

I do think there’s a different skill set, a different way of being flexible in helping the people we see. I’m just traveling back through Ontario from a week doing assessments in a community where food security is a profound issue, where children are consistently hungry. While I’m sure that’s the case for many in urban settings, in a small community we’re talking about a cultural norm of hunger. It’s not aberrant or an outlier, it’s the community norm that children are hungry. It calls on us as clinicians to approach practice differently.”

You may have noticed that both Ms. Bradford and Dr. Gale are ‘registered to practice in Alberta’, even though they both operate in Yukon. This is because Yukon is the only province or territory in Canada where psychologists have yet to have any kind of regulation. Says Dr. Gale,

“The Yukon is the last Canadian jurisdiction where anything goes with respect to professional psychological practice, in the absence of regulation.”

If a psychologist in the Yukon wants to be regulated (and many do) they must do so with a provincial body outside their jurisdiction. Ms. Bradford says that while this is a partial solution, it doesn’t address some fundamental issues associated with Yukon’s lack of regulation.

“We do not have a regulation college of any form in the Yukon, so many of us who are practicing as psychologists have taken it upon ourselves to regulate in another jurisdiction. It’s great, because we’re going through the regulation process, but it’s also problematic because there isn’t any regulation in the Yukon which means a few things. One, the colleges we’re regulated with have a limited ability to enforce anything outside their jurisdiction – which the Yukon is. And the other problem is that we do have people who are practicing as psychologists who are not actually regulated anywhere in Canada, and they can do that because it’s not a restricted title here.”

There are a lot of things that might happen when folks who aren’t needing to adhere to particular standards of practice can call themselves psychologists. Maybe they haven’t met the criteria to enter the profession in another territory. There are sensitive and important functions a psychologist performs, like diagnostic assessments. It’s hard to think about what process might look like for clients, many of whom are quite vulnerable, when those are performed by someone without the proper qualifications. Dr. Gale sees this often in her job.

“In my role as the Director of Psychology for the Yukon government, I’ve had people call me and ask about practice opportunities in Yukon. This is often because they’ve failed the entrance requirements to enter the profession in another jurisdiction. Maybe they’ve written the EPPP (Examination for Professional Practice in Psychology) the maximum number of allotted times and have not been able to pass, so they can’t access regulation in the jurisdiction in which they reside. I have also been approached by clinicians who have been disciplined by their regulator, and who might lose their right to practice as a ‘psychologist’ altogether. Yukon is the only spot where there is no prohibition whatsoever on that type of practice.”

So how can this be fixed? And why is the Yukon the last jurisdiction in Canada to adopt regulation? Ms. Bradford says the other two territories have a system they would like to replicate in Yukon.

“The Northwest Territories and Nunavut have an agreement with the College of Alberta Psychologists who do the regulation piece for them. We would like something like that in Yukon, and there are a lot of great reasons for it. One of the big ones being that we’re a small jurisdiction. Regulation really protects people. If things aren’t going well with your psychologist, or something seems dodgy, there’s a complaints process. With a small community you want to know that when you’re making those complaints you want to know they’re not going to your friend, your neighbour, someone you see at the grocery store [like Jim]. With a larger college it offers that protection for people in smaller jurisdictions like ours. This is the model we’re trying to go with.”

The Psychological Society of Yukon is very small, in that it consists of only twelve members – psychologists who have formed a group to collaborate and advocate for the things that are important to them. Says Dr. Gale,

“The society is committed to advocating for evidence-informed high-quality psychological services to be available to Yukoners, many of whom live in remote northern communities. I mean, Whitehorse is northern and rural for much of Canada, but we’re talking about much smaller communities than Whitehorse. The other goal is to advocate for regulation. I don’t want to speak for all twelve members of the society, but we are open to whatever path is going to be most sustainable for our Department of Community Services, which is the government branch that holds the responsibility. Speaking personally, I think we’re too small a group to self-regulate. My personal preference would be to enter into an agreement with a southern jurisdiction. But however the government can make it happen, we want to partner with them to do it.”

Ms. Bradford recalls a memorable moment in the Yukon House – yes, there are debates in the Yukon legislature that, though not well-known to the rest of Canada, can be memorable!

“The leader of the opposition was interviewing the person who’s kind of supposed to be regulating psychologists. He said ‘my understanding is that in the absence of regulation I can put up my own shingle that says Currie’s psychological services, is that correct?’ The minister in charge said ‘yes, that’s my understanding’.”

The issue of regulation is twofold. Psychologists are regulated because it creates a standard of practice, which ensures that psychologists who are providing services to people in rural and northern communities are doing so in an evidence-based way. That they will be guided by professional standards that, at the very least, try not to harm the people with whom they are working. The second benefit of regulation is that it creates a complaints mechanism, so that people who are harmed by the services provided have a recourse, and a process to follow. Regulation can’t prevent all harm, but it does provide a set of rules that minimize the potential harm. Ms. Bradford says it should be a pretty easy problem to solve.

“From our perspective, there isn’t a lot of reason why this shouldn’t go forward. Reagan did some consultation with legal representatives about what is the easiest way to move this along, and it really can be as simple as a memorandum of understanding with the College of Alberta Psychologists. Our understanding is this is simply an order in council from the government.”

And yet, it has not yet happened. Dr. Gale explains a little more.

“The barriers are the normal barriers to the government making law. It’s a small government in a small jurisdiction. The members of our society are grateful for the licensing work the government already does. This is not to criticize the important regulatory efforts that are already under way – it’s just that in such a small area, the human resource capacity to add in another profession is an ask. We think it isn’t a big ask, but any time you expand what a government is offering, it’s a political decision. We had some success lobbying during the territorial election in the spring of 2021, and all three parties made commitments toward psychological regulation, but it was the party that had the vaguest level of commitment that ended up forming the government. But we are fortunate in that both other parties are interested, and the topic of regulation is coming up in the house.”

One of the additional downstream benefits of regulation is stability. Ms. Bradford has been in the Yukon for 19 years (not all as a registered psychologist), and in that time she has seen a real change in the mental health landscape of the territory.

“People who are operating as psychologists in Yukon, who are regulated, have been here for a while. We’re invested in the community, there’s that continuity of services, and a relationship of trust that has a chance to build up over the years as people see the same person. In the past there was quite a bit of turnover, when you had people operating in some of these mental health positions who perhaps didn’t have the same level of education or knowledge in terms of being able to cope with what’s happening. They maybe didn’t have the same kind of emphasis that psychology has on self-care and avoiding burnout. So I’ve really noticed that shift as there are now more psychologists, and people are staying, turnover is reduced and services are getting stronger.”

This kind of shift to better practices, evidence-based treatment, and stability has occurred in other jurisdictions as well. Dr. Hutchings is the first psychologist ever to work in Counselling and Psychological Services at Grenfell Campus.

“Seven years ago when I came here, there was a push for my predecessor to be replaced by a psychologist because they recognized the importance of psychology. Ten years ago at this campus, there was no intake form, there was no consent process. The clinicians working there were not regulated by an official body. Now what you’re seeing is a process, an informed consent procedure, and a more structured service operating in a regulated framework.”

People in remote communities have different needs than those in small communities, although there are a lot of overlaps. For example, communities that have to have supplies flown in might struggle more with access to food, and that has a significant mental health impact. This means that for psychologists working in these areas, there is definitely no ‘one size fits all’ approach. Statisticians have argued for years of what constitutes ‘rural’ communities, and Dr. Hutchings tries to define what ‘rural’ actually means for psychologists.

“Anything that’s northern is rural, but not everything that’s rural is northern. And there are different levels of rurality of course. For example, Cornerbrook (population roughly 20,000), where I am, is kind of a central hub on the West Coast of Newfoundland. But for any major medical procedure you still have to drive eight hours to St. John’s. It’s kind of subjective, but I define rurality primarily by the size of the community, then also by how far away you are from a more ‘urbanish’ centre.”

Or, maybe put more simply – the more rural you are, the more likely you are to know Jim.

Dr. Stryker Calvez

Dr. David Danto

Dr. Stryker Calvez and Dr. David Danto, Indigenous Peoples’ Psychology

As psychology comes to grips with the need to change practices to welcome Indigenous people and attract Indigenous practitioners, the Indigenous Peoples’ Psychology Section says this will involve many important and difficult conversations. We had one with Dr. Stryker Calvez and Dr. David Danto.

Indigenous Peoples’ Psychology

“A fish is the last to discover water.”

Dr. Stryker Calvez is Michif Métis from the Red River Territory, currently living in Treaty 6 Territory in Saskatoon. He was the Manager of Indigenous Education Initiatives at the University of Saskatchewan and is now the Sr. Manager EDI Strategy and Enablement at Nutrien. Dr. Calvez is also Chair of the CPA’s Indigenous Peoples’ Psychology Section and a longstanding member of CPA/PFC Knowledge Sharing Group/Standing Committee on Reconciliation with Dr. David Danto.

Dr. David Danto is a clinical psychologist by training, and the Head of Psychology at the University of Guelph-Humber. He has been involved in a number of efforts toward Indigenizing and decolonizing psychology, institutions and universities. He is the Past Chair of the Indigenous Peoples’ Psychology section.

Eric Bollman is the Communications Specialist with the Canadian Psychological Association.

This conversation took place November 24th, 2021. Since then, 93 unmarked graves were discovered at a former residential school in Williams Lake, BC. 12 were found in Kamsack, Saskatchewan, and 42 were found in Fort Perry, Saskatchewan.

Eric: I understand there’s some talk around changing the name of the Indigenous Peoples’ Psychology section to better reflect the collaborative nature of the work – to focus more on working with Indigenous people rather than making it exclusively about Indigenous people. What sparked this discussion?

Dr. Calvez: As a group, when the new executive came together about a year ago, we realized we had a community of people who were mostly non-Indigenous. As a community of people who are interested in supporting Indigenous Peoples in Canada, we might have to change how we operate. This meant we really had to think about the mechanisms within the section. The section was originally developed to support the Indigenous psychologists in Canada, to give them a safe space and a platform to have a voice. While that is still our mandate, we also wanted to recognize that there was this growing group of people who wanted to be of service and to provide support. So in that sense we thought the name should really be reflective of this. Rather than being a section of Indigenous people, what we needed to do was work with Indigenous people, and to bring as many people as were willing to do that work together and to create a safe environment where they have everything they need, and can have courageous conversations about what has happened to them and how do you move past those places. So the name change is supposed to be a reflection of the development of a community who want to work with and for Indigenous people. And I think we’re doing that in a good way. We’ve got lots of allies – like David.

Dr. Danto: A few years ago I worked with Stryker on a response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report on behalf of the Canadian Psychological Association and Strong Minds Strong Kids (at the time known as the Psychology Foundation of Canada). What was clear from the attendees and participants in that process was that psychology has not been a great friend overall to Indigenous people historically, and even to this day in many cases. A lot of that is as a result of bringing an external Western perspective and approach to psychopathology, health, concept of the family or personality, that kind of thing, to Indigenous communities. And that’s harmful. It’s a way psychology has harmed people. It has happened in the context of education, research, and applied practice. To try to apply our ethical principles in a way that is equal to all people in this land, we have a responsibility to change those harmful practices and to use approaches that are suitable. We have to ask the question – ‘how can psychology be a good friend to Indigenous people in Canada? How can we be supportive?’ In many cases, I think the answer to that is that we can respect and acknowledge that there are already ways of healing, there’s already wisdom and knowledge that is helpful, that promote resilience and strength and well-being within the communities already. As a person who tries to be supportive in this way, I ask myself what I can do within my profession to encourage that profession to have greater respect for, and greater humility when it comes to Indigenous ways of knowing and healing. It’s not that psychology can’t or shouldn’t be involved, but we need to decentralize the approaches we use, and let the local community guide and lead what needs to be done.

Dr. Calvez: There are 1.7 million Indigenous people in Canada, and 38 million Canadians. (Re)conciliation isn’t necessarily all about Indigenous people. Although the impact of colonization has been borne primarily by Indigenous people, Murray Sinclair say that it has also harmed non-Indigenous people too. So if you think about this movement we have in psychology now, where we’re trying to get to a place where we can support the needs of Indigenous communities across Canada, there are not enough Indigenous psychologists, and not enough people with the right training to support them. So we really do need to work with allies – people who are willing to invest time getting to know and understand the needs of Indigenous communities to operate in a way that’s reflective of their expectations.

Eric: David, you mentioned ‘humility’. Is that the number one thing an ally must have when entering into this space?

Dr. Danto: Everything we learn in psychology is about ways of thinking. We talk about ‘empirical’ evidence – and the word ‘empirical’ has its root in the word ‘empeirikós’ which means known by experience. But so much of the methodology within psychology has evolved in a way to focus on what is objective and what is quantifiable objectively. That’s not a bad thing, but when we’re talking about human experience, it is an abstraction from experience. ‘Empirical’ has come to mean ‘quantitative’, and it’s not the same thing. Empirical really means within experience, and when we quantify things we’re really taking it a step away from that description of experience. That’s a very Western way of doing things. We have a respect for certain kinds of research in psychology that may not be a good fit with cultural understandings and experiences of history. So sometimes those Western approaches to knowledge get us stuck in a rut, I think, that makes us think these are the only ways of knowing that are worthwhile, testable, verifiable, and conclusive. And that means that we have lost our humility when it comes to other ways of knowing that seem to be a lower standard of knowledge. That sets us up for wanting to do only certain kinds of research within contexts where that doesn’t fit so well. When we go into communities and make use of these methods that don’t fit so well, we lose the connection with the participants in that research. Then we take our information and make use of it in our esteemed academic way, and it never comes back to the community, the community never has a chance to provide feedback because it’s not in their language. It’s not participatory or collaborative, it’s top down. And you end up with exactly the situation we have. Communities that don’t trust academics and researchers in their community, because they’re taking one more thing from the community. You know, we’ve taken land, we’ve taken rights, and now we’re taking knowledge and for who? For the sake of the university, and the researcher, not for the well-being of the community. I think humility is so important to have the approach that there’s lots of ways knowing things, and if you can take a back seat and acknowledge that your training really limits the possibilities that can be seen, rather than illuminate those possibilities – which is what those methods are supposed to be doing!

Dr. Calvez: The other element of cultural humility is that Western education and knowledge comes from a dominant position. The whole hierarchical structure of the Western world is structured in a way that one dominates another based on their education levels, or their cultural group. And that’s embedded within our paradigm of seeing the world. Cultural humility is a process through which we start to recognize that and counteract it. We need to unpack this as part of decolonization, and cultural humility gives us the tools to do that.

What might be more important than humility is commitment. This process of (re)conciliation is going to take an enormous amount of effort and it’s going to create tensions. Unless you have commitment to see things through to the conclusion of what we’re trying to do, to create a healing for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people and to the field of psychology, we can’t do that unless people are committed to go through with those intentions.

Eric: Do you ever try to recruit more people to participate in this (re)conciliation, to become allies, or are you more focused on creating a space where those allies can learn and grow alongside Indigenous people?

Dr. Calvez: An important thing about (re)conciliation is that people need to find it within themselves. The starting point isn’t knowing the issues and how to deal with them, the starting point is knowing yourself. And knowing yourself in relation to Indigenous people and the history that’s been here for thousands and thousands of years. That’s something people need to find on their own terms. Rather than promotion [reaching out to people to recruit them to become allies] it should be about attraction [creating a space where people want to become allies and reach out to you]. What we want to show people is that what we’re doing isn’t necessarily an imperative right, something that has to happen – although I do believe that’s true. What we want to show them is that this is something that’s going to benefit everybody, including our profession. There’s a good way to do this so we all learn from it, we all benefit from it. I think that’s done not by telling people you have to do it but by showing them why they might want to do it. When we get people coming on board because of their own choices, we get people who are much more capable of having the commitment I spoke to earlier, and the cultural humility.

Dr. Danto: Within the post-secondary context, I think the focus needs to be on creating the kind of post-secondary institution that’s welcoming and culturally safe and facilitates an appropriate, reflective and critical education for both non-Indigenous and Indigenous students. Rather than recruitment of Indigenous students. If you focus on asking the right questions and on being self-critical in terms of the processes that are in place, and creating that culturally welcoming safe environment, more people will be inclined to participate in what you’re doing. Indigenous people have had really negative experiences in class in the context of taking psychology courses. There are myths about genetic predispositions, assumptions and prejudices and biases because of the long history of colonization. I always use the expression ‘a fish is the last to discover water’. We are so embedded in this context of colonization, whether it’s psychology or health care or education that even with good intentions it’s very difficult for us to see. We need to do a careful examination of those spaces into which we’re inviting Indigenous people, because they may well be places where they’re exposed to re-traumatizing kinds of experiences as they’re confronted with incorrect, outdated, or unfair kinds of comments. We have a responsibility to be protective.

Dr. Calvez: When your focus is just on recruiting people in because you want more Indigenous people in your program, that’s self-serving. It’s not about Indigenous people, their needs, or what they want. If that’s your approach to supporting Indigenous people it will fail every time. We need to change the environment so Indigenous people see it as an attractive and desirable place to land. Let’s be clear – Indigenous communities have just as much need for people who are professionals in mental health as the rest of society does. We have to put the work in now, without knowing for certain that we’re going to attract those people in – just because it’s the right thing to do as a community and as a profession. I think we are moving in that direction. We’ve seen a lot of change in the last few years. That’s going to have to continue and accelerate in order to increase peoples’ interest in this work. Once they are interested, they’re going to realize that we’re not hampering anything that already exists within the profession – if anything, we’re expanding the possibilities and creating a bigger and more open space for more people to find what they’re looking for in the profession.

Eric: There have been some horrific discoveries in the past two years of mass graves at the sites of former residential schools. I think this has come as much more of a shock to white Canadians than it has to Indigenous communities who have been telling us for years that these existed. Is that true, and has it changed how you go about striving for (re)conciliation?

Dr. Calvez: I think it’s really important to recognize that when these events happen they’re really re-traumatizing to Indigenous Peoples. We’re highly affected because this is a confirmation of what we’ve been advocating for a long time. That Canadian society has not treated us right, and that they’ve actually gone to the point of harming and killing children to prove it true. That is the most horrific experience you can have as a person who comes from these communities, to know that even your children aren’t safe. I have friends who are survivors, and when this happens it sucks the wind out of you, and it takes a long time to come back to feeling like you could be okay. That’s happened multiple times this last summer alone. We knew it was bad, but I don’t thinks we knew the magnitude of it all. I very much appreciate that non-Indigenous people are having a reaction to something they didn’t know about. Having that reaction is the right thing – you probably should. But when you impose that reaction on Indigenous people to help them cope with it, that’s not necessarily the right thing to happen. We need other people to be standing up and speaking out so that we don’t necessarily have to be front and centre while we try to heal. This is where we’re moving as a profession. We should be able to advocate while recognizing you don’t go to the people who have been harmed to get support for your reaction. It’s an emerging process, and we’re new to all of this. That’s what (re)conciliation is, it’s a new idea that we’ve never seen before or had before. We’re going to have to discover it and build it from our experiences and our understanding. I think the outrage you’ve seen from both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities shows us that we’re moving in the right direction because now there’s an awareness and an appropriate response where people are extremely upset. We’re moving in the right direction in that we’re now trying to support each other in those processes. I think this is a strong time for us as a community and as a society. There are a lot of tensions we’re going to have to navigate as more revelations come forward and we experience this more and more. Most important are the conversations we’re going to have around these and other issues – and they’re going to get difficult. We need to be prepared to have those conversations both as a profession and as an individual.

Dr. Danto: My personal view is that a genocide has happened against Indigenous people in this country. Not a ‘cultural genocide’. A genocide. We are finding bodies at the sites of these residential schools, and there’s little doubt that many more remains will be found, and that no matter how many are found many more will not. As a person who is not Indigenous, recognizing that this occurred in this country – that the killing of Indigenous people in large numbers because of who they are occurred in this country. If we don’t want to admit that, we have to ask ourselves why we don’t want to. To me it is clear that is what has happened. In order to move forward, that’s part of truth. There’s a responsibility when you name something, to act on it.

Eric: Why is it that people use the term ‘cultural genocide’ when it seems quite obvious that what has happened is an actual genocide? Is it a way of minimizing the damage done, or of using a term that doesn’t require as much soul-searching of themselves, or is it something else?

Dr. Danto: The story of the residential school system in Canada was always about ‘saving’ the child while destroying the Indigenous aspect of them. Severing the cultural ties to their community and family. While that may have been the stated objective of the residential school system, and of forced adoption initiatives, much more than that was done. Many people lost their lives within that system, and within those federal government funded (and in many cases church-run) institutions, many children lost their lives. There’s no doubt about who bears responsibility for that. Calling it merely a ’cultural genocide’ is choosing to define the harms that were done in terms of their intention, rather than the outcome. We wouldn’t do that in a court of law. If your intention was to harass but not kill, and you ended up killing, you wouldn’t just get the harassment charge.

Dr. Calvez: We have to recognize that Canada as a society is just now coming to terms with what it’s done. As a stepping stone, ‘cultural genocide’ was the thing they did. They were still in this belief that residential schools could have possibly been a benefit to Indigenous children. I think that now that we’re seeing how untrue that was, people are going to come to terms with the fact that it was more than just a ‘cultural’ genocide, that it was purely genocidal. That said, I don’t dismiss the malevolence of cultural genocide itself. I am who I am because of my ancestry, my beliefs, my identity, because everything I’ve ever been is tied to the land. So to take away my world views, beliefs, and everything else, is to leave me with nothing. Although I’d physically be there I would be a stranger in my own body. It was a significant step forward to use the term cultural genocide, but we’ve now become more articulate. We’ve understood the truths that surround it, and we can call it what it really was, which is a genocide.

Eric: You’ve said that there is progress being made and that we’re moving in the right direction. Can you give me a concrete example of something that is happening now that demonstrates this?

Dr. Calvez: A large group with David and I came up with Psychology’s response to the Truth and Reconciliation Report. Since then, it has not collected dust. What has happened is that we’re seeing this invigorating conversation starting to emerge in different spots in the field of psychology. You’re seeing a change to the ethics standards. The standards are going to change, we’re increasing it and adding a value as well as a practice that will support the Indigenization of psychology and support for (re)conciliation. We’re also seeing CPAP (the Council of Professional Associations of Psychologists) and ACPRO (Association of Canadian Psychology Regulatory Organizations) step up and change the way they want regulatory boards to start addressing these issues. And David will be giving a workshop for the CCPPP (Canadian Council of Professional Psychology Programs) with Ed Sackaney on ‘Allyship, Reconciliation and the Profession of Psychology’. So even within our profession, we are now starting to see an enormous amount of change. It has just begun and the ripples are beginning to be felt across the profession.

Dr. Lindsay McCunn

Dr. John Zelenski

Dr. Lindsay McCunn and Dr. John Zelenski, Environmental Psychology

Environmental psychology has two main branches. We spoke to Dr. Lindsay McCunn about the architectural branch (designing buildings and rooms for the well-being of occupants), and to Dr. John Zelenski about the conservation branch (examining sustainable behaviours through peoples’ connectedness to nature).

“When I say I’m not judging you, I think I really mean ‘not more than other people’.”

I’m a little nervous that, during this Zoom meeting, Dr. Lindsay McCunn and Dr. John Zelenski might be judging my decidedly cluttered Zoom background. All my kitchen appliances are on a shelf behind me, giving the (accurate, it turns out) impression that my home office space is a cramped corner by the kitchen. Dr. McCunn and Dr. Zelenski are environmental psychologists, experts on the spaces we occupy and how we interact with them. Dr. Zelenski is being quite nice, and honest - we as human beings do pick up on these subtle clues based on each others’ spaces, but that is probably not unique to environmental psychologists. We all judge Zoom backgrounds, if only a little bit.

Dr. Lindsay McCunn is a Professor of psychology at Vancouver Island University. She is the Chair of the Environmental Psychology Section of the CPA and the Co-Editor in Chief of the Journal of Environmental Psychology. She says examining peoples’ Zoom backgrounds, or the way they lay out their gardens or living spaces, is a curiosity for all of us.

“The way people express themselves and set up their homes and place meaningful things around is really interesting. Sam Gosling wrote a book called Snoopology, it’s a study of how you can sort of deduce peoples’ personality and thought processes based on how they arrange their trinkets and belongings in their homes and offices.”

Dr. McCunn specializes in Environmental Psychology, and describes it this way.

“Environmental psychology is the study of the transactions between people and place. I mean a lot of different types of places – a coffee shop, an office, a school, a park, an ocean, a mountain. We study the different ways in which people interact with their settings. Much like the way a social psychologist might study and understand relationships and interactions between people and other people, environmental psychologists study and understand the relationships between people and places. In my research, I look at how people interact in communities and work environments, especially hospitals, schools, and offices. In that capacity, I look at staff, mostly, and people who use the environments in different ways than you might expect like students and patients, teachers, and so on.”

Dr. John Zelenski is a Professor at Carleton University in the department of Psychology. He is also an environmental psychologist, but he specializes in a much different area than does Dr. McCunn. One might say they represent the two major branches of environmental psychology – the architectural (Dr. McCunn) and the conservationist (Dr. Zelenski).

“In addition to being an environmental psychologist, I also think of myself as a bit of a personality psychologist and a positive psychologist. I’ve been very interested in what we call nature-relatedness, or what others call ‘connectedness to nature’. It deals with peoples’ subjective impressions – are they a part of nature, or is nature separate from them and something that has little to do with their sense of self? I’ve also been interested broadly in what I call a ‘happy path to sustainability’. That’s the idea that we know that nature is good at putting people in a good mood. Nature is associated with happiness both over long periods of time and also right there in that moment. We know that people who spend a lot of time in nature and feel very connected to it behave in more pro-environmental and sustainable ways. In the last couple of years, we’ve started thinking that maybe the reverse is true as well. That if you could get people to do a couple of nice things for nature, by engaging in some sustainable behaviours, there could be ways to use that to make them feel more connected to nature and also feel happier about these activities. The idea is that doing nice things for the environment doesn’t have to be onerous, that we might be able to link it to positive emotions.”

What ‘spending time in nature’ means to each person is subjective. Maybe it’s taking a weekend to go hiking in the hills, or spending a day ice fishing, or just going into your backyard and tending to your radish garden. For Dr. McCunn, it has meant a big shift since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. She is speaking to us via Zoom from what appears to be a cabin in the woods. She and her family lived in the downtown core of Nanaimo BC for a few years, living across the street from the ambulance service, the police service, and the fire station. Sirens increased significantly when the pandemic began, their sleep patterns began to be affected, and they decided to rent a place in the country.

“It was kind of a good case study in environmental psychology, in that we could realize what was stimulating us in our home environment, and then decide how best to alter that for our mental health. So we thought about moving to a larger natural setting where we can have a little bit more control over the things that stimulate us. We were very lucky to be able to rent something in the country. It was interesting, because I was quite attached to the house that we owned. One of the things we study as environmental psychologists is the ‘sense of place’, or a sense of place attachment/identity/dependence. At the start of the pandemic, I was hearing a lot of questions about how people could address the feelings of loss they had now that they were working from home. Not just feelings of loss in terms of social elements, but also a loss of the habitual ways in which they got to those places. Maybe they took the same bus every day, or stopped at the same coffee shop on their way to class or work. Even physicality of the office environment or the classroom itself – they were missing the setting. So I really wondered how I would react when I moved away from this familiar home environment to which I had become so attached. I didn’t want to put myself in a position of place-loss, but I quickly formed a strong attachment to this place, and the natural features around it. It has been a nice journey to explore environmental psychology from the inside out in this circumstance.”

Feeling close to nature can be as simple as being able to go outside and touch a tree, or look out your window at a mountain or a variety of bird species. So how does this translate into more pro-environmental beahaviours, when climate change has become the most pressing issue of our time? Dr. Zelenski gives an example.

“What we have is a lot of good circumstantial evidence and lab studies and we’re trying to assemble it. There have been a few programs that have been promising! My former student/friend/collaborator Lisa Nisbet has collaborated with the David Suzuki Foundation to do something called the 30 By 30 Challenge. They get people to spend 30 minutes in nature every day for 30 days. The people they get signing up for this tend to be pretty pro-environmental, and pretty connected to nature already. But over the course of this month that connectedness does seem to grow. It’s not a randomized control trial, but it seems like spending that time in nature for these folks does make them feel more connected, and along with that comes more commitment to sustainable behaviours.”

Conservation is a (relatively) new branch of environmental psychology, and has certainly become much bigger in the past twenty years, when climate change has quickly become a top-of-mind subject for so many of us. Dr. Zelenski is not alone in having moved in this direction.

“Just the attention and the amount of notice and importance the conservation side of environmental psychology is receiving seems to have really amped up in the past ten or fifteen years. I came to environmental psychology after my PhD just out of personal interest, and I feel like I’m one of a million people who are jumping on this bandwagon! It’s for a few reasons. People seem to be increasingly exhibiting symptoms of depression, anxiety, and so on – and nature seems to be a nice respite from that. Also the awareness of climate change just keeps growing and growing as we’re seeing the effects more and more. And policy-makers are interested in knowing what social science can contribute to try to solve those problems.”

The conservation branch of the discipline has naturally evolved out of the traditional architectural branch, which has been around since the 60s. Dr. McCunn says that there are a few formalized graduate programs in ‘environmental psychology’ in Canada, but there are more in England and the States, the Netherlands and South America. So when she tells people she’s an ‘environmental psychologist’, they often know what she means.

“Some people – and rightly so – split the field into the architectural psychology side and the conservation psychology side. I do that too if I’m going to clarify with people what it is I study, because I’m more on the architectural side. I work with engineers and facility managers and city planners, whereas other colleagues of mine, like John, work particularly on nature-relatedness and with people who study pro-environmental attitudes and behaviours. This idea of conservation has become very popular for the field of environmental psychology – not that it’s taken over the architectural side that deals with building infrastructure and so on. Really, environmental psychology started in this architectural realm but has very much branched out into this line of inquiry that includes asking people questions about eco-consciousness and how they relate to nature.”

The two branches do go hand-in-hand. Think of the push toward ‘green’ buildings, with energy-efficient heating, solar panels, maybe a garden on the roof. Says Dr. McCunn,

“When engineers ask me ‘should we be designing this building with sustainability in mind,’ they want to know – are people going to notice it? Care about it? And make changes in their behaviours inside (and outside) of the building because of it? I can help them study the ways in which people behave and work and function in buildings that are more (or less) sustainable. I did a study in grad school that showed that just because an office building is ‘green’ or sustainable, doesn’t necessarily mean that it will predict strong productivity or satisfaction. It’s important to be quite critical about what you expect from sustainable design and what you don’t.”

Think of some spaces you’ve been in where you felt instantly comfortable with the people around you – and others where you didn’t. It’s possible that one of the reasons wasn’t the people who were there, but the design of the space that made interaction more awkward, or made that room or building or train car feel more comfortable. Dr. McCunn explains further.

“If you want a certain space to feel homey and comfortable, you might design it for a particular number of people to be there to sit at certain distances. I’m thinking of a coffee shop design or a restaurant or even a classroom where you want people to sit in a certain way and get along in a certain way.

I think it’s important to make use of different methods, much like other psychologists do. We’re good at integrating a variety of mixed methods into our work. We use naturalistic observation to watch, and see how people are moving and behaving in a space in order to make design decisions from there. We do a lot of surveys and interviews and from these we can help architects and designers make the most humane buildings possible. If the point of clinical work, and other types of psychology, is to help people feel well, then environmental psychology is very much aligned with that. We want buildings to be designed in ways that can help people feel as healthy, motivated, enthusiastic and well as possible.”

Dr. Zelenski bridges the two sides of environmental psychology as well, in a number of different ways. Collaborations with groups who are already doing some environmental work makes it easier for him to collect data, and the analysis of that data allows those groups to be more efficient and effective in the way they operate.

“I’ve collaborated with an architect, bridging these two parts of environmental psychology. He was very interested in making buildings that make people want to behave in environmental ways. Also, maybe it’s not just the inside of the building, but what kinds of natural spaces close to the building might encourage that. This is asking a more nuanced question about what kinds of nearby nature might make people feel better, be happier, be more productive.

There’s a small non-profit that provides water testing kits. They distribute them to people and those people go out and test the nearby water quality, then they upload their data to this kind of crowd-sourced database where you can see if the lake or river near you is in good shape or bad shape, and how is it changing over time. It would be hard for me to put together an experiment where I handed out a bunch of water testing kits, but I can try to follow up with the people who are already doing this to see if it’s changing their sense of connection to nature, is it making them happy, and is it making them want to do other nice things for the environment other than just test the water?”

Since the advent of lockdowns as a result of the pandemic, we’re hearing a lot of people saying they’re appreciating nature more. It’s a safe way to get out of the house – if you can’t go to a crowded mall or a concert, you can still go to a park and walk around. People are seeing nature as a source of well-being and coping, and there have been some studies that indicate nature is one of the more positive things people have experienced during these past two years of physical distancing. But this connectedness to nature, along with the awareness of the grave threat posed by climate change, are creating new problems in some ways. Dr. Zelenski says,

“Lots of people are talking about eco-anxiety, where to the extent that people are becoming more aware of climate change it could be a double-edged sword. So it could be motivating – which is a positive outcome, people wanting to behave in a more environmental way – but for some people it might upset or worry them so much that it creates new forms of stress and concern that for some people can be maladaptive.”

One way to combat eco-anxiety, a big new buzzword on the conservation side, is an increased awareness of environmental psychologists and the seeking of their advice. This increased awareness is being felt on the architectural side of things as well, as the contributions of these experts are now seen by many as invaluable. Dr. McCunn says she’s seen this shift first-hand.

“When I come across engineers and architects and facilities planners, they’re more aware of environmental psych and are very willing to work with us. When I was doing my Master’s, I found that very few people in those positions wanted to work with a social scientist. Many said that they did that kind of research off the side of their desk, and that they ‘already knew how to study people’. Now they’re seeking me out, wanting that professional element in their business or in their processes.

Spatial cognition, for example, is very traditional topic in environmental psychology. I think it’s worth noting because the population is aging. Environmental psychologists often consult with designers about how to help people living with dementia navigate a care home, for example. We can observe them and help them with signs and symbols and ways of integrating their psychology into design to make their lives better.”

Have you ever been in a store where there is a very simple pattern on the floor that changes a little as you approach the bathroom, and a little more near the cash? Maybe there are brightly coloured hand rails along the walls, and the toilet seat is a noticeably different colour than the rest of the toilet. It’s brightly lit but not overwhelming because there are few reflective surfaces and no mirrors. A store that looks like this has probably been designed to be accessible to people with dementia, assisted by environmental psychologists.

People with Alzheimer’s Disease and dementia of different types usually work with a team of people that can include a neuroscientist (see the profile of Clinical Neuropsychology from earlier this month). Increasingly, environmental psychologists are working on larger interdisciplinary teams, and neuroscience itself is becoming a larger part of the discipline. Dr. McCunn says she is seeing this thanks to articles submitted to the Journal of Environmental Psychology.

“I see a lot of articles coming up that merge neuroscience with environmental psych. This is something I’m also doing in my own work—I’m almost finished a second Master’s in applied neuroscience just to get my research more involved in the realm of environmental neuroscience. I like trying to understand things like ‘what is happening in the brain when we feel place attachment? Is that different from when we feel attachment to a person? What’s happening in the brain when we encounter different settings?” These are important questions that I think are becoming very popular.”

As environmental psychology is becoming a discipline that is more and more in demand, the expertise of those in the field is being applied to a larger and wider variety of subjects. Dr. McCunn hopes this continues, so that the full skillset of her colleagues can be used to help solve significant problems.

“I want environmental psychology to be a part of lots of different teams. Of course architects and urban planners, but also clinicians, doctors, neuroscience teams, and so on. I think that we’re good team players and we can add facets to research questions that can complete an answer and make it more comprehensive. It’s very difficult to draw conclusions from only a few variables. Getting some big data and modeling going in environmental psych can help us help others get more reliable answers to larger questions in society about what makes people act and think in particular ways. I’d like to see environmental psychology at more tables more often.”

But rest assured – if an environmental psychologists ends up at your table, they are not going to be judging the layout of your silverware or the positioning of the gravy boat next to the jar of Nutella. At least, not more than anyone else would.

Dr. Maria Rogers

Dr. Maria Kokai

Dr. Maria Rogers and Dr. Maria Kokai, Educational and School Psychology

While the terms Educational and School Psychology are sometimes used interchangeably, they can also refer to the two parts of psychology in the education system – the researchers who come up with evidence-based best practices, and the practicing school psychologists who implement that research. Dr. Maria Rogers and Dr. Maria Kokai joined us to explain further.

Educational and School Psychology

“It’s like teaching children how to swim way before they have a chance to fall into deep water.”

Dr. Maria Kokai is a school psychologist who spent 30 years at the Toronto Catholic District School Board, the last 14 as the board’s Chief Psychologist. Now retired, she is now the chair-elect of the CPA’s Educational and School Psychology Section. Over the course of her career, she has seen a shift in the field of school psychology, as it has been moving away from a focus on assessments and dealing with children in crisis toward more of a prevention model, however this move is happening too slowly.

“COVID has really drawn attention to the importance of mental health and addressing it on a regular and consistent basis. It has also shone a light on the inequities that resulted from all the school closures and other consequences. One lesson for us and for schools I think is to make sure that mental health is addressed in a preventative way on a regular and intentional basis – as we did with anti-bullying – so that children learn coping skills, relationship skills, problem-solving. They can then apply these skills in challenging situations (which COVID has been) so they can adapt more easily with less stress.

School psychology across Canada is very different in different places. In some places we have the full range of services school psychologists are capable of providing, and in others there’s a very narrow focus on assessments and problems. What we would like to see in the profession is consistently across the board being able to provide equitable and accessible services to all students regardless of where they live, which province, a city or rural. Everybody should have access to services in an equitable way in the future. We’re not there yet.”

This focus on prevention is something school psychologists are advocating to see across all school boards across Canada. There has been significant progress in this direction over the past decade or so, but there is still a lot of work to do. Dr. Maria Rogers is a professor in the school of psychology at the University of Ottawa. She is the current Chair of the Educational and School Psychology Section at the CPA. She says,

“This really points to larger systemic issues within the field. There are not enough school psychologists, and not enough are coming out of graduate programs in Canada. There aren’t enough resources allocated toward mental health in schools. We really want to move toward a preventative mental health student success approach. There are some boards and districts that are better able (better resourced) to take a preventative approach. But many larger school districts are working under a wait-to-fail approach, which is really unfortunate. There are parallels with our health care system, where we often wait for someone to be really sick instead of taking preventative measures ahead of time.”

Some of the delays in implementing preventative programs stem from a fundamental misunderstanding in the public about what it is school psychologists do. In the minds of many, school psychology is all about testing and psychoeducational assessment. This turns out to be a rather narrow and inaccurate description of school psychology, and of what school psychologists are trained to contribute to the educational system. This idea originates from a much earlier model of school psychology work, one which arose around the mid-20th century. At that time, many schools categorized students based on their abilities and their disabilities, and they required school psychologists to participate in this classification by testing students for their eligibility for various programs. But school psychologists have a much wider range of skills and expertise. And misunderstanding or underutilizing that expertise can deprive students of a wide range of services they could otherwise be receiving. Dr. Kokai explains further.

“A lot of the public still thinks school psychologists deal primarily with students who are having problems. That’s one reason people talk a lot about assessment waitlists which are endless and a constant problem. If school psychologists had the opportunity to focus on preventative measures – mental health prevention, promotion, and early identification and intervention of potential learning and mental health problems – then those severe problems could often be prevented and there would be less need for assessments for severe problems. We advocate for a full range of school psychology services and it is for this reason – shifting the focus from strictly problems to a more preventative approach means we don’t wait for those problems to become more severe.”

Some regions have moved faster than others in focusing on student well-being, and Dr. Kokai points to one place where it is working.

“A good example is an organization called School Mental Health Ontario, which has an advisory role to the ministry of education and a resource to school boards. About a decade ago, the ministry of education in Ontario added student well-being to their goals in addition to student achievement. This meant that schools are now required to focus on student wellness and mental health and also address issues related to mental health. During that decade, a lot of progress has been made in general, and some progress in terms of using the skills of school psychologists to support the prevention and early intervention areas.”

The biggest change in school psychology in the past, say, 30 years is the narrowing of the research-to-practice gap. There has been a larger systematic effort to translate knowledge from researchers to practitioners, to make sure those psychologists and other education professionals who work with children can access research findings and apply this knowledge in evidence-based practices with kids in schools. Dr. Rogers wears both hats, as both a researcher and a practitioner.

“I do research in educational psychology as well as being a practitioner. I think that overall, the research has led us to a deeper understanding of the intersections between children’s mental health and children’s learning. At one time the two constructs would have been considered separate elements. The research has brought those disciplines together to understand how those are inseparable domains of a child’s life. What I’m seeing as well is more of a focus on researchers from around the world working together and learning from one another. We’re pooling data and resources from regions around the world to allow for larger-scale and bigger-picture investigations.”

The difference between ‘educational psychologists’ and ‘school psychologists’ is not quite as simple as the idea that ‘educational’ refers to researchers and ‘school’ refers to practitioners. Some regions in Canada and elsewhere in the world use the terms interchangeably. For the CPA’s Educational and School Psychology Section though, ‘educational – research’ and ‘school – practice’ has become a useful shorthand and is understood well by those in the field. Researchers create the science, practitioners apply it. Dr. Kokai explains,

“School psychology is applying the science of psychology in school settings. School psychologists apply knowledge and expertise in the areas of learning, mental health, behaviour and child development to help all students thrive and become the best they can be. They also connect with and support those who are most important in the children’s lives – parents, teachers, communities. It’s a very collaborative type of work in the interest of our children and youth.”

That collaboration has borne a lot of fruit over the past few decades, as practices change and focuses shift in the goal of best helping students to maintain well-being and thrive in a school setting. Dr. Rogers gives an example.

“Starting in the early 2000s, researchers started to really look at the concept of self-regulation or emotion-regulation. Some researchers started to look at it in a classroom context, and how self-regulation impacts learning. A number of researchers, and more practice-focused people like Stuart Shanker, built curriculums and supports for teachers around understanding self-regulation and how it impacts behaviour. That allowed for an improved understanding for educators.”

Psychologists and researchers have also been involved collaboratively in new methods for teaching children how to read. One of the places where a lot of this work has been done is at Sick Kids in Toronto. When Dr. Kokai was the Chief Psychologist of the Toronto Catholic District School Board, they were one of Sick Kids’ experimental sites. It was a direct link between educational practitioners and researchers. Dr. Rogers was doing her internship at Sick Kids about fifteen years ago when this new program began. She says,

“There has been a tremendous amount of attention in recent years around how we should be teaching children to read. A lot of researchers in Canada, primarily out of Sick Kids, did years of research on phonological processing and reading comprehension. They developed a program called ‘Empower’ which is an extremely rigorous and evidence-based reading remediation program. When I was doing my internship at Sick Kids about fifteen years ago, Empower was just starting to be implemented in schools in Toronto, and now it’s being used in schools across the country and teachers are being trained in the program.”

The influence of science on school psychology is just one part of this large collaborative system. Psychologists of all kinds collaborate and learn from one another. The skills imparted by a school psychologist can be useful for more than just the student. Dr. Kokai recalls assisting families in the context of helping a child.

“If you are a parent, you would use similar communication and behaviour management practices that we would maybe recommend with teachers. How to communicate, how to establish positive relationships with children, to help them become more independent and deal with peer pressure or bullies. Many of these skills very much apply to adults as well. Your relationships in your workplace, your community, and so on.”

Dr. Rogers, who works as a clinical psychologist in addition to her work at the University of Ottawa, sees the influence this kind of collaborative mindset has had on all parts of the discipline.